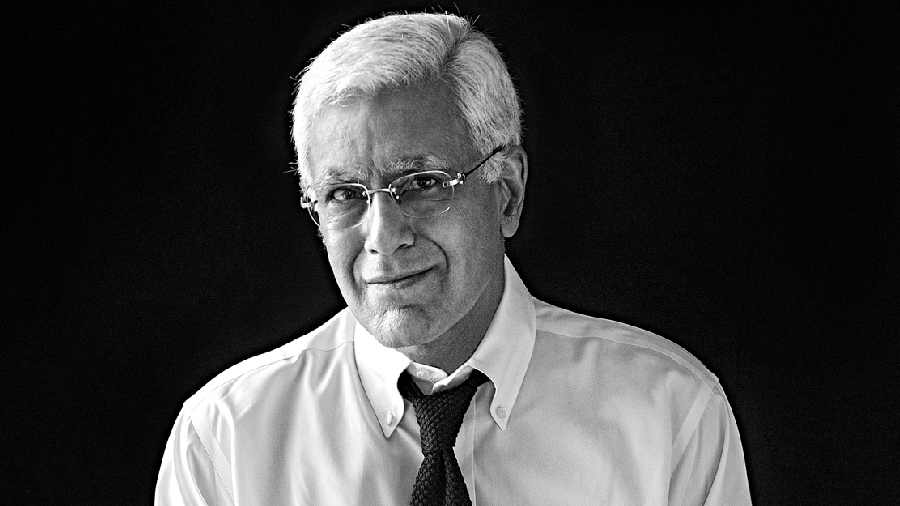

Let me begin by asking you this — it has been said that the interview, your central craft, is the lowest form of journalism. How do you react to that?

Well, that’s an opinion and everyone has a right to their opinion. I believe that the interview does three things that perhaps written journalism can’t achieve. First of all, it gives the person you are talking to, not only a chance to answer the question but to come back to whatever doubts and concerns and subsidiary questions you’ve raised. Secondly, it gives the audience the capacity to listen to not just the content of what is being said but also how it is being said, what’s the look on the person’s face, is the man or woman comfortable, and that — that unspoken element — reveals a huge amount about the person. Because often what you say can be belied by how you say it, the uncomfortable manner in which you respond. The third important thing about an interview is that you understand the person better, you can warm to their personality, or get offended and upset by their manner and style. At all three levels, the interview provides something that printed journalism often cannot.

How would you react to the impression or, indeed, the allegation that you intimidate people you interview, push and poke them? You have actually even spoken of dress codes for various kinds of interviews in Sound & Fury, your new book, almost like a Michael Korda power prescription.

I don’t intend to intimidate people. However, I won’t deny that with some that is the end result. But intimidation is a two-way process. It is a consequence of how someone is approaching you as much as a consequence of how you are responding. The second can reflect your insecurity, your uncertainty, perhaps your guilty conscience, something that you want to hide. But yes, I am persistent, at times I am firm, I try to carefully think through what I am asking and then I ask it without hesitation, and that does sometimes put people on the back foot. When you are doing an inquisitorial or interrogative interview and you know a person does not want to be pushed into corners, then firmness and assertiveness is always a help because it makes for establishing a certain authority, a certain command over the interview. However, you must never be rude and you must never lose the sympathy of the audience.

The assertiveness must happen in a way that the audience accepts that you are doing it on their behalf. The moment you lose the sympathy of the audience, the entire style becomes counterproductive. And the second thing about prescribing a certain dress code, I didn’t actually prescribe it, what I did was to tentatively suggest that there are occasions when how you dress matters. Particularly if you are young and inexperienced and lack gravitas, it helps if you dress a certain way because it gives you a sense of authority.

Following from the previous question, I wanted to know how many people would not be interviewed by Karan Thapar. I am sure you know who and why they’d turn you down.

There have been people in the past who walked out of interviews or were upset, but I was certain they’d come back. There was this interview with the late Jayalalithaa when she was chief minister of Tamil Nadu. When, at the end, I said, chief minister, it was a pleasure speaking to you, she shot up, did namaste and said it certainly wasn’t a pleasure speaking to you. But when I met her a year-and-a-half later, and this was in the presence of Naveen Patnaik, she said why haven’t you come back to interview me? I told her I thought I wasn’t your favourite person and she said, don’t be ridiculous, what a politician says to a journalist is not to be taken seriously. I take great pride in the fact that when I do a tough job and end up upsetting someone, I make sure that their hurt is assuaged because it is not my intention to personally hurt them, though it is my intention to be firm.

But all of that was before 2014 when a dramatic and radical change began to happen and which eventually manifested itself in 2017. Between 2014 and 2017, every minister in the Narendra Modi government including Arun Jaitley, Venkaiah Naidu, Nirmala Sitharaman, Piyush Goyal, all of them were readily giving interviews to me. After 2017, not only have all of them stopped giving interviews, they stopped taking phone calls, their spokespersons began boycotting me. I have been told repeatedly, whether it is by people like Ram Madhav or Prakash Javdekar, that hamein adhyakshji ne bola interview nahi dena hai. I asked what is the problem and they said even they don’t know what the problem is. I am anathema for the BJP, boycotted from top to bottom. It is like an axe had come down.

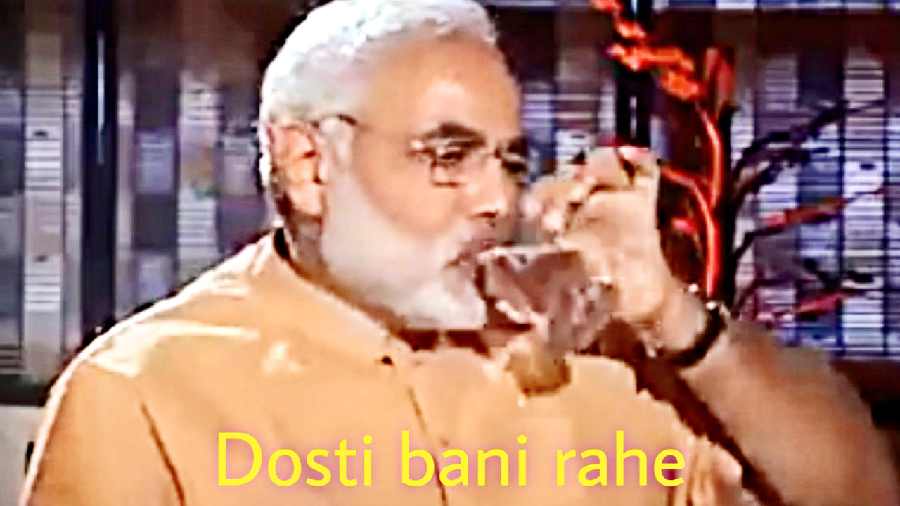

TV grab from Thapar’s 2007 ‘Dosti bani rahe’ interview of Modi File Picture

Why do you believe that happened?

It is a reaction to the fact that they are being told, or it is perceived, that I am anti-Modi, that I am hard and unsympathetic and constantly critical of him, and this is a comeback. As I mention in my book, when Modi was being tutored by Prashant Kishor for the 2014 election, Prashant played the two-and-a-half-minute clip of the interview I did with Modi when he was still chief minister of Gujarat, something like 30 times to tell Modi that he must not make a mistake like that because he will be asked the same question again and again. Modi said to him, look Prashant, after that incident, I kept Karan Thapar at home for more than an hour, fed him tea and sweets because I wanted Karan to leave my house without rancour. But, and this is the important thing, he told Prashant, I will never forgive him and will get my revenge. My subjective interpretation is that come 2017, that revenge was taken.

Did Modi actually use the word revenge?

I am saying this from memory, but I think he did. A detailed reference exists in the last chapter of my book, The Devil’s Advocate.

Who have you found the most intractable or difficult person to pin down?

It was A.R. Rahman actually. The interview was done for the BBC’s Face to Face series. He’d got the Padma Shri and he’d come straight from Rashtrapati Bhawan to our studios in Jamia. He was terribly shy. I am talking about 2000 or 2001, Rahman wasn’t used to talking about himself. So I’d ask a question and he’d go mmmm? I’d ask another question and he’d go hhmmmm? And then hmmm-hmmm. And I asked him the difference between those sounds and he said rrrhhmmmm! (laughs)

Let me rephrase that question with a narrower focus: who among politicians have you found most intractable?

It’s a difficult question to answer. Let me think. There are two kinds of people who bring up difficulties. One are those who deliberately evade, and another who tend to be very long-winded, they will go back to pre-history to answer a question about say 1860. They take up an awful lot of time with things that are utterly irrelevant and unnecessary.

You aren’t naming anyone, I want a name.

Hard to think of immediate names, I’ve been doing interviews for 30 years. L.K. Advani, I would say. These are people who are intelligent and know how to play the game. He wanted to speak, he had things to say but he’d say them in his own way. Shashi (Tharoor) is a great one to interview, but he has this going into pre-history problem, he will go to the Harappan civilisation when you are really talking of the British conquest of India. But he is engaging and has a fund of detail at his fingertips. Sitaram Yechury was fascinating to interview in the early days, one of the few people I know who welcomes tough questioning, he blossoms with it. Ram Jethmalani was fun to interview… Fun as in challenging because he was also playing games with you. There was never any question of ask this and don’t ask that, he loved the challenge.

Of the various kinds of interviews you speak of in your book — current affairs, news, celebrity — is there not a need to add a category called the predictable interview? I mean Arundhati Roy on Modi’s India. Everybody knows what she’s going to say. Or Ram Guha on Modi courting cameras at the Ahmedabad cricket game. It’s foregone what Ram is going to say.

That’s a way of looking at it, I don’t deny it but let’s take Ram Guha as an example and build up a case around him. I usually interview Ram after he has written an insightful article for your paper. Your paper is, unfortunately, mainly sold and read in Calcutta, so there is a huge, huge India outside of the readership of The Telegraph which needs to have access to Ram’s views. Often Ram himself draws my attention to some of his pieces. So, yes, I use his writing for your excellent paper as the spine of a conversation but we try to take those ideas further, and the reason I do it is that Ram’s insights or critique or reading of a situation ought to be more widely known.

Have you stopped pursuing the Modi ecosystem or are you still pursuing them?

I have not written to the Prime Minister for over a year or two. The last time I would have been bombarding him with interview requests would have been in the run-up to 2019 and I was completely ignored. Nobody from that world will speak to me. By the way, Sonia Gandhi promised me an interview and every time I remind her of her promise, she says, but I didn’t say when. I asked Rahul Gandhi way back when he first became an MP and he said, give me a year and I shall talk to you. It has been 16-17 years and I am still to hear from him.

Would you say that the short clip in which Modi took sips of water and eventually walked out saying dosti bani rahe is the most enduring piece of footage that has come from you?

Probably. It got a life of its own. It lasted for about two minutes and 40 seconds and then he left saying dosti bani rahe. The interesting thing is, when it was broadcast the next day, he rang me and said, Karan tumne merey kandhe pe bandook rakh ke goli mari (you fired a shot from my shoulder). And I told him, Modi saheb maine aapko kal hi kaha thha that if you leave me with a two-and-a-half minute clip it will become a news item which will go on every single bulletin but if you give me an interview it will be shown once or twice and be forgotten. But he didn’t listen to me. Anyhow, his last words to me in that call were: “I love you brother, jab Dilli aayenge to hum aur tum bhojan karenge.” I don’t know about the love, but the bhojan hasn’t happened and it has been nine years.