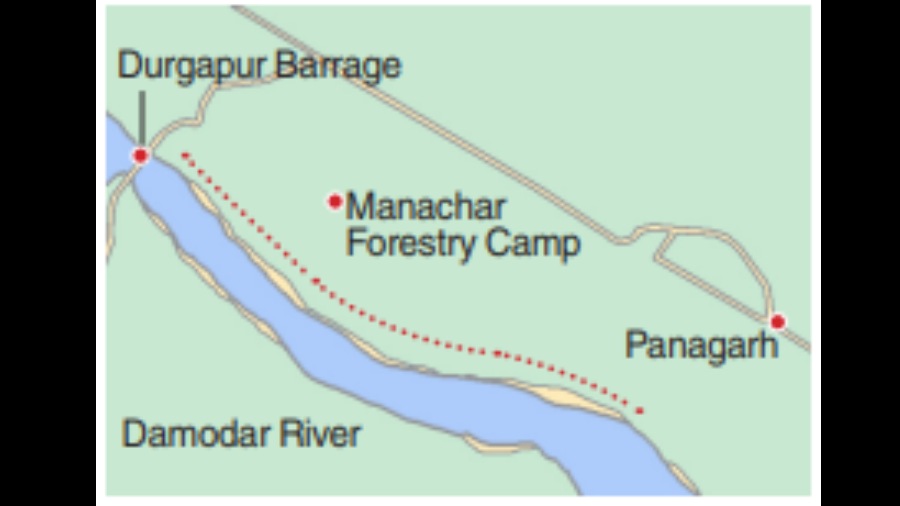

Once upon a time, when my forefathers were looking for land to settle down, they found this barren sandbar and decided to make it a habitable place,” says Nani Roy, 42, a resident of Manachar. Char is the Bengali word for sandbar. Manachar is the sandbar that extends from Durgapur Barrage to Panagarh in Burdwan district. About three kilometres in breadth and 18 kilometres in length, it is in the basin of the Damodar river. “That was way back in 1949-50,” Roy adds.

Today, Manachar is a full-fledged village of 35,000 people; 10,500 of them have voting rights. Administratively in Bankura district, it shares a border with Burdwan.

The Congress-led Bengal government had given pattas or deeds to these people in 1969-70. In 1990, says Roy, the Left Front government cancelled these deeds, started a designated department for rehabilitation of the refugees, which in turn issued fresh deeds. According to these deeds, Manachar residents were given nine bighas (one bigha equals 0.62 acres) of agricultural land and one bigha to build a house on. It was stipulated that this land could not be sold for the next 10 years, after which the deeds would have to be registered.

“Thirty-two years have passed, but our deeds have not been registered. We cannot avail of central schemes such as Kisan Credit Card and Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana and state schemes such as Krishak Bandhu and West Bengal Farmers’ Old Age Pension,” says Roy, who used to work in a private company in Calcutta.

In the meantime, illegal sand mining became rampant in Manachar. “Small trucks started coming in from 2010-2011 and carried away sand from the riverbed. But in 2012, it became a big affair,” says Roy. Boring machines fixed onto boats started digging deeper. The locals went to the police, but the mining continued.

Kunal Deb, who is an environmental activist, says, “Thousands of trucks move in and out of Birbhum daily, loaded with sand stolen from the sandbars of rivers Mayurakshi, Kopai, Ajay, Bakreshwar, Dwarka — all in Birbhum district.” Deb works largely in the Malharpur area of Birbhum district. He talks about rivulets and distributaries that have turned as narrow as drains because of indiscriminate sand mining activities.

He says, “When machines are used to mine sand, it creates deep wells in the middle of the sandbars. These are dangerous. When floods or flash floods happen, people get trapped in them and die. These obstruct the free flow of the river as well, because of which the alluvial soil does not settle down. After a flood, it becomes a sandy, infertile tract of land.”

The people of Manachar took a stand. “We protested. We undertook a fast,” says Roy. This was in 2017. It had taken five years for them to find a leadership under whom they could consolidate and voice a united protest. “When Nani (Roy) came back from Calcutta, the village elders asked him to do something. He was educated and he had the courage to speak to the mafia,” says Krishnapada Barui, 62. Barui lets on that Roy has received death threats from the sand mafia.

Roy says, “The men responded to our call later, the women came first.” Sankari Sarkar, 60, got together all the women and they went on a fast with Roy. Says Sarkar, “In 2011, we protested. Nani was not around. One of our boys was attacked with an axe and we were beaten up. The police registered complaints against us. We then went to meet Mamata Banerjee. It was after she and Abhishek Banerjee spoke to the police in Durgapur and Bankura that we could return home. Nani united us when he came back in 2012.”

The incident was widely reported and the state government was forced to take note. After four days of fasting, block-level officers came to meet the people. Says Roy, “The then TMC MLA Soumitra Khan (now with the BJP) had also come but we drove him out. He had said he wasn’t aware Manachar was part of his constituency and that it was home to so many people.”

Roy and the villagers raised seven demands — close all sand mining ghats around Manachar; build roads, a high school and a hospital; create a gram panchayat; build a cold storage unit; and provide jobs to women. “None of the demands have been fulfilled to date other than two — the closing of the mining ghats and construction of roads,” says Roy

But after the 2017 protest, 23 people were arrested for illegal sand mining. The boring machine was dismantled and removed, says Barui.

The red dotted line indicates the stretch of Manachar Map by Manoj Roy

“We were not landless and homeless people when we came from East Pakistan,” says Sunil Sarkar, 72. He recalls how all day long they would clear weeds and mana gaachh (weeds) and prepare the land for agriculture. He adds, “It was heartwrenching to see how they would make holes here and there and make that same land uncultivable.”

Manachar still has enough and more fertile alluvial soil wherein residents grow all kinds of vegetables. Says Roy, “During the potato growing season, we sell 25 lakh sacks of potatoes (one sack weighs 50 kilos). We grow groundnuts worth Rs 30 crore at the very least.” Manachar has 500-600 bighas under flower cultivation alone.

And what about the registration of deeds? Roy tells The Telegraph that the high court has ordered the Bengal government to finish the registration process by May 2022. “But we are still waiting,” he says.