In 2001, a few days before the devastating earthquake jolted the state, I was travelling all over Gujarat from one village to another, most of the time in rickety buses. As in most private buses all over the country, pictures of deities were hanging on the wall of the enclosure behind which the driver sat. One of the pictures was rather curious, as it depicted a woman, obviously a goddess, confidently astride a crocodile. Who could she be? She was certainly not Ganga, because her mount is the mythical makara, and this was definitely a crocodile. I had asked some anthropologist friends about her identity, but they were of no help.

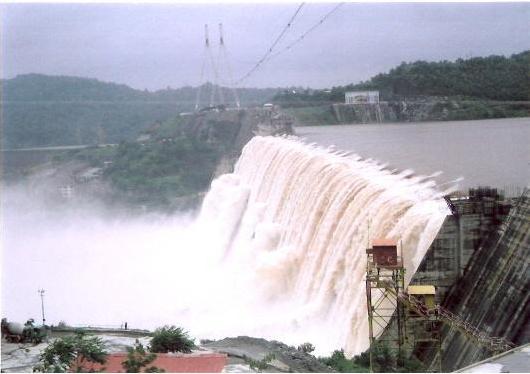

It took me 17 long years to put myself wise to the goddess and the crocodile. Last month I was in Mandla, which is a small and quite unremarkable town in Madhya Pradesh, a two-and-a-half-hour drive from Jabalpur. The swift but muddy Narmada flows through it all the way from its source in the higher reaches of the Amarkantak hills. A few kilometres away from the town, the river forks out into several torrential streams that leap down a bed of dark rocks and boulders, the boiling waters churning and frothing noisily, sending up millions of droplets that create a fine mist above it. It is called Sahashtradhara, and in the midst of the river is a white, rather squat ancient temple of Shiva. It is not as spectacular as the Dhuandhar falls in Jabalpur where the Narmada wends its way through the magnificent Marble Rocks, but Sahashtradhara's beauty is certainly not to be sniffed at. The river flows through Gujarat as well, where the Sardar Sarovar dam was erected, the one that had triggered movements against it as it was feared that it could have calamitous effects on the local environment.

Inside Mandla town and close to the bridge that spans the river is a series of ghats, the most crowded of which is Rapta ghat, surrounded by temples and the shaded steps that lead down to the river. In the evenings, aarti is performed on the ghat, and occasionally sacred verses are sung on the steps. It is hardly as theatrical as the aarti on the ghats of Varanasi, but the dark river, the flickering lamps and the music together create a rather pleasant ambience. Both day and evening, hundreds of people gather at the ghat to offer prayers and puja to Narmada ji, as they call her.

Placards with messages and likenesses of gods and goddesses are hung near the ghat, and one of them depicts the eponymous goddess, a blow-up of its calendar art avatar that I had spied in a Gujarat bus. It is known that crocodiles infest some stretches of the river, and often attack human beings who bathe in the waters or do not take the reptiles seriously enough when answering the call of nature. Little wonder that the river goddess is depicted sitting calmly on a crocodile. How close are myths and legends to our ground realities! The bejewelled lady in a sari smiles benignly, although the river in Mandla hardly looked tame when the monsoon rain lashed this settlement, so close to the Satpura range.

Narmada, also known as Rewa, has a lineage as exalted as that of any other divinity in the Hindu pantheon, for she is said to have sprung from the body of Lord Shiva and is considered to be one of the seven holy rivers. Hence, pilgrims and sadhus follow her course - some on foot - from Amarkantak to Bharuch and back again along the opposite bank. Such is her sanctity, second only to the Ganga.