****

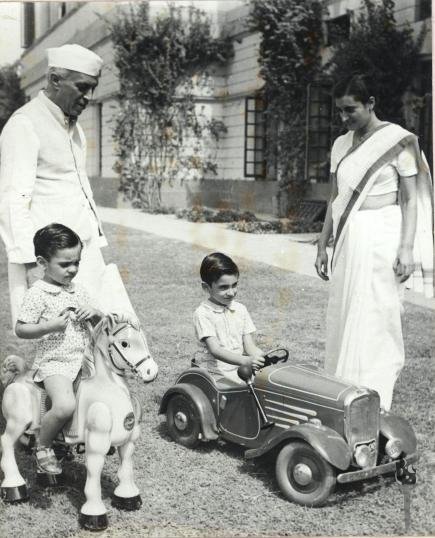

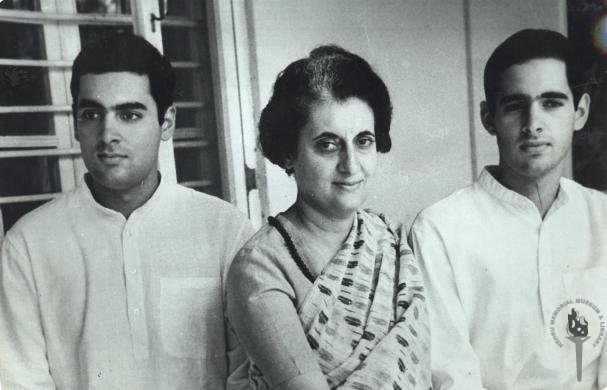

About her other, older son, Rajiv, she used to say, ‘He doesn’t know anything about politics.’

It must have been a very bleak time for Indira Gandhi and both sons when the Congress lost the 1977 elections. Rajiv and his Italian-born wife, Sonia, were so disgusted by all that had happened in the run up to 1977 that they were considering packing their bags to go and settle in Italy.

At that point neither Indira Gandhi nor Sanjay and their followers in the Congress could have predicted they would come back with an overwhelming majority in 1980. But the coalition government headed by Morarji Desai made a mess of things with endless squabbles between Morarji and Charan Singh, then the home minister.

What the public wanted was a government that stood for stability and decisiveness and Indira Gandhi with all her faults was judged to be a better option.

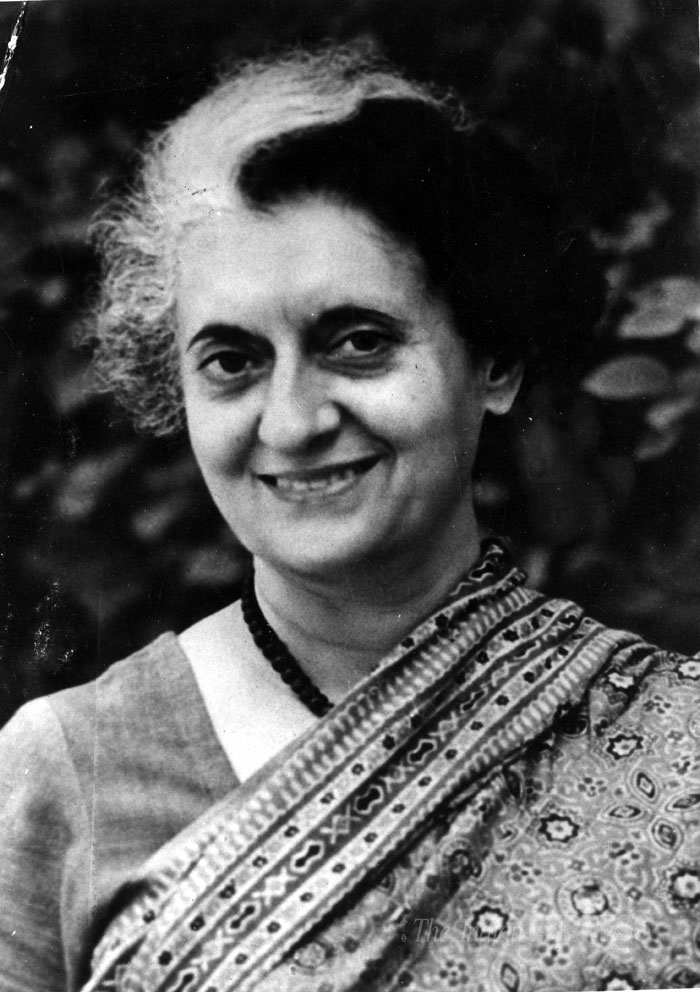

To be fair, Indira Gandhi did display some humility when she returned to power. When I met her at her residence for an interview, she was surrounded by a group of close advisers. Turning to me, she said, ‘Yes, I made a mistake.’

Sanjay was even more remote. He was now an MP in his own right and had acquired political legitimacy. The big question in everyone’s mind was what he and his wife Maneka would do. The public was frightened of them, as the speculation was that they could get away with anything, including committing atrocities.

As it turned out, there was no need to be concerned. One late afternoon Sanjay drove to the Safdarjung Flying Club from where he and an instructor took an aircraft up for a spin. The plane crashed a few minutes later and both Sanjay and his instructor were instantly killed.

Indira Gandhi went back to the site of the crash and there was speculation at the time that she was searching for the key to a safety deposit box. Pictures taken at the time showed a devastated mother and there was admiration for the composure and dignity that she displayed.

From then onwards it was downhill all the way for Indira Gandhi. The Congress started to lose its lustre, especially in the party’s stronghold of Punjab. It so happened that the country’s President at the time was a Sikh, Giani Zail Singh, Indira Gandhi’s own nominee. Later the two fell out because Indira’s new heir apparent, Rajiv, suspected that Zail Singh was quietly assisting Sikh terrorists.

In a bid to control Zail Singh and his friends among the Akali Party, the Congress came up with a solution in the shape of a Sikh preacher called Sant Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale. No one knew that Bhindranwale would in turn become a Frankenstein, using his power of oratory and deep knowledge of Sikhism to challenge the Congress.

As his popularity soared, it became clear that he wanted to be recognized as a power in his own right, something that Indira Gandhi was afraid to give him. He said that he did not want Khalistan (an independent Sikh state), but if it was handed to him he would not say no. From the safety of his headquarters inside the Golden Temple, he issued challenge after challenge to the government in New Delhi. He even went so far as to publicly abuse Indira Gandhi.

The prime minister picked up the gauntlet and ordered the army to storm the Golden Temple, the Sikh Vatican, sacred to the Sikh community. When the army encountered stiff resistance from the heart of the Golden Temple, a decision had to be made about whether it would be appropriate to use tanks. Indira Gandhi was woken up in the middle of the night to ask if the security forces could go ahead with all guns blazing. She gave her approval, but in the process alienated the entire Sikh community.

To this day even moderate Sikhs argue that other methods could have been used, such as cutting off all water and electricity supplies. Why, they ask, did their beloved Golden Temple have to suffer such desecration ?

Book cover: Of Leaders and Icons Speaking Tiger

Among the alienated Sikhs were the prime minister’s two hitherto ultra loyal Sikh bodyguards deployed at the entrance to the prime minister’s residence. Soon after the Golden Temple operation, on 31 October 1984, Indira Gandhi had a television interview scheduled with renowned film producer and actor Peter Ustinov. At 9.20 a.m. that morning, as she walked across the lawns connecting her residence, 1 Safdarjung Road, with her office, 1 Akbar Road, where the interview was to be held, the two bodyguards, Beant Singh and Satwant Singh, opened fire, pumping their bullets into Indira Gandhi. Beant Singh shot her with his pistol. As she fell to the ground, Satwant Singh fired at her with his Sten gun. Her secretary, R.K. Dhawan, who was accompanying her, told me that he was at a loss to believe what he was seeing. Beant Singh said in Punjabi, ‘We have done what we had to do. Now you can do what you have to do.’ Both guards dropped their weapons and surrendered to the police. Indira was rushed to the All India Medical Institute (AIIMS) where she breathed her last.

Only days earlier the Intelligence Bureau had warned that the two men posed a security risk and should be replaced. She disregarded their warnings, saying, ‘I have full faith in them.’

So successful were Indira Gandhi’s tactics that people across the country started to describe her as ‘the only man in the cabinet’. She survived every national crisis, including severe food, water and power shortages. Her greatest moment of glory came in the 1971 war when she managed to split the two wings of Pakistan, helping the emergence of Bangladesh. She was by now so popular that even political opponents like Atal Bihari Vajpayee took to describing her as the all-powerful Goddess Durga.

In her success also came the seeds of failure. Elections had taken place before the 1971 war, but in a startling, retrospective judgement four years later in 1975, the Allahabad High Court ruled that Indira Gandhi was personally guilty of electoral malpractice and barred her from holding any elected office for another six years.

After the Allahabad judgement, Indira had thought of stepping down. I believe that if she had done so and had gone back to the people for a verdict on her electoral offence, offering her apologies, she would have got re-elected. However, two persons dissuaded her from doing so. One was her principal adviser and son, Sanjay Gandhi, who completely ruled out her resignation. The other was Siddhartha Shankar Ray, then the West Bengal chief minister, who advised her to impose an Emergency. She reportedly told him that India was already under an Emergency following the Bangladesh war. He said what he meant was an internal Emergency which would enable her to suspend fundamental rights and allow her to rule as she wished.

Instead of appealing against the judgement, Indira Gandhi imposed a state of Emergency, including strict censorship and detaining her most feared political adversaries. On a personal note, I too, was detained because of my critical writing. For three months, I lived in Tihar Jail until the Delhi High Court ordered my release.

Meanwhile Indira became ever more dictatorial and paranoid. She gave full leeway to her younger and more favoured son, Sanjay, who became the real power behind the throne. It was he who launched Maruti cars and it was Sanjay again who decided on compulsory sterilization for any family that had more than two children.

When Indira Gandhi became prime minister for the first time in 1966, the authoritarian streak that later came to characterize her was not so obvious. She was quiet and kept to herself. Socialist MP Ram Manohar Lohia went so far as to describe her as the ‘goongi goodiya’ (dumb doll). This did not prevent Lohia and Mrs Gandhi from enjoying close personal relations. Years later when Lohia was jailed for some political misbehaviour, the prime minister sent him a crate of mangoes to assure him that she harboured no personal ill feeling towards him. In those early years the goongi goodiya was not used to public speaking. Her participation in the Lok Sabha was an embarrassment to the party because she couldn’t speak coherently. By the time she came to the forefront of Indian politics as the Congress leader, she was far from being a fluent orator in either English or Hindi.

Her progress in improving her oratorial skills in both languages helped her consolidate her position in the party, so much so that she managed to sideline party elders like S.K. Patil, Atulya Ghosh and even Kamaraj, who had made her a cabinet minister. Once after they had been well and truly relegated to the shadows, I bumped into Kamaraj and asked him how he explained Indira Gandhi’s style of government. Kamaraj looked at me and hit his forehead with the palm of his hand, to express his helplessness. Indira concentrated power in herself and brooked no criticism.

She gave that message to newspapers. The Indian Express was an exception and did not dance to her tune. In retaliation she stopped all government and public sector advertisements to the Express. But it was commendable that the paper’s owner, Ramnath Goenka, left it to us on the staff to run the paper. We did not relent in denouncing her. Years later she made us the first target when she imposed the Emergency. The board of the Indian Express was changed and the Hindustan Times owner, K.K. Birla, was appointed its chairman by Sanjay Gandhi, the then extra-constitutional authority. Birla obeyed him both in letter and spirit.

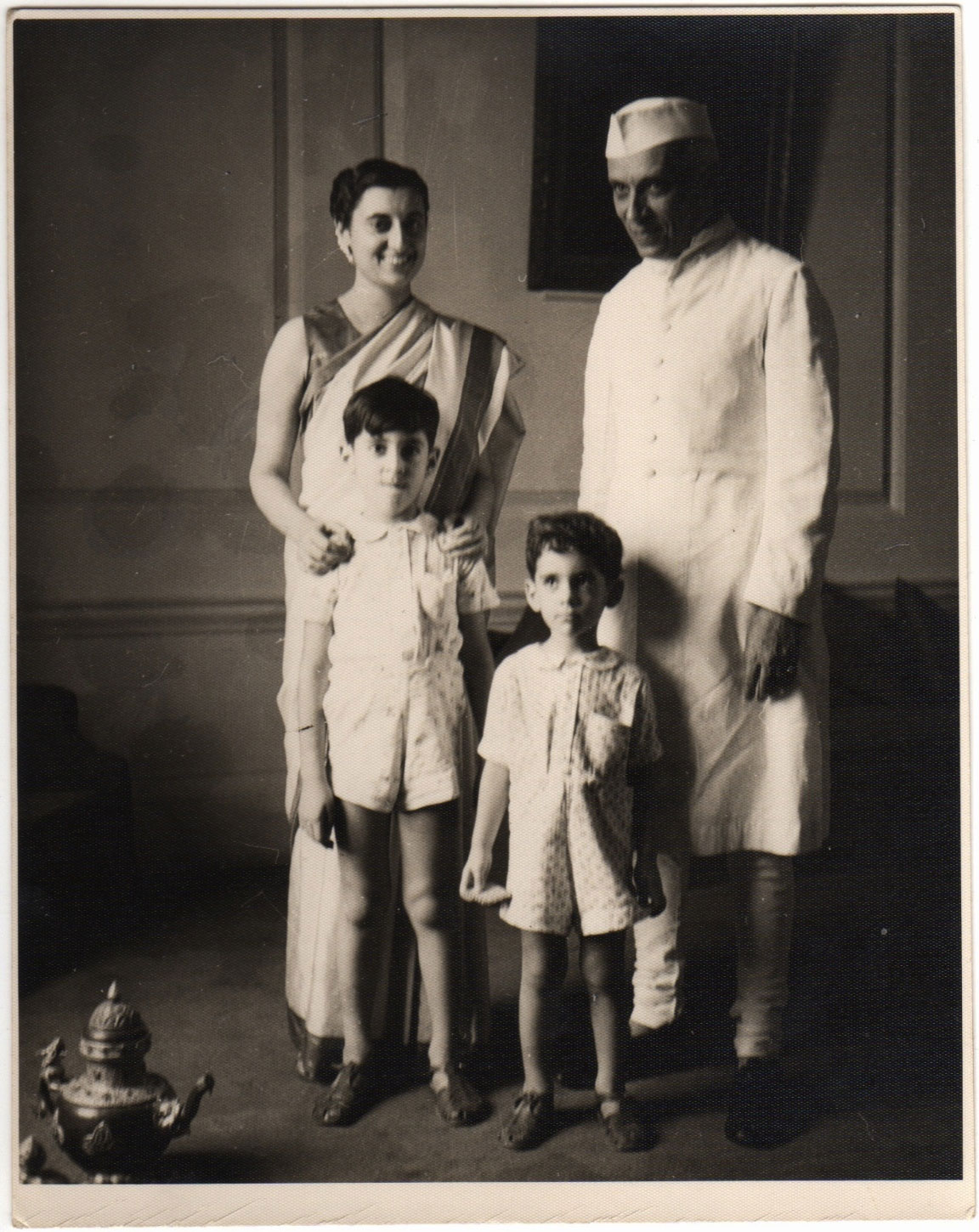

Jawaharlal Nehru with Indira Gandhi, Rajiv Gandhi and Sanjay Gandhi Wikimedia Commons

Of Leaders and Icons, from Jinnah to Modi by Kuldip Nayar. Excerpted with permission from Speaking Tiger

Jawaharlal Nehru with Indira Gandhi and her young sons -- Rajiv and Sanjay Gandhi Nehru Memorial Museum and Library

Two years after imposing the Emergency, Indira Gandhi felt the need for political legitimacy. She did not like being called a dictator and was very encouraged when the Intelligence Bureau (IB) told her she would win any election hands down. In fact, the opposite happened. The Congress lost heavily, particularly in North India, and Indira Gandhi was forced to resign.

I was given an appointment to come to the prime minister’s house. She was outside in the garden. When she saw me she walked towards me. But I looked at her and said, ‘Today I have come to see Sanjay.’

Her political heir apparent was standing some distance away, under a tree in the garden. I got an inkling of Sanjay Gandhi’s thinking during our conversation. I was writing my book, The Judgement. Kamal Nath, his friend and a director on the Indian Express Board, had arranged the meeting. My first question to him was: How did he think he would get away with it? He said that if elections had not been held they would have been running the government. Then, why did you hold them? I asked. ‘You should address that question to my mother,’ he said. ‘In my scheme of things, there were to be no elections for three to four decades.’

Sanjay Gandhi (right) was Indira Gandhi's favoured son. About her older son, Rajiv, she used to say, ‘He doesn’t know anything about politics.’ Nehru Memorial Museum and Library