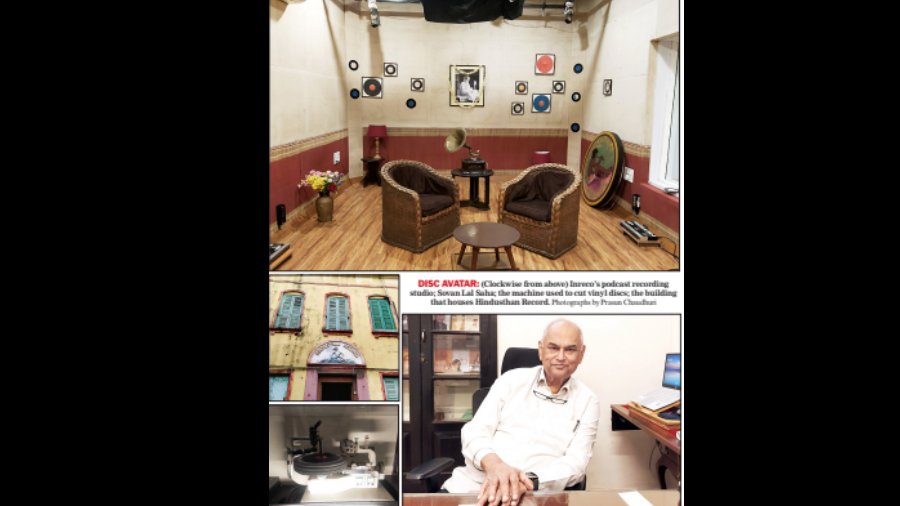

Act I: The two-storey house on 6/1 Akrur Dutta Lane is early 20th century. The logo, carved in low relief under the arch spanning its ancient door, depicts a shepherd boy playing the flute

Both house and logo belong to Hindusthan Record, the first record company to be owned by an Indian. It was in this house of Hindusthan Musical Products Ltd — as it was officially called — that the first recordings of classical music stalwarts such as Ustad Faiyaz Khan and Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan happened. Stars such as Kundan Lal Saigal, Sachin Dev Burman and Debabrata Biswas were launched here. Rabindranath Tagore’s first recorded song, Tobu mone rekho, was a Hindusthan Record offering as was poet-composer Atul Prasad Sen’s Ami jani tomare Rangalal.

The founder of the company Chandi Charan Saha — better known as C.C. Saha — went to Berlin in 1932 to buy the first recording machine from Georg Neumann, a leading manufacturer of audio equipment. Saha family legend goes that Saha was introduced to Tagore in Heidelberg that same trip.

That year, two other Bengali entrepreneurs — J.N. Ghosh and N.B. Sen — founded the labels Megaphone and Senola to record Indian music. All three companies had big stores in the Esplanade area and sold thousands of discs. Megaphone exists, but Senola is now defunct.

Saha’s younger son Sovan Lal says, “Tagore extended his support to my father. He encouraged some of the best women singers (of Visva-Bharati) — Amiya Tagore, Amita Sen, Rajeswari Dutta and Kanika Bandyopadhyay — to record songs with our company.” According to him, these women helped shatter the taboo on women singers from bhadralok families recording songs.

The company forayed into film music — Kanan Devi, Pankaj Mullick, S.D. Burman, Prithviraj Kapoor. From the 1940s, Hindusthan Record extended its repertoire to Punjabi, Bhojpuri, Odia, Chhattisgarhi and Nepali music, qawwalis, bhajans and aartis.

But their niche market was Bengal and they kept churning out bestseller discs of artistes like Debabrata Biswas, Subinoy Roy and Purna Das Baul. New Theatres Studio, a film production company at Tollygunge, tied up with Hindusthan Record and marketed playbacks by Kanan Devi, K.C. Dey and K.L. Saigal. The senior Saha’s friendship with B.N. Sircar, film producer and founder of New Theatres, helped sell discs of musical talkies Mukti, Bidyapati, Debdas, Parichay.

Sovan Lal tells the story of how his father helped launch the musical career of S.D. Burman. He says, “Sachinkarta used to give music lessons in this house. He met his wife Meera Dasgupta here; she was his student.” He also talks about how Saigal refused offers from other record companies and remained with Hindusthan Record. Apart from playbacks for films, Saigal recorded ghazals (Urdu and Persian), Rabindrasangeet and modern Bengali songs for them.

The company’s heyday continued until 1948. And then there was a tremendous shortage of shellac, a natural resin, used to make the discs. During World War II, shellac was used in large quantities to make artillery. The company that mass-produced their records — the Gramophone Company of India — refused to manufacture discs for Hindusthan Record. They preferred to promote their own labels, such as HMV. Says Sovan Lal, “My father had failed to read the crisis and the competition. He had not built a disc factory even though he had bought land for one.” As a result, Hindusthan Record lost the edge to competing brands and senior Saha lost interest in the business.

Act II: In 1976, after Saha’s death, Sovan Lal and his elder brother Mohan Lal decided to rejuvenate the business. They launched the Indian Record Manufacturing Company, or Inreco, and started a record manufacturing unit in Taratala on the southern fringes of Calcutta.

By then vinyl discs had replaced shellac records.

Inreco started with a wide range of artistes across languages — Tamil to Malayalam, Punjabi to Bhojpuri, Marathi to Odia. Lata Mangeshkar, Asha Bhonsle, Pandit Mallikarjun Mansur, Kumar Gandharva, Ustad Amir Khan and Manna Dey were among the artistes it recorded. They were able to ink deals with Bengali film directors in Bombay — Hrishikesh Mukherjee and Sakti Samanta gave them rights to some super-hit Hindi movies. They also struck deals with Tamil composers such as Ilaiyaraaja and classical Carnatic singers such as M. Balamuralikrishna.

But in the Left Front era, labour troubles erupted. Says Sovan Lal, “The cache of our priceless recordings lay in the locked-down factory for months. After much struggle and lengthy negotiation, we were able to rescue the master discs.” And then Inreco went bankrupt.

The wheel of fortune did not turn until the late 90s. With the advent of mobile phones, there came a demand for a new kind of music — ringtone music. Now, ringtone music is protected by copyright and mobile service providers ensure payment to recording companies. The musical compositions of both Hindusthan Record and Inreco made brisk business and this helped them repay all debts

Sovan Lal digitised much of their repertoire for the new media and soon enough the vast corpus was made available on OTT platforms such as Amazon, Spotify, iTunes and YouTube.

“My dream is to digitise all traditional records of ours as well as various companies and upload them on a cloud platform that can be accessed by all music lovers free of cost. The legacy must be preserved,” says Sovan Lal. He is currently busy negotiating with representatives/ inheritors of Megaphone, Senola and even All India Radio (AIR).

He tells The Telegraph, “We retrieved the historic recording of the radio drama Shah Jahan written by D.L. Ray and produced by Birendra Krishna Bhadra from AIR, Calcutta, recently.” He is also approaching private collectors.

Devajit Bandyopadhyay, a musician, collector and archivist, says, “I am eager to get my collection of fragile shellac records of theatre and classical music digitised for this unique project.” He stresses on the fact that, unlike recorded music which could only be enjoyed by elites, digitised music can now reach the masses.

Digitisation of the recorded classics is now happening at a frenetic pace in multiple studios on the premises of Hindusthan Record at Akrur Dutta Lane. So don’t wonder should you be in those parts and K.L. Saigal’s Balam aaye baso morey man mein floats into your ears or Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan’s Tore naina jadoo bhare.