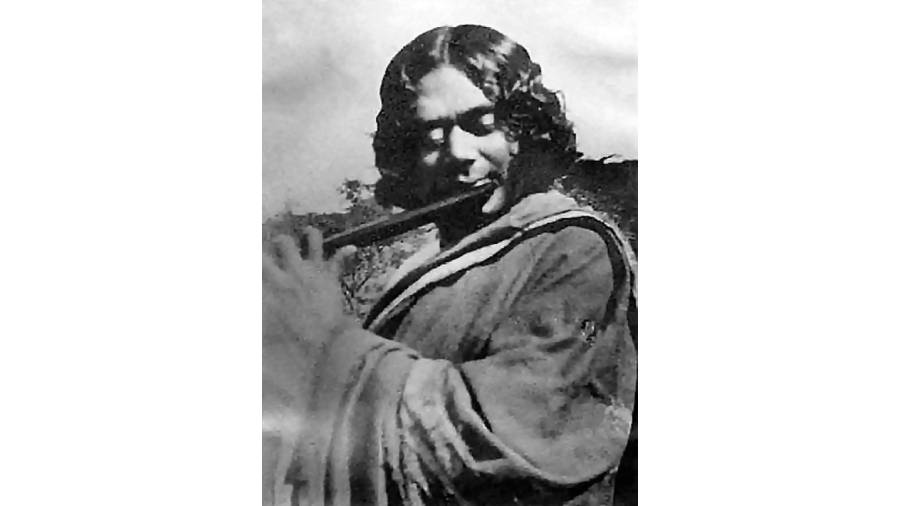

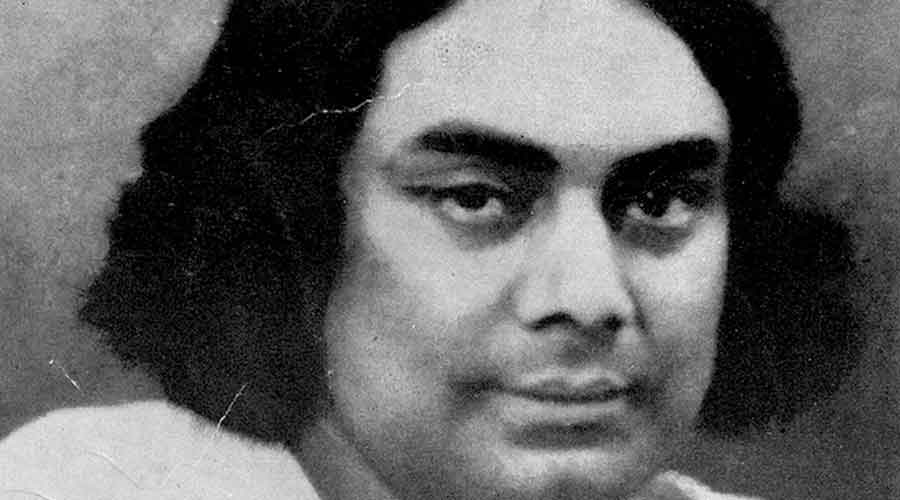

To say that May 25 or Jaistha 11 and August 29 or Bhadra 12 don’t ring a bell in these parts any more is no exaggeration. And yet they are the birth and death anniversaries of a genius poet, writer and musician. The same who earned the sobriquet of bidrohi kobi, or rebel poet, for his eponymous poem written against the backdrop of the non-cooperation movement exactly a hundred years ago. The man who composed over 3,000 songs, which led to the creation of a genre now known as Nazrulgeeti. The poet whose creations ushered an Indo-Islamic renaissance of sorts. The activist who wielded his pen against colonialism, religious fundamentalism, elitism and fascism. The boy from an obscure village in south Bengal, who went on to become playwright, novelist, journalist and freedom fighter. Kazi Nazrul Islam.

Till the late 1990s, recordings of Nazrul’s poem Bidrohi — in the voice of his eldest son Kazi Sabyasachi — would be played at puja pandals, political rallies and cultural programmes. I remember his voice sombre, the pronunciation clear, the lyrics throbbing with power and emotion: Bolo bir,/Bolo unnoto momo shir... Say, Valiant,/Say: High is my head! An exhortation to rebel against all forms of oppression and especially against the British colonialists.

***

The Nazrul Centre for Social and Cultural Studies or NCSCS is in Asansol, near Churulia village where Nazrul was born. Says Swati Guha, who is the director of NCSCS, “Nazrul is known for his poems and songs, but very few know about his novels, short stories, essays and editorial pieces from the journals he edited.”

Nazrul was the editor of Bengali journals such as Dhumketu (Comet) and Langol (Plough). In fact, his foray into the Bengali literary scene was with the short story Baunduler Atma-kahini (Autobiography of a Vagabond) published in one such journal called Saogat (The Gift). Nazrul had written the story in Karachi in 1919; at the time he was a havildar with the Bengal Regiment there.

Guha continues, “Even his headlines were hard-hitting. It’s time we learnt to appreciate the vast corpus of creativity of this little understood maverick genius.” By way of celebrating the 100th anniversary of Bidrohi, NCSCS has decided to have the poem translated into 100 Indian languages and dialects.

For all its richness, Nazrul’s creative life was quite short-lived, a little over 20 years. At 42, he was struck by an ailment of the brain called Pick’s Disease; it caused permanent mental and physical damage.

“I believe he was a child prodigy,” says musician and archivist Devajit Bandyopadhyay. “Exposure to folk theatre early in life helped him pick up skills as a poet, playwright and music composer,” says Bandyopadhyay who is writing a book the working title of which is Nazruler Natyasangeet.

Born in 1899 into a poor Muslim family, Nazrul received religious education at the primary level and worked as a muezzin in a mosque till he was 10. He studied in a formal school up to Class X. And till he joined the British Army, he had worked as a domestic help, a helper in a bakery and in a leto troupe, a travelling folk musical.

Nazrul began learning Bengali and Sanskrit literature, in addition to his childhood education in Persian and Arabic, to polish his skills at leto gaan. Says Bandopadhyay, “We have been discovering hundreds of unpublished songs and music compositions by him... He would mix Indian classical music with Middle Eastern tunes.”

Nazrul married Pramila Devi, a Hindu, and named his first two sons Krishna Mohammad and Arindam Khaled. Both the boys died in infancy. The two younger boys were Kazi Sabyasachi and Kazi Aniruddha.

Nazrul used Perso-Arabic and Sanskrit in all his works. In his poetry and devotional songs, he brought together with ease gods from the Hindu pantheon and Prophet Muhammad. Quite expectedly, he was criticised by the custodians of Hinduism as well as orthodox Muslims for this. He was physically attacked more than once. In response, he wrote an essay, Mandir O Masjid, which was published in the Leftist journal Gana Bani. Here’s a translated line: “Hearing the weeping of the wounded, the mosque does not waver, nor does the Goddess-in-stone of the temple respond.”

But all this came later. Says Sumita Chakrabarti, former Nazrul Chair Professor at the University of Burdwan, “Nazrul’s popularity was at its peak between 1920 and 1940 as his poetry and songs inspired both freedom fighters and ordinary people desperate to get rid of the colonial masters.”

But how did he get there?

Of course, you could argue that some people are born wired in a certain way, but there is no ignoring influences and life experiences. Inspired by the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, Nazrul unleashed his attack on inequality and injustice in society through poems such as Sarbohara (The Proletariat), Samyobadi (The Communist), Daridro (Poverty) and Anandamoyir Agomone (Welcoming Anandamoyi).

Soon after the publication of the last poem in 1922 — in which he compared British India to a “butchery” wherein “God’s children” were whipped and hanged by the British — the authorities arrested him on the charge of sedition and sentenced him to a year of rigorous imprisonment. In court, Nazrul shocked all by representing himself and reading from his essay Rajbondir Jobanbondi (The Deposition of a Political Prisoner). It contained an explosive couplet, which reads thus in translation: The tyrant’s oppression of truth/Must diminish/That truth, my God/ Shall establish.

Nazrul’s liberal and socialist views were strongly influenced by Muzaffar Ahmad, one of the founders of the Communist movement in India. Nazrul and Ahmad together founded the Labour Swaraj Party, one of the earliest Left outfits in India, they wrote the party’s pamphlet and edited the mouthpiece Langol.

It would not be incorrect to say that his imprisonment and deposition catapulted Nazrul into a different orbit — of fame, of achievement. And yet, there has always existed a section of people who try to dilute any discussion of his genius by labelling him a populist.

To this day, a large section of Bengali intelligentsia considers his literature low-brow, targeted at semi-literates and bereft of aesthetics. In these circles, Nazrul is usually referred to as the “havildar kobi”. “Intellectuals in post-Independence India considered his literature too loud and arrogant,” adds Chakrabarti.

***

When Bangladesh was born in 1971, Nazrul was still alive but ravaged by his illness. The new nation, however, chose him as its national poet.

Reminds Chakrabarti, “In West Bengal too, after the Left Front came to power, Nazrul’s poems were included in the school syllabus. Academies were founded, which were supposed to encourage research on Nazrul; auditoriums and roads named after him.” When the Trinamul came to power, it founded the Kazi Nazrul University in Asansol; the Nazrul Tirtha, a cultural centre in New Town, Calcutta; and the research academy NCSCS.

But if you were to ask me, despite all these efforts, Nazrul has all but disappeared from the minds of Bengal’s men and women.

As for me, I miss the baritone voice of Kazi Sabyasachi reciting lines, the razor edge of which remains undiminished by the years. The lines from Nazrul’s Kandari Hunsiyar or Beware, My Captain run thus, “The boat is trembling,/The water is swelling,/The sail is torn asunder... ‘Are they Hindus or Muslims?’ /Who asks this question, I say. /Tell him, my Captain,/The children of the motherland are drowning today.”