When Anita Bose first arrived in Thailand she was surprised to see how integral to its culture the Ramayana was. Buddhism is followed by 95 per cent of the population and yet it was, and still is, compulsory to study the national epic, Ramakien (meaning Glory of Rama), in all government schools. Then there is the popular dance form of khon that portrays episodes from Ramakien.

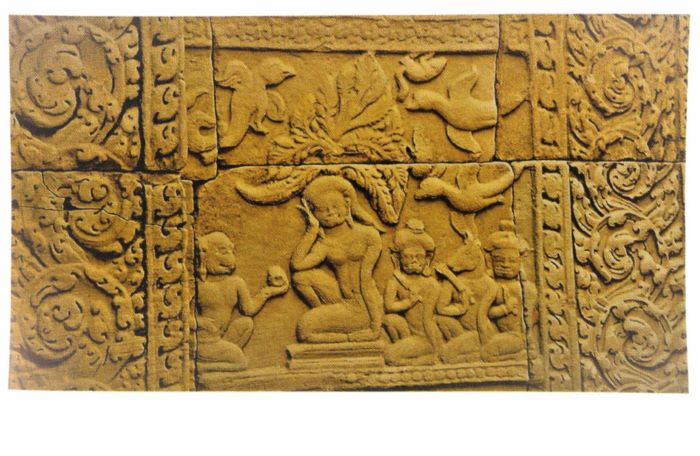

Courtesy, Anita Bose

It doesn’t end there. A month-long Ramayana festival is an annual royal event, in which eight nations, including India, participate. And even the king of Thailand assumes the title of Rama at his coronation.

In subsequent years, Bose had the opportunity to travel the rest of Southeast Asia. The writer of the book, Ramayana: Footprints in South-East Asian Culture and Heritage, tells The Telegraph, “Increasingly I realised that the Ramayana does not stand for religion in these countries. It has been embraced in Muslim, Buddhist and Christian majority nations as well.”

A Thai dance representation of the Ramayana Bhubaneswarananda Halder

Indeed, Ramayana ballets are held on full-moon nights at the Prambanan Temple complex in Indonesia. Cambodian peasants turn to the Rama Kerti when they are concerned about the fate of their crop. And Malaysia has its own Hikayat Seri Rama, a Malay adaptation of the epic.

Bose volunteered as a guide at the National Museum in Bangkok for five years. She says, “They have a Ramayana room. Nowhere else have I seen so many Ramayanas in one place. In the Mother of Pearl gallery, there is a miniature display of the story of Ramayana in a single frame in pearls. A howdah (seat fitted onto the back of an elephant) used by the royal family has Ramayana inscribed on it.”

“The Ramayana is an integral part of Thai tourism. So many artistes are engaged in khon performances,” Bose points out. Performance is a key element in Indonesia’s link with Ramayana too. At Prambanan, the largest collection of temples after Angkor Vat, the boundary walls of the pathway used to circumnavigate the temple are full of Ramayana engravings and performances take place on alternate days.

Of the many versions of the Ramayana popular in Southeast Asia, two that are famous in Java are Seratram and Kakawin. Experts talk about 1,200 editions of Seratram from east Yawadwip, pointing to its long legacy. The exact period of the composition of the Kakawin is not known, but it is usually traced to the reign of King Sindok in 929 AD. This version of the story ends with the reunion of Rama and Sita after her chastity test by fire.

Bose talks about Purawisata, a Ramayana ballet performed in the Indonesian city of Yogyakarta every evening since 1976. It starts with the abduction of Rama’s wife Shinta by Rahwana, highlights the valour of Hanoman and ends with the killing of Rahwana and the reunion of Rama and Shinta. A Muslim man has been in charge of the Yogyakarta ballet since it started. Earlier his wife used to play Shinta, now his grandchildren play as part of the vanar sena. Almost the entire cast is Muslim. “‘The Ramayana is their cultural identity, their manager told me,” says Bose. Rabindranath Tagore had seen a Ramayana performance during his trip to Java in 1927 with the linguist Suniti Chatterjee. Chatterjee has even written about the experience.

In Phra Lac Phra Lam, which is the national epic of Laos, Lac stands for Lakshmana and Lam for Rama. It is different from the Valmiki Ramayana in many ways. In one version, Sita is Ravana’s daughter while Rama and Lakshmana have a sister named Chanda, whom Ravana abducts and marries. And Hanuman is Rama’s son. But there are similarities too. In her book, Bose writes that stories of the Ramayana are believed to have been recited by the Buddha and are popular as Phra Ram Xadok or the Jataka Tales.

In Kamboj, today known as Cambodia, the Ramayana is known as Reamker or Rama Kerti. The Kamboj poet has described Rama not as god but as a human being of superior nature. The narrative begins with Rama’s exile in the forest, triggered by Kaikeyi’s jealousy, and ends with Rama bringing Sita back to Ayodhya from Valmiki’s ashram along with Lav and Kush. Sita’s disappearance into the Earth when asked to prove her chastity finds no mention in this version.

The Ramayana is embedded in Cambodia’s social customs. According to Bose, peasants do a recital of the epic if they fear drought. The part they choose is where Kumbhakarna physically chokes the water supply to the vanar sena, but Hanuman and Angad remove his gigantic body using magical powers, thus restoring supply.

In times of natural calamity, farmers of this Buddhist-majority country go to the monks to seek relief. The monks open Rama Kerti and place a stick on a random page. If it opens at a positive episode like Hanuman fetching medicinal herbs or Rama and Sita returning to Ayodhya, it is considered a good omen, but if it opens at something like the abduction of Sita then it portends ill.

That would probably resonate with communities here at home who play much the same games with volumes of the Ramcharitmanas.