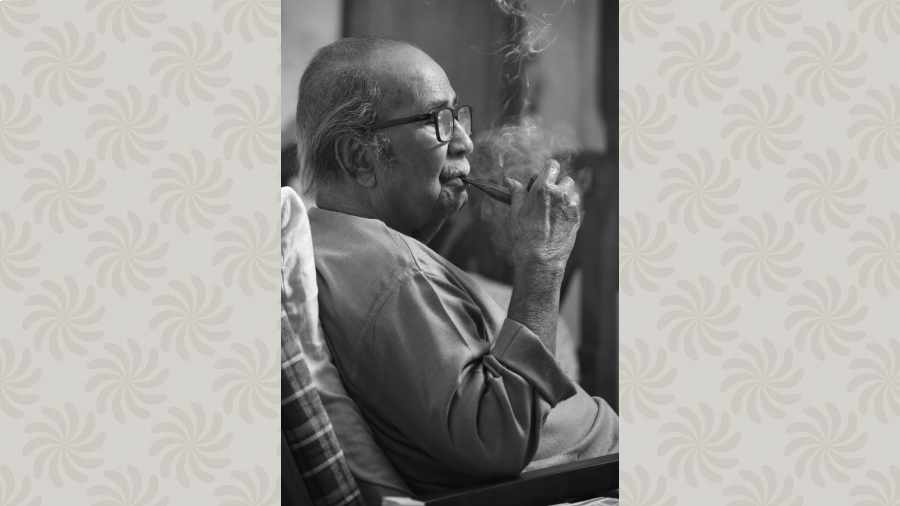

The close-knit grandson and grandfather have practically gotten soldered through the pandemic. Stories that never came to the lips now stream 24x7 into greedy young ears. It is from his grandfather that the boy absorbs all kinds of information. The taste of gur from his boyhood, the famine of 1943, how to dice potatoes perfectly, the difference between handwritten text and the printed word. Amitendu is barely 17, roughly the same age as Dibyendu Chaki when he left Naogaon (in present day Bangladesh) for Calcutta in 1948.

Amitendu is perhaps the first to want to know about Chaki’s life’s experience in all its excruciating detail. It is he who infuses with excitement and pride a tale the 92-year-old himself tells clinically. It is almost as if having found this young custodian of his story, the elder has freed himself of the weight of his own history.

An art college graduate from the 1950s, Chaki could never be a full-time artist despite having the talent. The Partition had uprooted his otherwise well-off and large family — he was one of nine siblings — in installments. Thereafter, to use his own words, life became one long “crisis”.

Chaki talks about his staccato life post the shift. Looking for a place to stay. Mechhua Bazar. Paikpara. Uttarpara. Ariadaha. Bringing over his siblings. Looking for a job. Helping his siblings with their education. Starting his own family. “I didn’t leave art, but I couldn’t really give it my full concentration,” he tells The Telegraph. As if to make up for it, he spent what little time he was master of in the pursuit of art.

He made murals, Durga, Kali and Jagaddhatri idols and, as an expert calligraphist, created the title credits of the Bengali film Baimanik. One of the earliest how-to-draw books for children in Bengali, Chhobi Aankar Mawja, was by him. He worked as an illustrator for the advertising agency J. Walter Thompson and the Saraswati Book Depot, and freelanced for Anandabazar Patrika. Amitendu has heard that his grandfather would start his day at 3am for the greater part of his working life.

Amitendu says, “Grandfather is an artist, but he doesn’t seem to see himself as one. It is all about livelihood and doing what had to be done to support a family…”

Talking about seeing, Chaki has spent a good part of his working life inside others’ eyes, quite literally. He retired as an artist-cum-micro photographer with the eye department of Calcutta Medical College — a job most likely done by HD recording systems now.

He talks about microscopes fitted with German cameras — he cannot recall the name — and how he was required to take photos of the slides. Chaki says, “I went to Tapanbabu, who was in the pathology laboratory. He told me I had to focus on the diseased area.”

And what art did he bring to the job? It seems while the ophthalmoscope reveals to the doctor the inside of the patient’s eye, those days fundus photography could not capture all that needed to be recorded for purposes of research and further study. So, in certain cases, the doctors required Chaki to look through the ophthalmoscope and capture in drawings what he saw.

Chaki tells his story gently, with a laugh, some detail, many gaps and a litany of olden names. If someone can take in all of these and also read between the times one would have lived a stretch of history. For you see, Chaki has been retired these 34 years, which is longer than the period he worked for, and his working and non-working life together span at least two generations.

The medical college posting was not Chaki’s first job though. He was actually on lien from the Cultural Research Institute of the West Bengal government’s tribal welfare department. He had joined the place in 1957 at a salary of Rs 100. “Grandfather did two books of photographs, The Oraons of the Sunderbans and The Tribes of West Bengal, while at the institute,” says Amitendu. Chaki’s response: “They were the institute’s publications. They carried my photographs as I was their designated photographer.” Amitendu does not relent. “You made a colour documentary on the Birhor tribe during this time.” Chaki’s interjection: “A very short one; barely 15 minutes.” Amitendu wants it to be known that it was during this time that Chaki did the children’s drawing book. His grandfather’s addition, “But it was published under your grandmother’s name — Sunanda Devi — as I was a government employee.”

Amitendu does not give up. His grandfather has told him how during his first year in art college he met the famed artist and puppeteer Raghunath Goswami and did puppet shows with him. “You did a show at the novelist Tarashankar Bandopadhyay’s house, didn’t you,” he asks. Chaki confirms, but confesses he cannot remember details.

Amitendu knows his grandfather went to see Abanindranath Tagore and Jamini Ray with his friends to request them to contribute to their handwritten magazine Madhukori. “Tell that story,” he urges. Chaki says sedately, “Abanindranath met us but he was very frail. He didn’t quite have the strength to comply with our request.” Jamini Ray did a watercolour. “And there is that photograph of yours with Indira Gandhi,” Amitendu prompts. “That was in my fifth year. The Tata tableau was to be on display at the Republic Day parade and being part of it was my field assignment. We met Dr Rajendra Prasad. We met Nehru…” Chaki recounts.

The grand medley continues...