Reams have been written on Francis Newton Souza, the Indian artist who won fame and fortune in Britain initially and later in New York. This month, a still life by him commanded a price of $2.16 million at a Christie’s auction in New York. But few know the inside story of how he embarked on his autobiography in the mid-1970s.

Souza died on March 28, 2002, following a heart attack, leaving behind a trail of mistresses and former wives. He was buried in Mumbai. M. F. Husain, the painter, paid tribute to him. “He was my mentor. He is the most significant painter, almost a genius,” Husain was quoted by christies.com as saying. Twenty years later, Souza continues to figure in the pantheon of modern Indian artists.

He would not have been surprised at Husain’s tribute. “I discovered Husain. He was painting billboards in Mumbai,” Souza told me.

I met Souza at the Indian Consulate in New York at a farewell party for my father in the early 1970s. I was a rookie 20-something journalist on leave from a leading Indian newspaper. Hungry for bylines, I asked him for an appointment. I wanted to write about him, I said. Souza agreed to meet me, before presenting my father with a watercolour, which was eventually handed down to me.

That meeting at the consulate set the stage for a friendship with one of the founders of the Progressive Artists Group and a man described as the enfant terrible of modern Indian art. It would over time trigger many wide-ranging conversations at his apartment on New York’s West Side.

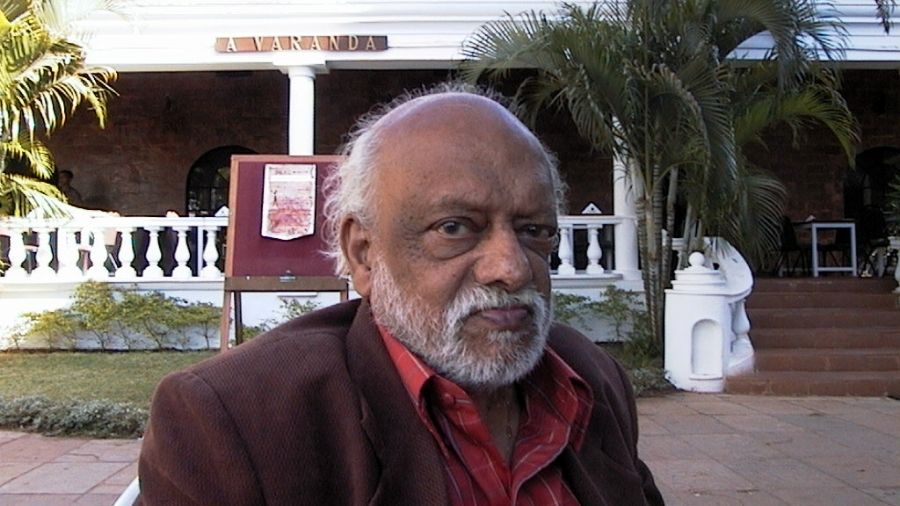

Souza was then a fading star on India’s art firmament, I mistakenly believed. He wasn’t striking looking. Then in his early 50s, he was diminutive, had a scraggly beard and was dressed modestly — as I would describe him in print; he strongly demurred.

We had freewheeling discussions and he also told me of his heyday in Britain, where he had built a reputation early and made good money. He had moved to London in 1949, met Stephen Spender the poet and written an essay in Spender’s Encounter magazine. That essay, Nirvana of a Maggot, in turn attracted the attention of a major art dealer who invited him to exhibit at his gallery. Souza’s works sold out at the 1955 exhibition. He would go on to be one of the five UK artists to be short listed for the 1958 Guggenheim international prize. So Francis Souza had made it to the big time in his early thirties.

But such heady success extracted its own price. He could often be found on the beaches of Goa drunk for days, he said. But better sense finally prevailed and he became a teetotaller.

I did write an article on him. It appeared in a Delhi-based newspaper. He evidently liked it because he telephoned me one day and asked me to drop by. When we met that evening at his apartment, he offered me a proposition. He liked my writing style, he said, and wanted me to edit his autobiography. He would write a chapter and give it to me to edit.

A sketch of the author by Souza

I agreed to edit the book but laid down a few conditions. I didn’t want to be paid but stipulated that I should be credited on the book’s cover with the editing. Souza agreed and signed an agreement to this effect which I had drawn up.

Over the next few weeks I would show up at his flat and collect a chapter he had written, edit it at home and type it, before returning to Souza’s abode. I would years later show the manuscript to an art critic in Calcutta, who exclaimed: “Souza writes very well.”

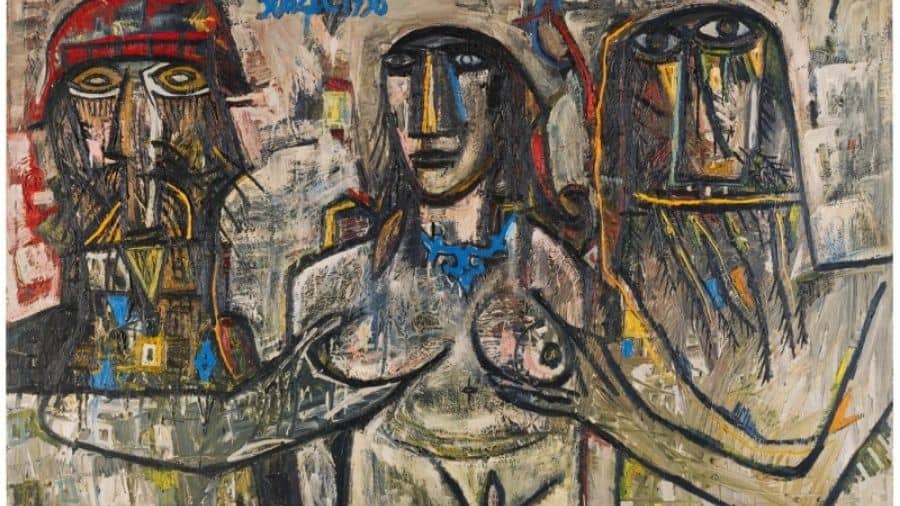

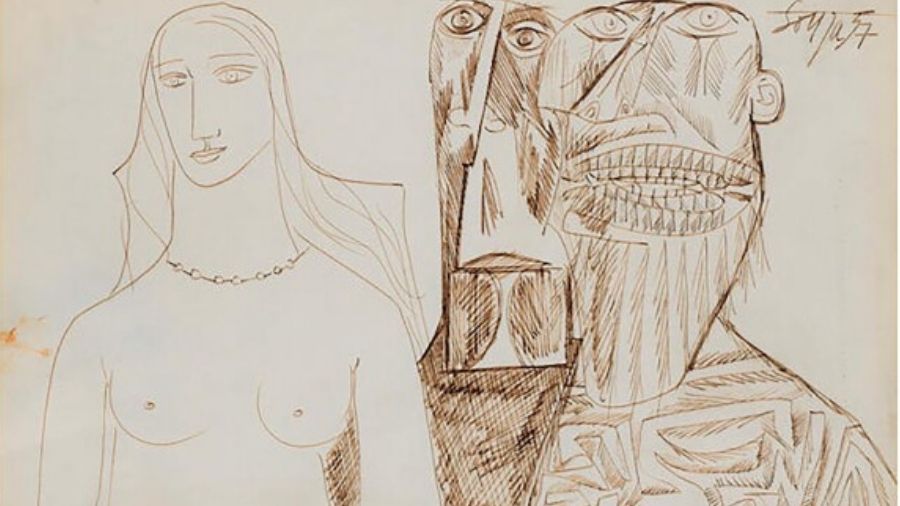

His New York apartment was cluttered with his paintings. There were paintings in the drawing room, the corridors, scattered everywhere. Of ejaculating phalluses juxtaposed against symbols of the Roman Catholic Church. Souza, remember, was a rebel, a controversial artist who was thrown out of Mumbai’s St Xavier’s College for drawing pornographic images on the lavatory walls and expelled from the J J School of Arts for joining the Quit India movement. Religion was humbug and sex was supreme in his worldview.

For all this, he was a quiet man with a wry sense of humour. At a dinner party we attended at Newsweek correspondent Patricia Sethi’s house, Muchkund Dubey, then at the UNDP but later India’s foreign secretary, asked Souza: “Are you Goanese”. Souza shot back: “Go and ease yourself.” Goans are known as Goans. Souza did not enjoy the company of the influential and said as much when we walked to the subway that night.

He did like women, unquestionably. He left his Goan wife Maria for other women, eloping eventually with his second wife, the 16-year-old Barbara. They moved to New York in 1967.

What struck me at those tête-à-têtes at Souza’s apartment was the disappearance of Barbara and baby son. They had been around when I met him initially but not later. He would confirm that his wife had left him.

Srimati Lal would appear in Souza’s life much later.

I often visited Souza, not just to pick up bits of his autobiography but to chat with him. He was an interesting man, and wanted company and our conversations ranged over many topics. One day he tried to show me the basics of drawing a face after making a quick sketch of me. It lay in my cupboard for years, till the day I learned that Souza sketches sold for Rs 20,000 upwards.

Like many self-educated people, the artist had read widely on some subjects but not on others. One evening he startled me. “You wear brightly coloured shirts to attract women. That’s what birds do. They have bright plumage to attract the opposite sex. “

I told Souza that I had ambitions of becoming an art critic. He said he would give me a letter of introduction to artists in India. “Some of them are quite snooty” he told me. And when I said that I was returning to India, he insisted on my visiting his former wife Maria in London who ran an art gallery there. I did drop in on her in London. She evidently still adored him.

I never saw Souza again. He had suggested that I continue editing his book from India. I never did. Why did I betray a man who had become a friend and who was also a premier artist? I was young, callow and foolish. And intent on building a career. Mea culpa.

It’s a cross I will bear till the end of my days.