When Pulin Behari Makhal turned 100 last December, some old boys of Calcutta’s St. Lawrence School decided to seek him out. Pulin Sir, as he is commonly known, had been their games teacher all through junior and senior school. Says Ashim Campoo from the class of 1981, “It was not difficult to find him. We knew Sir must have retired and gone back to his hometown in Morapai in Magrahat, a small town in South 24-Parganas. The Morapai parish was sure to have his details.”

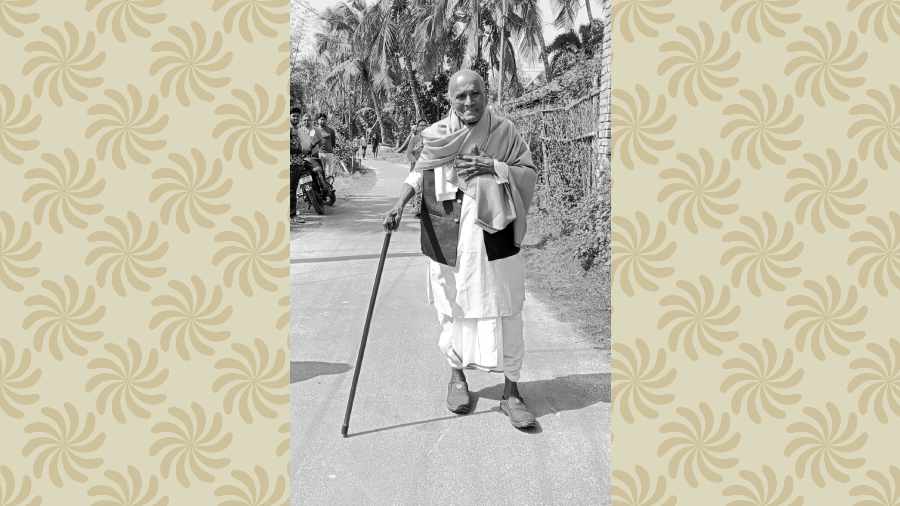

As it turned out, in Morapai, even little boys and girls can point out Pulin Sir’s house. That day, Campoo and his friends caught “Sir” on his way back home from his morning stroll. He had his walking stick in hand but he stood upright. “My father is almost deaf but he does not need glasses,” says Ratan, his youngest son.

Pulin Sir had joined St. Lawrence before Independence, no sooner than he was out of college. He used to stay in an accommodation provided by the school between 1943 and 1967, when he was the hostel warden. Those days, the school was in south Calcutta’s Park Circus area. Pulin Sir recalls, “But then when the Japanese started bombing, the first bomb fell on Kidderpore, and I returned home. After two years when the school reopened, it was shifted to Ballygunge Circular Road.”

Pulin Sir enjoyed gymnastics since he was a schoolboy. Jayanta, his eldest son, says, “My father had studied in the Balrampur Primary School in Morapai block and later went to a boarding school in Bishnupur in South 24-Parganas. It was there that he started showing exceptional skills in gymnastics and sports. He would rank first in swimming.” Later, he went to a school in Dum Dum in north Calcutta. “And this is where he received more formal training in gymnastics,” he adds.

Interrupting the long flashback, Isaac Gomes recounts how during games periods, Pulin Sir would never shout, he would only wield his long-necked whistle. “The sound of it would compel us to be orderly,” he says. This would be the early 70s. “I did not believe in scolding,” says Pulin Sir. His ancient voice quivers as he speaks. He continues, “Children were excited about playing outdoor games and activities. For boarders, there was an unwritten rule that from three in the afternoon to five, they had to be out in the playground,” remembers Ratan, who is also an ex-student of St. Lawrence. “If you were indoors and got caught, other students would throw colours on you,” he says laughing at the memory.

Campoo remembers Pulin Sir coming to school every day in a white dhoti and kurta. “That is what he wore throughout his life. Only on Sports Day, he would wear white trousers and a white T-shirt,” he says.

Pulin Sir is still remembered for his annual Sports Day shows. His students recall the human pyramids he taught them to form by climbing on to each other’s shoulders. He also taught them to go through the fire ring.

Turns out he had seen these acts in a circus. Father Pinto, who was the principal of St. Lawrence in the 1960s — Pulin Sir cannot recall his full name — encouraged him to adapt these. He even bought him a book wherein many such acts were described in detail.

What about the parents of students? Didn’t they object to such goings-on? Pulin Sir seems surprised at the suggestion. He replies, “No, no, why would parents object? They would be proud and happy to see their wards’ splendid performance.” Gomes adds, “Life was better in fact; our school used to conduct parent-teacher football matches. Sports were a part of life.”

Almost everyone remembers Pulin Sir as a man with a great physique. His son Jayanta recalls how there was a time when Pulin Sir had to travel every day from Morapai to Ballygunge. Bonolata Naek remembers how her father would get up at three in the morning, walk for eight kilometres to the Magrahat station, take a train to Ballygunge and then walk for another three kilometres to school.

“On off days, he would climb the date palm to collect sap. Every week he would clean the ponds on our property. His fitness came from his daily rigour,” she says.

On one side of Pulin Sir’s home in Morapai are green paddy fields that seem to stretch up to the horizon. “My grandfather, who was a potter, had bought most of the land,” says Jayanta. From the time he retired in 1988 to now, Pulin Sir makes it a point to work in the fields to keep himself fit.

Pulin Sir’s daily chores have not changed, nor has his passion for fitness. He cannot understand the youth today though and their love for the indoors. Pulin Sir says, “I don’t know what has happened to this generation. They are stuck to their phone. But my village is not like that.”