Some people have an element of poetry about them. She is like that.

There are plenty of flower sellers in this south Calcutta neighbourhood. Dishevelled women at street corners with scant and scattered wares who sit from morning to late afternoon. Older men in short dhotis walking up and down the road every other evening with baskets of unsold bel. The shop boys who hover around the semicircle of flower stalls outside the big bazaar sell fancy flower arrangements. They will sprinkle tinsel on a bouquet of Bangalore roses, wrap orchids in dreamy pink paper. Inside the smaller market, there is a no-nonsense shop that stocks puja flowers. The generational shop in-charge does feverish business, constantly leaps off and onto the raised perch. Short story, drama, novella, aphorism… but all prose, definitely prose.

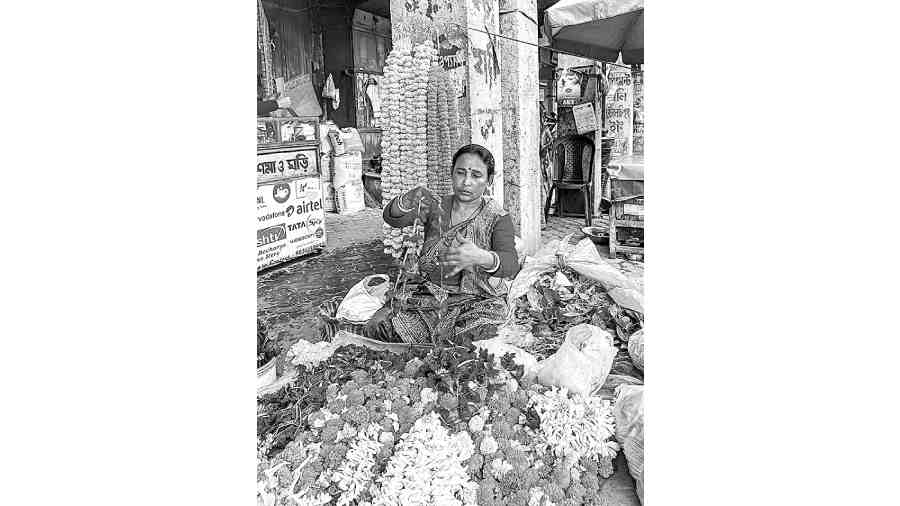

So many flower sellers, but none like her to my mind. Her, in a full-sleeved blouse and synthetic sari wound neatly, pin at shoulder and aanchal tucked at waist, teep, nose pin, earrings, always in place, jet black hair tied back in a neat bun, sitting amidst flowers. Her, of placid expression and limited words, only hands achatter, wandering over her wares constantly, now stitching, now sorting, now giving…

Her workstation is next to a grey column at the entrance to a small bazaar. She has been at this post the last 23 years. I have frequented this market for as many. I have been aware of her existence the last six.

At 8am every day she sets up shop, coming as she does all the way from Thakurnagar in North 24-Parganas, 60 kilometres (by train) from Calcutta. She tells me, “I wake up at 2am, take the 3.12 Bangaon local to Sealdah, and then another train to Tollygunge.” On a regular day she has 20 kilos on her head. Every Thursday, which is designated Lakshmi Puja day in Bengali households, she carries more and has to find a moote or hire a van from the station.

She arrives and the grey column turns golden, from the marigold strings she hangs up. She proceeds to arrange her flowers on a wide low table. Left to right, garlands of akanda, hibiscus, tuberose punctuated with roses, tuberose punctuated with nothing. Far back, bel pata, aam pata, durba ghas. She sits amidst her flowers.

There is a quote attributed to St. Augustine that goes, “If no one asks me, I know what it is.” If you’ve ever been to the market in the morning when she is at her post and then again post-noon when she has left, you will be able to tell what she does to the place just by being.

A nod, a smile, a pleasantry, that’s my regular exchange with her. In all these years I have never asked her name. Her bearing autosuggested “Shakuntala” — it could also have been the bees buzzing around the rajanigandha. At other times, I thought “Radharani” became her, though Bankim’s Radharani who couldn’t sell her mala at rath-er mela was but a girl.

Sometimes when I am exiting the market, I put my bag down next to her stall and catch my breath. And that is how I know she has so many regulars. She scans their faces and appears to know what each wants — 10 garlands on a Tuesday, two garlands every other day... Not that she is never taken aback. She sees the man in kurta-pyjama and a snuff waistcoat and starts to take out something, but he stops her. “Today, I will need a jaba mala with 108 flowers,” he says. Sometimes, as on New Year’s Day, she surprises her clientele by sticking a bunch of red roses in a used bucket of wall paint — a departure from her flower grammar.

Customers come and go. She quotes prices; they pay. When someone haggles, she does whatever she needs to do but with downcast eyes. In her demure disapproval she has the je ne sais quoi of a Raja Ravi Varma subject; had this been a painting it would have been titled — “A Flower seller’s Annoyance”.

She is done selling by noon. On the way back home, she stops at Thakurnagar Market to make purchases for the next day. Then there is outsourcing to do — so and so to make small garlands, so and so to make bigger garlands. It is not as if she does not know how to string a garland. She opens up speckled palms. “From this,” she says and fishes out a long needle.

Talking of needle pricks, getting her to talk about herself is excruciating. Having an element of poetry and being poetic are clearly different things. Our conversation goes like this. Was anyone else in the family in the flower business? “Yes.” Father? “No.” What did he do? “Worked on the farm.” Then who was in this trade? “Ma, didi.” Did they pass on to her some tips of the trade? “No.” But she must have learnt things? “Yes.” From? “Experience.” What kind of learnings? “Fresh produce is important.” Will she pass on these to her daughters? “I have two sons. They are not interested.” Why does she do this? “Abhab... want.” Is this tough work for a woman? “No. Why?”

I need to ask one last thing, for this story — her name. She replies, “There are six of us, sisters. Anima, Sabita, Champa, Iti, Kabita, Bithika.” Then adds, “I am Champa.”

Once upon a time, there was a farm labourer and his wife and they had six girls. They named only one of them after a flower, champa or Magnolia champaca, and she grew up to make a living off blooms.

I told you, some people have an element of poetry about them.