He is one of Britain’s most well-known faces when it comes to the culinary industry. A celebrated chef who has beautifully juggled a successful career as a chef and a television host. Recipient of many awards, this septuagenarian likes “simple food” and has served the likes of Frank Sinatra, Elizabeth Taylor and, of course, the British royal family. He loves French cuisine and when he isn’t in the kitchen, rustling up dishes or consulting, he reads and listens to opera over a glass of wine. Brian Turner — chef, television personality, consultant, author and chef-professor — has had an illustrious career spanning over 50 years.

We caught up with the celebrated chef amidst his busy schedule as a judge at IIHM Young Chef Olympiad, in association with The Telegraph, to talk about wisdom gained and shared, while digging deep into the world of culinary art.

An old picture of Beau-Rivage Palace (above) in Switzerland’s Lausanne, where Turner worked in the early stages of his career

Many of the well-known chefs today have had humble beginnings. You started as a kitchen porter and went on to earn a Michelin Star...

It’s very biblical… if you build on a solid foundation, you can build strong. If you don’t have a solid foundation, you risk a catastrophe of falling apart. Same with life and career. In our industry particularly, you need to go through all the basics, because then you understand what people who work for you are going through and then you can help them from falling in the same pitfalls as you did. I am a great believer in getting young people in the UK trained in cooking and eating right. Then they can build on that in colleges. For most people this is the way to go. There are talented people who just arrive at a stage but at some stage they, too, wish they had the basics to fall back on. In many ways, it’s about the right time, right place, but with the right people training and helping you.

How did you know this was your calling?

If you turn that question the other way around — what would I have done if I hadn’t been a chef? — the answer is, “I have no idea!” I had never thought about anything other than being a cook and a chef. My father had a transport cafe where he used to make breakfast for lorry drivers and factory workers and I just went with him to work. I just stood beside my father and watched him. I smelled, tasted, got that in my blood. So, I have a wonderful foundation from my father.

I was inspired by my father and never really wanted to do anything else. But then I did go to a domestic sciences school. I did catering in college, after which I got an apprenticeship in Simpson’s in the Strand and the best restaurant in the world in those days — the Savoy Grill. I then went to Switzerland, learnt to speak French and worked at Beau-Rivage Palace in Lausanne, which once again was another top hotel in the world. I then worked at Claridges, then this little place called The Capital Hotel and that was part of the real beginning of skill and gastronomy in the United Kingdom. We got a Michelin Star there. And the French didn’t give Michelin Stars to English people back in those days so it was quite unique. And they told us we were quite special. But we weren’t special, we just liked doing what we did.

I ran that for 15 years and then came my own restaurants, my own business and that ran for 15 years… all in one it was a gradual moving forward. I then got involved with young children, colleges and education.

Initially hesitant, a little bit of prodding led to Turner spilling some names like that of the late Frank Sinatra (right), one of the greatest singers of all time, and the late stunner of Hollywood, Elizabeth Taylor (left), when asked about the famous personalities he has cooked for

You got your first Michelin Star in 1974 and that in the culinary industry is considered to be the ultimate recognition. What was the relevance then vs now?

You are quite right and that’s the conception. Personally, I think it’s not as important now as it used to be. What you need to realise is that you need to have people coming through the door and that’s of bigger value than earning a Michelin Star. Having a Michelin Star sets a standard that you have to reach all the time. It can put you under pressure that you can do without. My ethos has always been that I want people coming through the door, smiling, happy and they have a wonderful dinner and say, “That was lovely chef. We will be back,” and they come back. If they don’t come back, you don’t have a business. And if you don’t have a business, you can’t progress and develop your style. It’s about understanding the hospitality business.

Like you had earlier mentioned, there have been instances where restaurants have shut shop, chefs have committed suicide on losing the Michelin Star. What kept you going and aiming for the sky?

The most important thing would be to go back to my father’s cafe. When the big lorry drivers came in and said what they want, you gave them what they wanted. And that whole operation of “what can I do for you”, supplying it and getting thanked for it makes you think you are going to do something again tomorrow. What’s there not to like? And it’s these things that keep you going. In this part of the world, we see that the DNA of people is to share what they have got even if they have a small amount. I remember once that a world-famous footballer had dinner at my restaurant, asked for the bill. We gave him the bill and he went (Turner gestures suggesting that the footballer forgot the wallet) before telling me, “Mr Turner, I am very sorry. I will leave my wife here and go back to the hotel and get my wallet, which I have forgotten.” I told him, “I know who you are and when you get home, write a check.” And he did that! He was such a happy man but was so embarrassed. The most important thing is that they had a good time and that’s what matters.

How did television happen to you?

It’s such a long story! In the early 90s, I did a programme on a battleship that came from Gibraltar and back to England. And we filmed it. Everyone who watched it on television thought it was funny. That got me an invitation to go to This Morning with Richard and Judy (Richard Madeley and Judy Finnigan), where they spoke about our show. There are people who want to work in television and who should work. But for me, if it stops tomorrow, it stops. It’s great for a young man, it’s a great profile. It gets the customers in.

Chefs work behind closed doors. How was it facing the camera for the first time?

Frightening! We, Ainsley Harriot and I, used to do the shows in Birmingham and once the audience came in, they would play things on the big screen for 3,000 people. Until you get on the stage, nerves get to you. It’s hard to start with... it gets easier but never easy. I have made some bloopers.

There’s this programme called It Will be Alright on The Night, and they show pictures of incidences where it went all wrong. They showed a picture from Ready Steady Cook.... This one time when I was about to help a contestant to pipe something out of a piping bag and while piping, the hole was blocked and the bag split, hit me and the co-host. We got cream all over our faces and it was hilarious! And you couldn’t get that choreographed! They show this regularly and I get some pounds. (Laughs)

A lot of budding chefs think that being in this industry is quite a bit about glamour and glitz... that being a chef is “cool”. Do you agree?

There’s a famous phrase that says that we are a victim of our own success. Many chefs, when they get their Michelin Star, feel they can’t take a day off to spend time with their family because if they do, their business won’t run. And I think, we — people at my age and I am one of the oldest chefs at the moment — have a responsibility to watch for young people and make sure that they don’t fall into that trap. Fifteen years ago, all the young people said Jamie Oliver, now they aren’t so sure and I think that we need to just guide them. You need to have inspiration and objective, you have to make sure that it’s not all glitz and glamour.

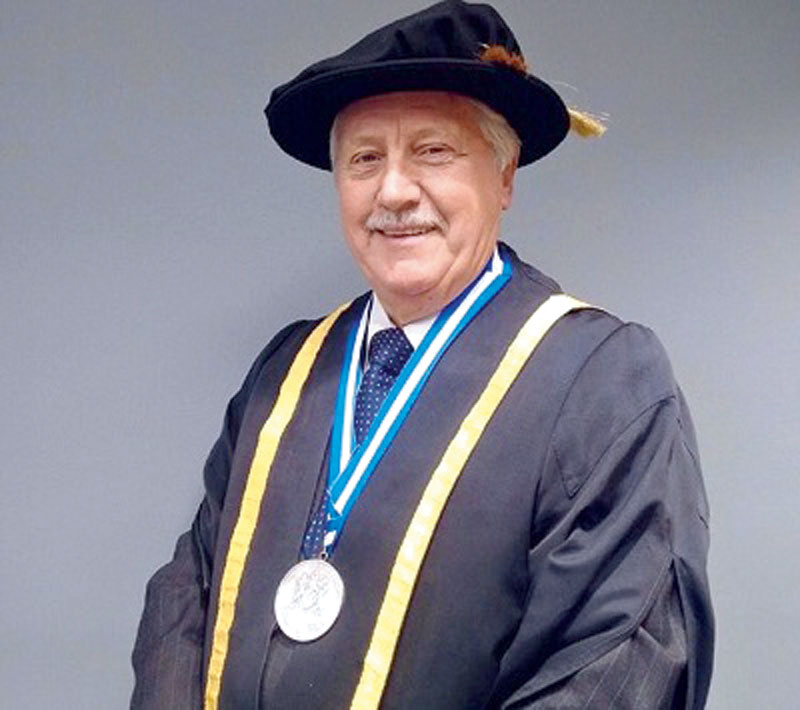

Turner was awarded a CBE — the highest ranking Order of the British Empire — for his service in training in the catering industry and his work as the president of the Royal Academy of Culinary Arts. Courtesy: www.bbc.co.uk

What would be your advice for budding chefs?

The first thing we tell young people is that when you are at the right age, get a part-time job, even if they don’t pay you. Go and see if you can work in a situation where you are called to do breakfast at six in the morning, lunch and dinner until midnight. It may suit you for a week, but will it suit you every week? Can you cope with that? Then there’s the heat, and the hard work... are you physically fit enough to do that for the rest of your life? So, first of all you are going to assess and the only way to do that is to put your foot in the water. Find the best chef near you and request him to give you a job and have the right attitude. You have to understand that a lot of hard work, basics need to be put in to build the future. If you are trying to get to the top too quickly, you aren’t careful and you will fall. And, it’s a long way down.

Who has been your inspiration?

I come from an era where chefs were downstairs people. My father was a great inspiration. Then when I came to London, I went to The Savoy and there was a gentleman in charge of cooking the meat section. He was a mad man but such a talented man. Everything he made was wonderful and how do you learn that? Watch, smell, learn. And then, of course, chefs like Paul Bocuse, Escoffier… they have been inspirational at some stage in our career.

If you have a family, you buy a leg or shoulder of lamb and cook it with all the vegetables and sauces. You can then carve and share the food en famie (with one’s family, in French) rather than just a nice-looking dish. The fussiness is what I have difficulty in understanding. The greatest compliment in my restaurants is when someone asks for a bread and butter to mop up the sauce and they clean the plate, eat it all! For me, that’s the biggest compliment.

Brian Turner

What kind of a chef are you in the kitchen?

I am basically an honest fellow and I like the produce to do the talking. What has sadly happened in the UK, cooking and career-wise, is that we used to get big portions of meat but nowadays everything is small-portioned. If you have a family, you buy a leg or shoulder of lamb and cook it with all the vegetables and sauces. You can then carve and share the food en famie (with one’s family, in French) rather than just a nice-looking dish. The fussiness is what I have difficulty in understanding. The greatest compliment in my restaurants is when someone asks for a bread and butter to mop up the sauce and they clean the plate, eat it all! For me, that’s the biggest compliment.

Is that the danger of less not being more?

I think there’s a great danger of that and we have to be very careful. There are lots of young people who come through very fast, without knowledge of the basics. Really, they don’t understand why something doesn’t work and why it isn’t right. I think it’s our own fault because we have created this. The best chefs for me will always be the best cooks. There are some cooks who make great chefs but they aren’t good cooks. You wouldn’t want them to make your dinner but in terms of organisation of a team and getting people to do things, they are the best. They make sure that it’s cost effective, business is successful. Likewise, you don’t want cooks who are messy all the time, spill things, don’t make it economical to buy. In my opinion, you can’t be a great chef if you aren’t a great cook.

Chefs are known to be passionate and creative. Does getting into the business side of things make the job more mechanical?

Thirty years ago, there were very few who could balance everything. Nowadays, through pain we have learnt that you have to be a good businessman. But once again, the clients don’t come to my restaurant to see an efficient business, they come to eat. I think that we are getting better in that respect. But we have to make sure that young people understand that you need to get back to the business side and get it right, and that’s why you have a business partner. This is one of the good ways to go about it but choosing the business partner isn’t easy.

You are the president at the Royal Academy of Culinary Arts. How are you helping children through your role at the academy?

Approximately 40 years ago, it was called the Club Nine and there were nine chefs who were running their own businesses, just learning and at the end of lunch, every now and then they would drive to one of their restaurants, sit around the table and talk about the problems over a glass of wine. Various problems were spoken about and they would come up with the answers amongst themselves.

Now, we are 350-member strong but it’s pretty much the same thing. We try to help each other out to run our business and restaurant in the correct manner. Having said that, we are far more culinary-based than we are management-based. So, we are about finding young talent and bringing them into the industry, making sure that they are passionate. We need two things, in my opinion, to start with — passion and the right attitude.

The Royal Academy does various other things, like we have a wonderful sustainability programme being built at the moment. We have a scheme called Adopt A School where our chefs go into schools and teach young people, through the ages of six and 12, about eating and understanding food. We have apprenticeship schemes as well. At the end of the day, what we do here is encourage people who come into the industry and ensure that they don’t make the same mistakes that we have.

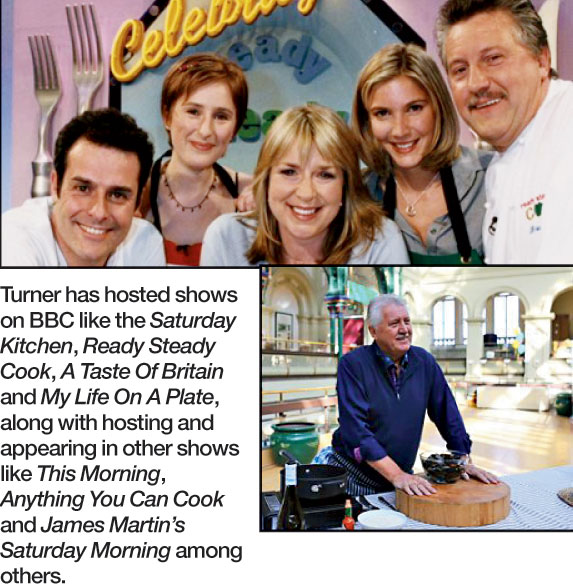

Turner has hosted shows on BBC like the Saturday Kitchen, Ready Steady Cook, A Taste Of Britain and My Life On A Plate, along with hosting and appearing in other shows like This Morning, Anything You Can Cook and James Martin’s Saturday Morning among others. Courtesy: www.bbc.co.uk

You have been awarded with a CBE title — the highest ranking Order of the British Empire. Can you please decode that for us?

What we have is a system, where the monarchy on her birthday, gives awards to people who have gone above and beyond their call of duty in whatever sphere that is. They prefer them to be working people. There are three levels — ODE (Order of the British Empire), MBE (Member of the British Empire) and CBE (Commander of the British Empire). And, I am a Commander of the British Empire and I am very proud of that. It was a recognition of all the work we do in training young people.

What are the changes that you see today in the culinary world vs how it used to be earlier?

The main positives are that chefs have spoken to farmers and producers of meat and they are growing and rearing wonderful products. Suddenly, you go into a restaurant and you are getting quality, sustainable products. Farm to table is one of the main things that’s positive. On the other hand, sadly, we don’t teach people at school, across the nation, how to eat. We are fortunate in our country that we do have enough food, but we don’t teach them to appreciate and understand it. So, there are mixed messages. But for me personally, the fact that once upon a time when you were a chef and wouldn’t be proud, it’s just the other way round now.

How can chefs like you, who are flagbearers of the culinary world, contribute to sustainability?

I have two lovely sons and three beautiful grandchildren and I would hate to think that I have caused problems for their future by adopting the wrong attitude. Sustainability means sustainability of produce, animals but actually the human beings. It’s an essential part of the lifestyle. We have to be sensible people and make sure we aren’t wasting things. Chefs have to sensibly use products. Recycling is important.

What are the culinary trends that you have been noticing recently?

Lots of street food, which cuts the cost. South American food. Then I suspect it would be Vietnam and Cambodia.

One advice that you received which has stayed with you?

Be true to yourself.