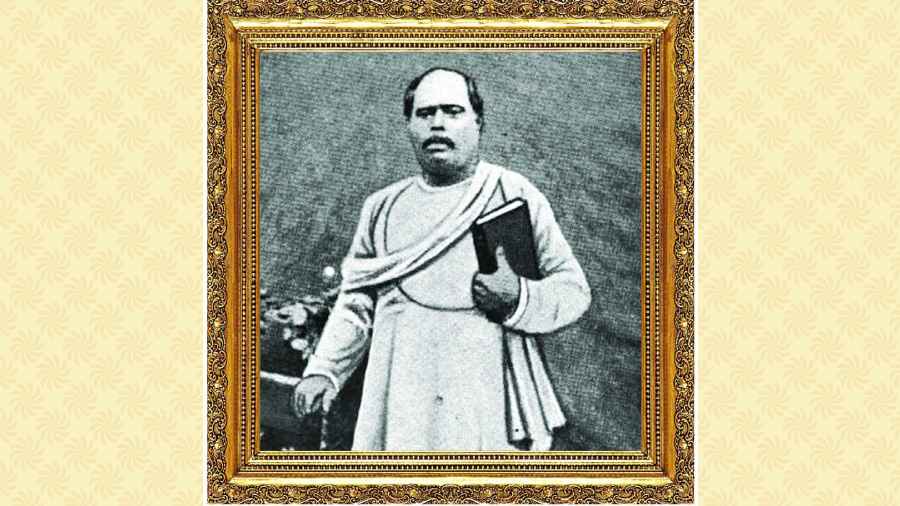

The invitation to the bicentenary celebrations had a grainy photograph of the man being celebrated, serene of face with a thick moustache and some books held close.

Babu Peary Churn Sircar was a proponent of women’s education in India. A contemporary of Ishwarchandra Vidyasagar, he started his career as a schoolteacher, and went on to become the first Indian professor of English at Presidency College, Calcutta. He also wrote a series of textbooks on learning English — First Book of Reading for

Native Children — which generations consulted to learn the language. This includes Rabindranath Tagore and he even mentions it in his autobiographical reminiscences titled Jibansmriti.

“An entire generation of Bengalis learnt the English language and its nuances courtesy Sircar’s First Book — six volumes in all,” says Manimekhla Maiti, the principal

of Peary Charan Girls’ School in north Calcutta’s Machuabazar area. “It is said that Vidyasagar wrote his Barnaparichay (the cult Bengali primer) in consultation with Sircar,” she adds.

Vidyasagar’s name is an indelible part of milestones such as women’s education and widow remarriage. Peary Churn also contributed generously to the widow remarriage fund at a time when most others were reneging on their commitment. Vice-chancellor of Calcutta University Shonali Chakravarti says, “He was a social reformer who espoused the cause of female literacy, a patron of the Eden Hindu Hostel for muffasil boys in Calcutta, a conservative leader of the Temperance Movement against alcohol.”

Peary Churn founded and edited two magazines — Well Wisher and Hitasadhak — wherein he espoused the cause of temperance. He even formed the Calcutta Temperance Society to stop alcohol abuse. These efforts must be read in the context of the Young Bengal Movement, which had moved several young men to believe that drinking alcohol was the mark of being a progressive person. Peary Churn, however, continued to write about the ills of alcoholism as he did about “kaulinya pratha” or the Brahminical custom that allowed an upper-class Hindu man to marry any number of times.

Peary Churn knew that no community could progress if its women remained illiterate. So when his friends Kali Krishna Mitra and Nabin Krishna Mitra of Barasat proposed to set up a girls’ school, Peary Churn stood squarely behind them.

For this, he was socially ostracised, the local zamindar announced a reward on his head and resorted to terror to dissuade the girls from attending school. In the nick of time, educator and Englishman John Bethune intervened in favour of the school. “That was a big morale booster for them,” said Swapan Basu, who was commissioned to write the biography of Peary Churn by the Paschimbanga Bangla Akademi.

Bethune visited the school — Kali Krishna Girls’ High School in Barasat — soon after and was so impressed that he set up what is now known as Bethune School. Sircar did everything to help him. “That included going from door to door, convincing his friends and relations to send their daughters to the school,” writes Basu.

Later, when he came to Calcutta from Barasat, Peary Churn established Chorebagan Girls’ School, the first girls’ school of Calcutta, in 1863. It was later renamed Peary Charan Girls’ High School. The year-long bicentenary celebrations took off at this school on January 23.

Says Maiti, who is also general secretary of the Peary Charan Sarkar Bicentenary Celebration Committee, “We at Peary Charan Girls’ High School shall remember him through various events such as panel discussions, symposiums and souvenirs right through his bicentenary year.”

Peary Churn started work as second teacher at Hooghly Branch School and was eventually transferred to Barasat Branch School. “From inheriting a school that ran from a prison, he transformed it with a new school building, a hostel and then an agricultural school,” says Basu. Thereafter, when he was transferred to Colootola Branch School, he brought it up to the standard of Hindu School, which was in those days the premier school of Calcutta. Noting his excellent work, the British government appointed him assistant professor at Presidency College. Says Basu, “This was somewhat controversial because he did not complete his studies but that was overlooked because of his erudition and teaching style.”

According to Basu, his lectures on (English poet) Samuel Rogers were so popular and his explanation of the allusions in his poetry so good that even his British colleagues asked him how he had worked them out.

But what would endear the Renaissance Man to present times is the story of his exemplary courage as editor of the government magazine Education Gazette. Peary Churn got embroiled in a controversy over a report on a railway accident. While the government tried to absolve itself and played down the number of dead by getting rid of the bodies, Peary Churn did an impartial reporting of the incident in Education Gazette. When he was pulled up for doing as much he immediately put in his resignation.

Says Peary Churn’s great-grandson Amalendoo Kumar Sircar, who lives in California, “I remember reading Vidyasagar’s biography in school. There has not been any such biography of Peary Churn made available to students, though many of their parents and grandparents would have learned English by studying the First Book. Vidyasagar’s statue was vandalised. Fortunately, there is no statue of Peary Churn in any public place.”