In 1922, a 17-year-old set to tune Rabindranath Tagore’s poem Shesh Kheya. He sang it at college functions and other cultural events. When word reached Jorasanko, the Tagore family abode in north Calcutta, the composer was summoned by the poet himself. That day the youth had started to sing and soon enough Tagore slipped into a trance. It was his habit whenever he was writing or composing or when in deep thought. But the young man had no way of knowing any of this. Confused and somewhat awkward at this effect his composition had, he quietly slipped out of the room mid-song.

The young man’s name was Pankaj Kumar Mullick. And these anecdotes and songs punctuated the virtual tribute organised by Intach’s Calcutta chapter and the Pankaj Mullick Music and Art Foundation on May 10 to commemorate the music legend’s 115th birth anniversary.

Mullick’s grandson, Rajib Gupta, did the talking; his wife, Jhinuk, sang a selection of Mullick’s compositions.

Gupta continued, “Dadu met Tagore again 15 years later. By this time he was a music director. He had already worked in films such as Chandidas (1932) and Kapal Kundala (1933) and he needed Gurudev’s permission to use Shesh Kheya in Pramathesh Barua’s film Mukti (1937).” When they met, Tagore inquired softly, “Why did you run away the last time we met?”

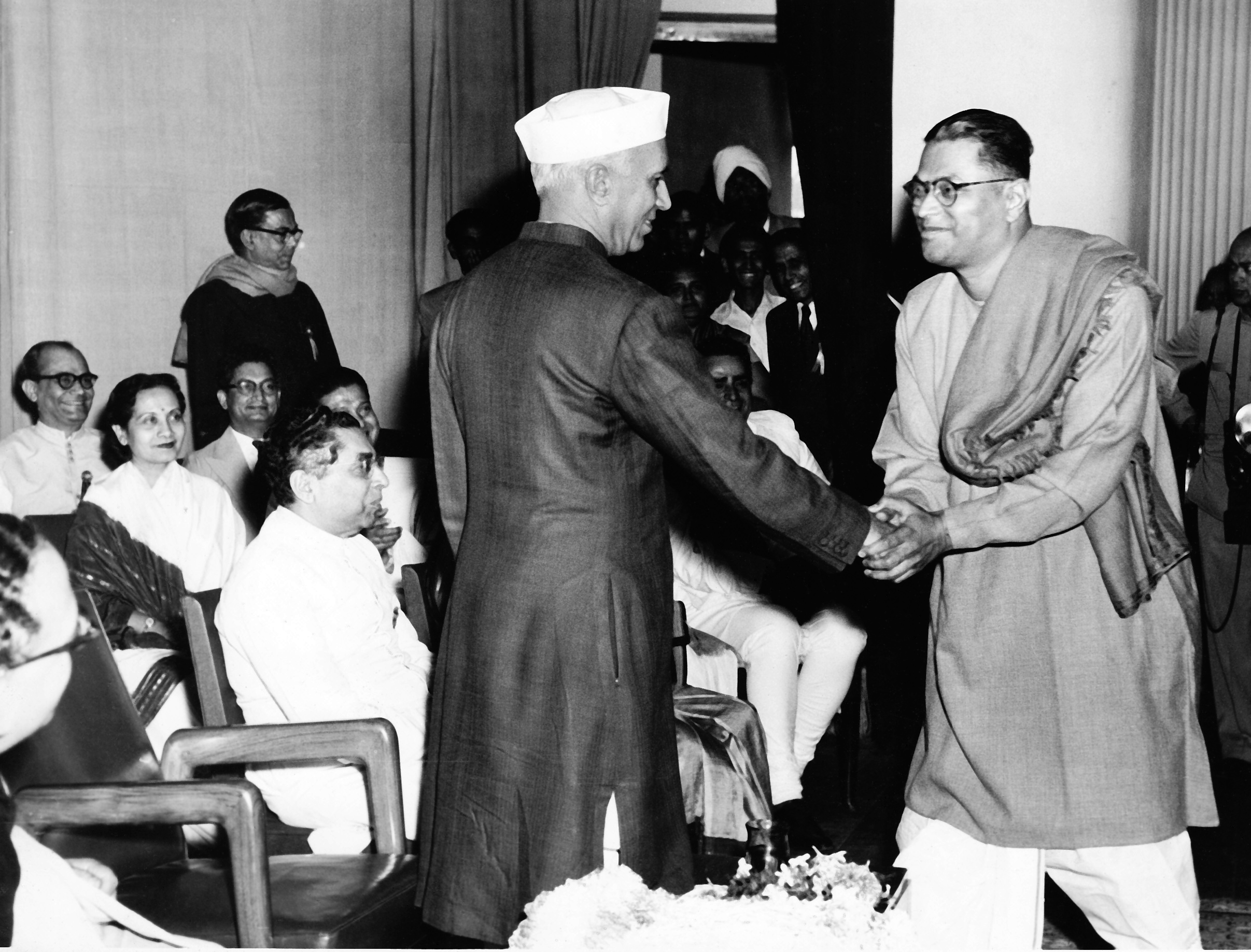

Melody maker: Pankaj Mullick; with Jawaharlal Nehru in 1955 at a seminar Courtesy, Rajib Gupta

This time, Tagore heard the entire song and was overwhelmed. He granted Mullick permission to use the song. Should you run a YouTube search, the scene will surface on your screen. The silver waters, empty, but for a single vessel. The horizon, obviously flushed even in a black-and-white print, with the coconut palm leaning against it. And the sun dipping low into the river. The song is picturised on Mullick — it was his debut as an actor — but it is his voice more than his screen presence that can hold audiences across generations captive. The lines go — Diner sheshe ghumer deshe ghomta pora oi chaya/Bhulalo re bhulalo mor pran/O parete sonar kule andharmule kon maya/Geye gelo kaj bhangano gaan… At day-end in the land of slumber, a veiled shadow/Casts on me a spell sublime/On the other side, by the golden shore, lives what credo?/It pierces all worldly chores with a melody divine.

Insistent though neither plaintive nor resigned, Mullick’s music and rendition add another dimension to Tagore’s words.

Mukti is a tumultuous relationship saga. In the end, the man dies and the estranged wife survives. When Mullick narrated the script to Tagore, the elder apparently remarked, “It seems the protagonist of your story is in search of mukti... freedom.”

When Barua learnt about this exchange, he promptly christened his production Mukti.

Pankaj Mullick in the 1937 film, Mukti, with Pramathesh Barua Courtesy, Rajib Gupta

Rajib does not tell a linear tale. He does not need to. His memory drive is teeming with gems and he can pick and choose, polish and cast aside as he pleases. The cast from his anecdotes is delightfully star-studded.

He talks about the camaraderie between Mullick and singer-actor-superstar K.L. Saigal.

Saigal acted in a couple of Bengali films produced by New Theatres. In one such, he was required to sing a Rabindrasangeet — Tomar binay gaan chhilo. But there was a slight problem — Saigal didn’t speak any Bengali. Those days not only was it uncommon to have a “non-Bengali” sing Rabindrasangeet, culture vigilantes too were not entirely encouraging. The way out was to have Saigal copy Mullick “pronunciation by pronunciation, timbre by timbre”. Rajib’s narration trails off and Jhinuk strategically breaks into song.

Next comes the tale of Mullick wanting to have the Calcutta Philharmonic Orchestra play to his rendition of yet another Rabindrasangeet, Pran chay chokkhu na chay, and the keepers

of tradition refusing to have any of it. By this time Tagore had passed away. Finally, Mullick did a Hindi translation and thus was born the popular Pran chahe nayan na chahe. Jhinuk breaks into song again.

Sepia-tinted times are not free of complexities. Mullick joined New Theatres around the same time as the famed composer, Raichand Boral, in 1931. The two worked as joint music directors for six years. Despite the collaboration, as Rajib points out, a lot of their films did not have Mullick’s name in the final list of credits. It seems Mullick, who was at that time the breadwinner of a joint family of 60, did not wish to jeopardise his position by picking a quarrel with the studio bosses. But the old wound obviously was never quite forgotten. It merely turned into one of those legacy aches that will roll from generation to generation.

After Mukti, Mullick was set free from a spell of ignominy. He learnt Rabindrasangeet, sang them on the Broadcasting Company Ltd, the colonial predecessor of the All India Radio (AIR), and was the first to use them in films. “Dadu had the songs translated into several Indian languages including Hindi, Gujarati, Tamil and Telugu,” says Rajib, whose narration picks up pace and one can almost sense the busy hum from Mullick’s heyday.

The rundown in no particular order. Helming the popular radio programme, Sangeet Shikkhar Ashar, for 47 years. Being honorary advisor to the folk entertainment section of the government of West Bengal, appointed by chief minister Bidhan Chandra Ray himself. Travelling across India with a variety of productions showcasing Bengal’s folk heritage. Composing Mahishasuramardini.

Member of the Calcutta Municipal Corporation’s mayor-in-council, Debashish Kumar, joins the virtual adda and elaborates on Mahishasuramardini — the programme aired by the Broadcasting Company Ltd at the crack of dawn on Mahalaya.

Mahisasuramardini had more than one creator. There was playwright Bani Kumar, who had scripted it all; Birendra Krishna Bhadra, who did the Chandipath, or invocation of the goddess, and was also the compere; and Pankaj Mullick, who set it all to tune.

Rajib does not forget to mention how one year it was ditched for a programme by Mullick’s protégé Hemanta Mukhopadhyay. He says with restrained pride, “But there was a public uproar and the broadcasters were forced to air the original thereafter, year upon year, beginning with that very year on the day of Mahasashthi.”

Rajib’s narration changes tack when he talks about his grandfather’s work in films. The 1930s spool rolls. Heady years. After a character role in Mukti, the lead role in Aandhi (1940). Thereafter, Doctor the same year. Rajib keeps it real, quotes Tapan Sinha who is believed to have said, “Pankaj Mullick was a decent actor.”

The actual glory, the out-of-the-ordinary stories, have to do with Mullick’s career as composer. How O.P. Nayyar said to Ameen Sayani that as a six-year-old he was inspired by New Theatre’s Pankaj Mullick to take up singing. How Mullick introduced playback singing in Indian films. How he introduced Western musical elements in popular Indian music — fundamentals of harmonisation, interlude music, counter melody. He discovered the horse-beat rhythm, the train rhythm. “You know A.R. Rahman’s Chhaiyaan chhaiyaan? That train rhythm Dadu was the first to use in Doctor.”

And the legacy chugs along…