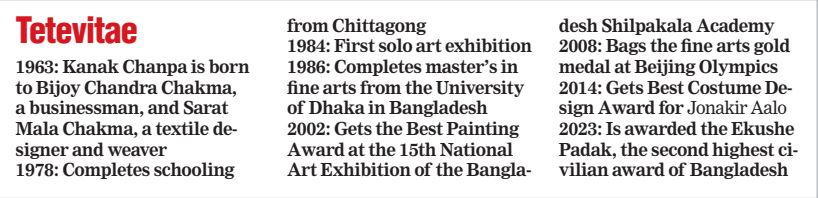

Through my work I have always tried to represent the Chakmas, their lifestyle, their struggles, their pains,” says Kanak Chanpa Chakma in a zoom call from the Dhanmondi neighbourhood in Dhaka. Kanak Chanpa, 59, is a Bangladeshi artist from the Chakma community; this year she was awarded Bangladesh’s prestigious Ekushe Padak for her work.

In the laptop rectangle, I can see a slice of a living room and a loaded bookshelf. There are a couple of Buddhas in it. The Chakmas, a hill tribe long settled in the Chittagong Hill Tracts of Bangladesh — and also in India and Myanmar — follow the Buddhist faith. There are over five lakh Chakmas in Bangladesh. The India number is around 2,50,000.

Kanak Chanpa was born and brought up in Tabalchari village in Rangamati, a hilly town in southern Bangladesh. She says, “It was a small village full of greenery. I spent many hours sitting by the Karnaphuli river there. The colours in my painting come from what I saw.”

In bold colours she paints the landscape of her childhood memories. She continues, “Land, agricultural land, habitable land is one of the major issues of the Chakma tribe.” She goes on, “I am not a politician and I will not dabble in politics. My paintings are a silent protest against the manner in which the issues of our hill tract have been treated.”

She recounts how the Chakmas’ original habitation was somewhere in the plains where agricultural land was in abundance. “But when the dams were constructed, the plains got flooded and we were forced to climb up the hill. We lost a considerable portion of land.” The artist is referring to the huge power development project in the Chittagong Hill Tracts and the construction of the Kaptai dam in the late 1950s.

Kanak Chanpa’s canvases throb with her isms and her ism colours her artistry. Even within the framework of a Chakma narrative, again and again she uses her brush to highlight the story of the Chakma woman. The conversation keeps turning from artist to art and back. Kanak Chanpa talks about her own mother, recently deceased, how she worked alongside her father in the fields they owned, did all the domestic chores and then worked on the loom. “But despite all, she was never consulted at the time of decision-making; only male members were allowed to express their opinions,” says the daughter. She admits she didn’t understand this arrangement as a girl, and now as a grown woman, it makes her angry in retrospect.

Kanak Chanpa does not want to be stuck doing the same thing over and over again. She tells The Telegraph, “I want to look beyond my own tribe. Bangladesh has 50 listed tribal communities. These are slowly losing their identity. I want to hold them up to the world.”

Some years ago, she was entrusted with a project by the Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy that required her and a congregation of artists to travel to tribal areas such as Rajshahi, Netrokona, Dinajpur, study the different tribal art forms and then put together an exhibition.

Has she been to Birbhum in Bengal? Turns out she has. “The Santals of Birbhum are aware of their culture. In India, they are in the limelight. I want to do the same for the tribes in my country. The more I paint them, the more visible they will be.”

Kanak Chanpa remembers how during a visit to northern Bangladesh, she had asked a tribal woman to show her the traditional ornaments. But the woman had nothing to show. “We could not find traditional ornaments of the Koch, Rajuar, Rajbanshi, Oraon and Santal tribes of that region. They wear jewellery made of plastic beads,” she says.

Bringing the tribal people to the forefront is just one thing on Kanak Chanpa’s agenda. In 2018, she rolled out scholarships for tribal students who want to make a career in the arts. She is also the founder president of the Ethnic Artist Foundation which supports indigenous artists. She is a founder member of a women artists’ association in Bangladesh.

Kanak Chanpa is happy that the government of Bangladesh has started recognising tribal languages. She says, “The government has already introduced five tribal languages in primary schools as the medium of instruction — Chakma, Marma, Kokborok, Garo, Santali. So tribal children will study in their mother languages up to Class V and then shift to Bangla. This will be done for all the other tribal languages. Work is in progress.”