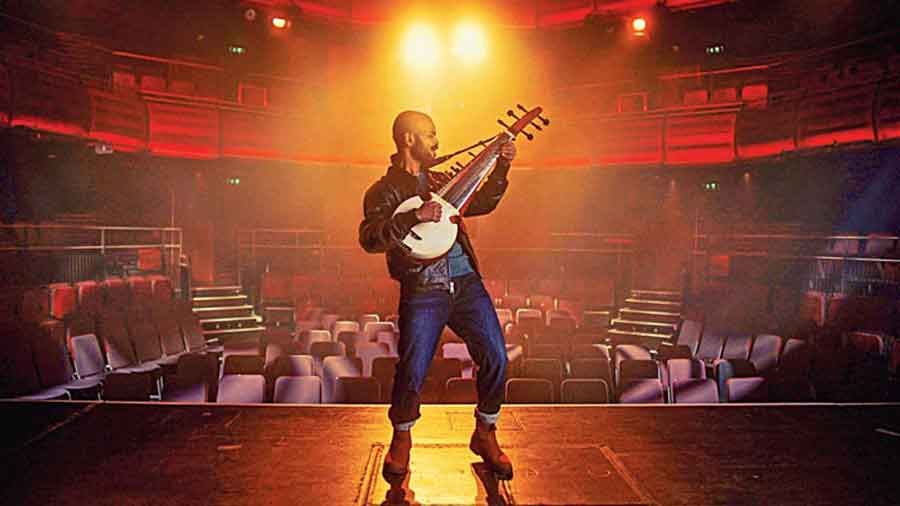

Leave him alone with the sarod and he will come up with something colourful, vibrant and magical. Give him the stage and he will own it.

Offer him food for thought and he will give you a rush of unforgettable visuals. London-based Soumik Datta is a multifaceted artiste who has performed at iconic venues with equally iconic artistes — Jay Z, Beyonce Anoushka Shankar, Joss Stone and Nitin Sawhney, to name a few.

He has two exciting new projects — Songs of the Earth and Silent Spaces. He has been awarded a British Council climate change COP26 creative commission, and his project, Songs of the Earth, will be presented in the run up to the 26th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) in Glasgow in November. And the early part of 2021 saw Soumik join a diverse team of British Asian, black and ethnic minority musicians and dancers to create a six-part, visual album called Silent Spaces.

For him, “art doesn’t need to be a race”, so he is working at his pace and on projects that make him feel content. Here’s more from the man.

Songs of the Earth and Silent Spaces. What were the starting points for these projects?

My music and art projects have always reflected the questions that troubled me. Be it issues about representation, injustice or the climate crisis, I’ve always found the space of discomfort and confusion to be a deep source for creative dialogue.

Increasingly we are living in a world that is polarised, filled with the outcries of marginalised voices now amplified on social media. So the intention behind every project is to try and untangle the impossible — to catalogue chaos through creativity.

Silent Spaces was an attempt to make sense of the new world we witnessed during the pandemic. Songs of The Earth seeks to create a new music and animation film in alignment with the UN climate conference COP26.

Since Songs of the Earth also involves illustrators Anjali Kamath and Sachin Bhatt, was there a need to conceive the project differently to incorporate the graphic element?

I’m writing, scoring and directing Songs of The Earth — an animated short film commissioned by British Council for COP26. We’re treating it like any other film. I had to first write an original story that grew out of conversations with environmental leaders and our partners, Earth Day Network. Sachin and Anjali, both in India, then fleshed out my narrative through brilliant illustration and animation. I’m currently composing the music in London.

The hope is to make a beautiful, emotional dreamscape of a film that speaks to young people all over the world, sparking courage, acts of change and future interventions.

Is there a message in the six-part visual album Silent Spaces?

During the pandemic, I wanted to revisit some of UK’s most iconic culture buildings which, bereft of audiences or shows had fallen eerily silent. But Silent Spaces wasn’t just about reawakening museums, nightclubs and concert halls. It was also about the breaking of societal silences.

After the killing of George Floyd which sent ripples through the planet — I’ve become acutely aware of my sense of privilege, the burden of colour and the uncomfortable truth of how many of us are complicit in contributing to a society that supports racial inequality — a conditioning we now urgently have to rewire and rewrite through collaboration and self-education, building bridges between people of different ethnicities. At its heart, this was what Silent Spaces was about — a coming together of black, Asian and diverse artists as a model of societal unity.

Much has happened since your BBC travelogue series Rhythms of India. With pandemic restrictions easing in the UK, are you preparing for concerts? Artistically, have you come out stronger from the pandemic?

I’d love to say that I’m stronger now than before — to chirp on about how much the pandemic has taught me. But the truth is far less of a headline. Somewhere between the pursuit of creativity, rapid self-education and a close encounter with isolation — the only thing I feel is a state of flux. At the moment I’m just trying to anchor my feet while not being apathetic to the world around me. It’s hard. We’ve all been numbed by the battering ram of countless stories of injustice from the West Bank to Minneapolis. And to see India lit by the pyres of those denied oxygen was heartbreaking.

I cherish older memories when I travelled across my motherland filming Rhythms of India for BBC, visiting villages and towns from Kerala to Rajasthan. Little did I know that I would be away for so long, so soon after.

Do you see a new phase for young Indian artistes living in the UK, a phase that goes beyond what we saw in the 1990s, of pairing Indian instruments and electronic beats?Also, playing Indian classical music in the UK may lead to getting stereotyped. The audience may have a homogeneous perspective to the music. Have you faced such a situation and how do you overcome it?

The current generation of Indian musicians and dancers in the UK have a lot to offer. They are interested in dialogue, experimentation, community and are increasingly unashamed to use their voice as a vehicle for change. In the 1990s artistes were focused on the ‘what’.

Now I feel a real sense of the ‘why’ taking centre stage. As an artiste if you can answer — Why do I sing? Why do I dance? Why do I create? — you can reach a place of tremendous clarity and empowerment.

At times, it feels like there’s pressure on musicians to make it to streaming service playlists and make music that sounds good on wireless earbuds and headphones. What has a musician of your stature — one who thrives in live settings — has to offer an audience that’s growing up buying earbuds and headphones?

With streaming on the rise, it’s undeniable that music is now being primarily consumed through digital portals forcing many artists to learn and adapt to the changing technology. This is especially difficult for independent musicians trying to keep up with the tech teams behind the success of other signed artistes. At its heart, it’s competitive that is the source of the crisis.

But art doesn’t need to be a race. And perhaps with the winds of change, comes an invitation to improve and upgrade the way we work — not competitively but collaboratively, forming knowledge hubs between multi-disciplined individuals (musicians, dancers, film-makers, marketing experts, app builders) where collective benefit outweighs singular gain.

My production company, Soumik Datta Arts is currently prototyping this concept. And I’m hoping to open it up to people in India soon.

When does India get to see a Soumik Datta concert?

This year I’m excited to have signed with one of the world’s leading agencies, United Talent. We’re in the process of building a new band and figuring out what touring looks like post-Covid and post-Brexit. To say I miss India would be a colossal understatement. I miss the air. I miss the noise and the sound of my mother tongue. Really, I can’t wait to play at festivals and for audiences there as soon as it’s safely possible.