On a fine spring day in London in April 2009, when the daffodils, cherry blossoms and magnolia were in full bloom, Soumitra Chatterjee, who had come to the UK for treatment, opened up, probably like never before.

What was engaging was the way he spoke of his love of life in an exclusive interview with The Telegraph.

Soumitra, who was staying with friends in North London, admitted his diet was a bit restricted. But, speaking in a mixture of Bengali and English, he said he would “quite like to fit in a nice, juicy steak with some excellent red wine — prochur wine khabo, prochur (I shall drink lots of wine, lots)”.

“Time is very precious, it has become shorter now, I can almost see the end,” he observed.

“The end is inevitable, you know,” he said. “It is useless to be afraid of it. I am only afraid of physical pain and nothing else. I wonder if at the end I will be able to preserve my dignity. I don’t want to lose my dignity even when I am going away.”

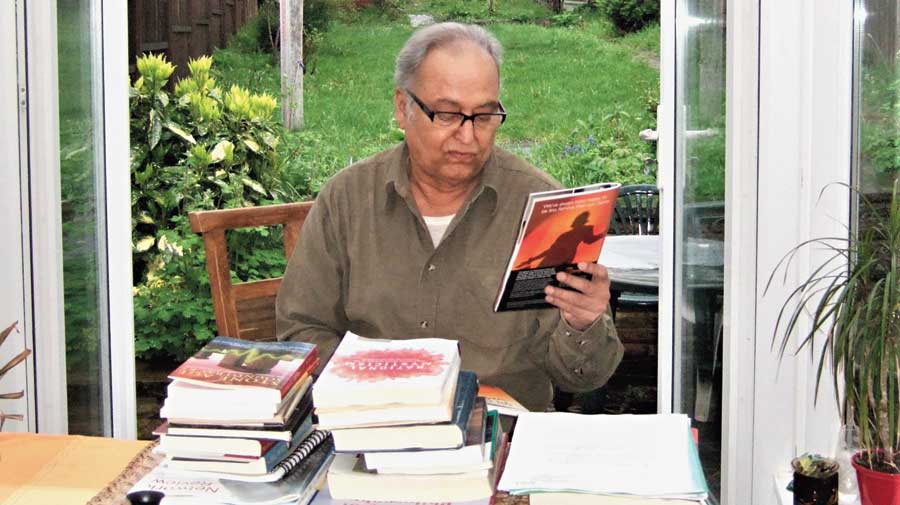

Soumitra Chatterjee soaks in a fine spring day in London in April 2009, amid cherry blossoms and magnolia in full bloom. Amit Roy

He spoke of the resilience of the human spirit. “By and large, I am ok. No one wants to die. I don’t either but I have learnt to accept that it will come. At some point, life transforms itself into death.”

In over a month in London he had managed to fit in daily walks, some sightseeing (a trip to Yorkshire), catch up at home with DVDs (Il Postino, an Italian movie; Behind the Sun, from Brazil; the Czech film Kolya; and The Lives of Others) and take in a play at the National Theatre, Death and the King’s Horsemen, by the Nigerian Wole Soyinka.

He laughed when asked if fans knew the real Soumitra Chatterjee?

“They have their image of me but that may not essentially be me. But I have a question, too, ‘Do I know myself so well?’”

Asked how he would like to be remembered, he replied: “Maybe I have been of use to some people on their journey through life. They may have seen one of my movies and (felt), ‘I can fight again.’ I get a lot of letters.”

The man who made his film debut as Apurba Kumar Roy in Apur Sansar conceded that “it is difficult to go on after you have started your life with a double century. But when you have geniuses like Bradman you have enough inspiration to continue with your creative efforts.”

He explained his decision not to defect to the Hindi film industry: “There are executives in Calcutta who earn more than me. But to go to Bombay would have meant reorienting my mind which was not possible for me.”

He had seen Pather Panchali 30-40 times. In common with another of his favourites, Vittorio De Sica’s The Bicycle Thief, made in 1948, “they are classics. They transcend time. People will see them as long as there is cinema.”

“As a student of cinema, Pather Panchali is the weakest of Satyajit Ray’s films. It is the second, Aparajito, which is technically perfect. But Pather Panchali has such vitality and life force that I have not seen a human unaffected by it.”

Soumitra Chatterjee soaks in a fine spring day in London in April 2009, amid cherry blossoms and magnolia in full bloom. Amit Roy

If he could take only a handful of films to a mythical desert island from which there was no escape, he could settle for Pather Panchali and Charulata. His life would also not be worth living unless he could take Charlie Chaplin’s 1925 movie, The Gold Rush, as well.

As he played a little piano, he revealed his pick of Western classical music would include Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons and Beethoven’s Choral Symphony.

He estimated he had read 8,000 books in his time. His choice for a desert island would be the Mahabharat. He enjoyed contemporary Indian writers in English, and his favourite was Amitav Ghosh, especially The Glass Palace and The Hungry Tide. “It is written in very competent English but I feel it is a part of Bengali literature.”

In light of his passing it is worth recalling that Britain’s most distinguished film critic, Derek Malcolm, himself now 88 — no one did more to promote the then relatively unknown Satyajit Ray after the success of Pather Panchali in Cannes in 1956 — took every opportunity to draw attention to Charulata, his favourite Ray movie.

When the British Film Institute held a Ray season from August 14-October 5, 2013, Malcolm urged his readers to make a point of seeing Charulata: “No director has bridged the gap between the cultures of East and West as convincingly as the Bengali filmmaker Satyajit Ray. And no film has done it quite so thoroughly as his 1964 masterpiece, Charulata, which is being given an extended run at the BFI Southbank.

“The interplay between the always understated sophistication and its utter simplicity of expression is what makes the film so substantial. That and the performances of Madhabi Mukherjee and Soumitra Chatterjee (who acted in 14 of Ray’s films) as Charu and Amal.”

In London, those who knew “Soumitrada” well includes Sangeeta Datta, who said: “He was my first choice to play the lead (opposite Sharmila Tagore) in my feature Life Goes On, an adaptation of King Lear. He had to drop out reluctantly…. He is part of my docudrama on Rituparno Ghosh, for which he came home and did a long interview. He also read excerpts from Rituparno’s First Person — these readings were the spine of the film. We had planned a long interview to mark Ray’s centenary this winter. Covid changed all that.”

Soumitra was critically ill when Sangeeta was leaving Calcutta but had passed away when her flight landed in London on Sunday.

“Soumitrada has been an intrinsic part of the city of Calcutta,” said Sangeeta, adding: “Soumitrada was versatile doing theatre, debates and chess. My mother, who was a few years junior to him, recalls his magnetic presence as he held forth with poetry and politics in the famed Coffee House on College Street.”

This is also borne out by Krishna Dutta, London-based author of Calcutta: A Cultural and Literary History. Soumitra came to her home in London for dinner and she remembers meeting the actor when he accompanied his daughter Poulami for a production of his Bengali play, Homapakhi.

She said that especially for the Bengali diaspora in London and elsewhere, Soumitra was Calcutta and Calcutta was Soumitra.

“I mourn Soumitra,” said Krishna. “Throughout his varied acting career he was a kind, genuine and proper Bengali gentleman. Intellectually curious, decent, artistic, sensitive, mild-mannered and good with Bengali diction. He had deep respect for the best of Bengal’s heritage and loved the ambiance of Calcutta with warts n’ all and never felt tempted to leave the city. He will live on forever through the films of Satyajit Ray.”

In reporting the death of the “India acting legend”, the BBC quoted the late Marie Seton, author of Portrait of a Director: Satyajit Ray, who said of Soumitra: “His chief asset was the natural sensitivity of his appearance.”