Just when the skies begin to turn from powder blue to inky, he arrives at the intersection of Bentinck Street and Waterloo Street in the hub of central Calcutta. Him in a white pyjama and kurta, with what looks like an odd-shaped harmonium case on his back.

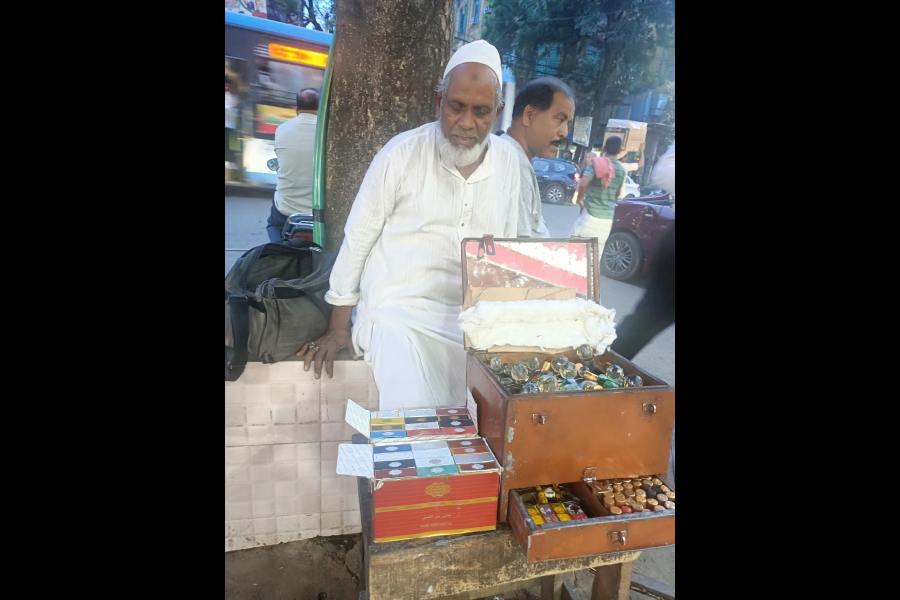

Behind him is a biryani and kebab shop. On the other side, the car washers are swinging their buckets. The streetlights have just come on and the shops are aglow too; the water accumulated in the pitted road makes for a shimmering mirror. In the midst of it all, Mohammad Jafeer Khan fishes out a stool, places his odd box on it and then throws open the lid.

Almost immediately, a thick sweet scent emanates from it. It drowns the smell of the phenyl just poured over the pavement, possibly to make a killing of the mosquitoes. It is Friday; from out of nowhere people start to queue up before Khan’s surma and ittar corner.

The 58-year-old works fast, his practiced fingers apply surma or kohl to one customer after another, men and boys. One of them is Rahul Akhtar, a 20-year-old student. At first contact with the surma, his eyes fill up with tears. Khan says, “No matter how big and beautiful a house you build, no matter how sturdy its door, dirt will enter. Similarly, our eyes are exposed to a lot of dirt and grime throughout the day. There are dust particles that need to be removed. That is what surma does. It cleanses your eyes.”

Mohammad Jafeer Khan ittarwala. Moumita Chaudhuri

At this point the sound of the azan floats out of the neighbouring Tipu Sultan Mosque. Immediately, Khan gives the younger man’s eyes a hasty rub with his yellow handkerchief, pockets a ten-rupee note from him and leaves for his evening namaz with his “shop” in the care of his pavement peers.

On a fair day, Khan earns Rs 250-300 and then suddenly, someone might come along and buy a bottle of expensive ittar — indigenous perfume — something priced at Rs 200, and he is ready to pack up.

Khan’s box is a wondrous thing. Beneath all those bottles, some with golden caps and others fitted with octagonal glass heads, are compartments and compartments. One such is packed with unopened boxes of ittar with curious labels scrawled over with names such as WhatsApp, Dark Chocolate, Sultan, Black Oudh, Jasmine... A thin drawer opens out from one side and reveals neatly arranged glass vials, these are half-filled ittar bottles. Khan sometimes dips a wick of cotton wool into one for a customer to tuck behind the ear or apply on the wrist. In the adjoining compartment is an array of tools — long black sticks used to apply the surma.

Evening prayers done, Khan starts to tell his story. He tells a disorderly, threadbare one, the chunk of it in monosyllables. He is from Bihar’s Madhubani district. His father died when he was a child. His mother raised him and his five siblings. He attended a madrasa for a few years.

There is a lull in business for a bit, so Khan fetches tea.

He continues, “When I was still a teenager, I decided to come to Calcutta with a fellow villager. I had heard from them this is a big city with many opportunities.” The last four decades, Khan has been living in different rented rooms in New Market. Every three or four months he goes home to Madhubani. Two burqa-clad women interrupt the conversation. One of them is looking for a specific ittar. She shows Khan a visual on her smartphone. He nods and asks her to come back after a week.

Khan started out doing the dishes in an eatery in central Calcutta. “I would do any odd job that came my way. I did not have a specific aim in mind. I was not looking to specialise,” he says.

An elderly man whom he appears to know comes up to exchange pleasantries. “Kaam waam theek chal raha hai na?” That’s it; he doesn’t want any surma. “It burns,” says the elder.

So how did he come to sell ittar? “By chance,” he replies. “I started my shop three decades ago. I had no experience but I had seen some others sell ittar and surma to people on Jumma day. You do not need any training to learn this art,” he adds. A man stops before Khan, points to a packet of ittar, hands him a fifty-rupee note and leaves hurriedly.

Khan made enquiries, figured out where to procure his material from, Ezra Street, Burrabazar — from the Marwaris. He pats his box, “I designed this thing according to my convenience. But this is not my first.”

Is this a profitable business? He says, “It used to be. Three decades ago, it was a thriving business. It was considered to be a style statement by itself and everyone would want to put surma in their eyes. Even women would come to my stall.”

It seems there are very few people who have any use for such traditions these days. “They do not know about the medicinal value of surma. It prevents eyes from stress and strain. It improves visibility...” he goes on and on.

This is not his only corner. Khan sets up shop in different spots across central and north Calcutta — in front of Nakhoda Masjid, Calcutta Medical College, Shyambazar, Hatibagan. Sometimes he goes right up to Behala in the southwest or Dhulagarh in Howrah, where his customers are the zari workers. Khan says his wanderings are not for profit, “Ittar to ek bahana hai.” So what is he in it for? His reply — “Bas, mil-milna ho jata hai.”

On the scent of kinships.