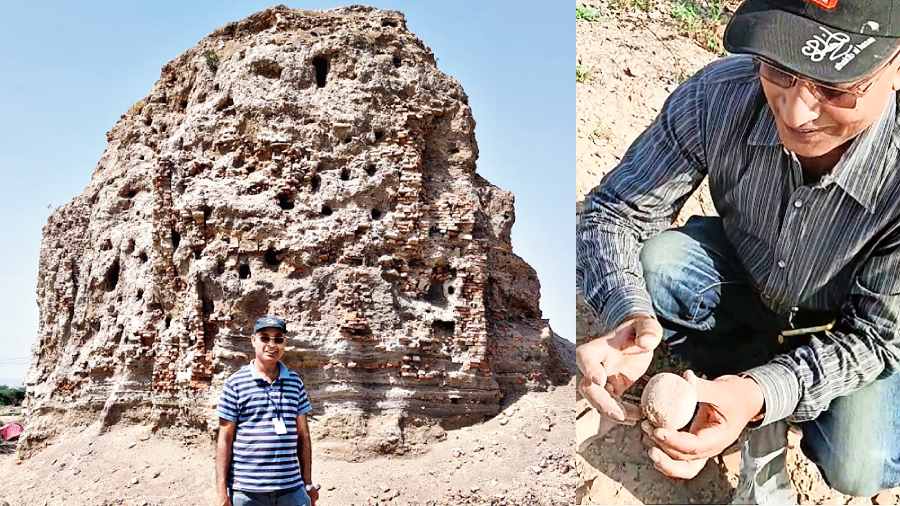

Sandipani Dipan Bhattacharya had rushed all the way from New Delhi to Harnaul village in Haryana, 200 kilometres away, on a summer afternoon. An amateur archaeologist and a former government officer who now works as a corporate director of a private company, Bhattacharya was chasing a tip-off that some farmers were breaking down what appeared to be the ruins of a 3,000-year-old civilisation. The dig threw up potsherds and terracotta figures buried for at least a couple of millennia. The artefacts were being discarded by the farmers, and suspicious agents — possibly antique peddlers — could be seen in the area.

By the time Bhattacharya reached the site, an excavator machine was in action. As he ventured into the vandalised mound, he found fragments of exquisitely painted pottery and shards of animal figurines — unmistakable remains of a prehistoric culture.

The village was not very far from Rakhigarhi, an archaeological site from the bronze-age Harappan culture or the Indus Valley Civilisation in Haryana’s Hisar district. Located in the erstwhile Ghaggar Hakra river plain, Rakhigarhi is 30 kilometres away from Ghaggar, a river that comes alive during the monsoons and is called Hakra downstream in Pakistan.

The site, according to archaeologists, is believed to have thrived between 2600 and 1900 BCE and gradually declined when the river died. Some scholars claim the river could be the remains of the Saraswati mentioned in the Rig Veda.

But Harnaul, where the archaeologist had landed, was not marked as a Harappan site by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). “It was an extension of the homestead of a farmer, oblivious of the ruins of any prehistoric civilisation beneath his ancestral property,” says Bhattacharya. The archaeologist found several samples of antiquities there. After his return, he informed the state archaeology department as well as the circle incharge of ASI about the finds.

This was not the first time he had witnessed such damage and desecration of ancient ruins. In some cases, identification and demarcation as “protected sites” by ASI have failed to prevent damages or encroachments by locals. Some experts claim Rakhigarhi was the largest site from Harappan culture, perhaps larger than Mohenjodaro discovered 100 years ago.

But current archaeological sites may not reflect the exact area or the boundaries of an extinct civilisation. According to Bhattacharya, several cultures across an extensive area merged with the civilisation and numerous rivers, streams and channels aided their growth. In India, there are a number of sites along paleo-channels, which were streams at that time but dried up or were diverted over time, such as Ghaggar-Hakra, Beas (Punjab), Hindon (Uttar Pradesh) and so on. “We don’t know how much of Rakhigarhi has already been damaged because the area is thickly populated and no large-scale archaeological excavation has been carried out yet,” he adds. Although excavation is currently on, many of the sites have already been damaged by nature as well as human activities.

Bhattacharya has travelled extensively in areas in the erstwhile doab regions of the extinct river valleys and discovered a wide range of artefacts in the wild. When farmers till the soil or dig the mounds, the innards throw up a variety of antiquities. In Igrah (Jind), he saw a little girl playing with an animal figurine she had picked up in a tilled agricultural field. The “toy” — she had happily given it away to the archaeologist — turned out to be a relic from the late Harappan period. In Chhang (Bhiwani), he discovered prehistoric stones used in weighing scales. He found fragments of ornaments made of faience — glazed pottery similar to glass — in Tigrana (Bhiwani). Such tin-glazed earthenware represents the advanced technology of Harappans.

Bhattacharya has been collecting artefacts, preserving and donating them to researchers. Recently, he gave away a cache to Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University in Purulia in Bengal. Sonali Banerjee, who teaches there says, “We received 10 artefacts, which include potsherds of Hakra Ware culture (3300 -2800 BCE) of southwest Harappa.” Bhattacharya’s own research has recently culminated in a Bengali book titled Sindhu Sabhyatar Agnipuja o Vaidik Yagna or Fire Worship and Ritual Vedic Sacrifice of Indus Valley Civilisation.

Ravindra Singh Bisht, a former joint director of ASI who specialises in the study of Indus Valley Civilisation, is appreciative of Bhattacharya’s efforts to protect the ancient legacy. During his tenure at ASI in the 1970s and later, many of the mounds of Harappan civilisation in the area were declared “protected monuments”. He says, “Some mounds are so thickly populated that bringing them under protection or carrying any excavation is extremely difficult.”

Bhattacharya has been able to collect a tiny fraction of these antiquities. The majority of it is getting smuggled out of the country and even being sold or auctioned openly for foreign collectors. Three international “art” websites are openly selling toys, pottery, jewellery and so on from Indus Valley Civilisation, including some from Rakhigarhi, at prices that range from $75 to $3,000.

Bhattacharya tells The Telegraph, “It’s a pity we don’t have a dedicated ministry of antiquities.”