Sarmistha Dutta Gupta has been researching the massacre of Jallianwala Bagh for a while. When she had amassed a range of material on the 1919 genocide of unarmed Indians — estimates of casualties are 300 upwards — by British troops in Amritsar, the independent researcher-writer-curator decided to do a public history project in the form of an installation exhibition.

Titled “Ways of Remembering Jallianwala Bagh and Rabindranath Tagore’s Response to the Massacre”, the exhibition opened at Calcutta’s Victoria Memorial Hall in March 2020. The irony, of course, was stark; a Raj memorial playing host to an exhibition commemorating a massacre perpetrated by the Raj.

When the exhibition was called off abruptly because of the pandemic and the lockdown that followed, Dutta Gupta started writing about her process of research and curation. These writings took the shape of the Bengali book, Jallianwala Bagher Journal, which was released in August this year.

Dutta Gupta begins her journal with an interview of the historian Vishwanath Dutta in his south Delhi apartment. Dutta was born in a house that was a stone’s throw from Jallianwala Bagh. He is also the author of Jallianwala Bagh, a 1969 publication and the book New Light on Punjab Disturbances published in 1975.

Dutta Gupta met the 93-year-old historian a year before he died in December 2020. In her journal, she writes about the experience. When Dutta Gupta asked the elder when he had heard about the tragedy for the first time, he broke down.

Turns out he was born seven years after the massacre, and had lost his mother when he was only a year old. He regularly walked the grounds of Jallianwala Bagh in his childhood and teenage years. Dutta replied: “I heard about it when I was only four. My sister narrated how my mother had beat her breast and wept inconsolably when she heard that shots had been fired. She feared my father who had been out that day must have been shot.”

Many more such personal experiences constitute Dutta Gupta’s journal.

Dutta’s father, Brahmananda Dutta, who wrote poetry in Urdu and Farsi and ran a business in Amritsar, had not been at the fateful gathering that day in 1919. But many people he knew were there. His friend Ratanchand Kapur was one. According to Dutta's daughter, Nonica, who is also a historian, Kapur escaped with a bullet injury in his foot.

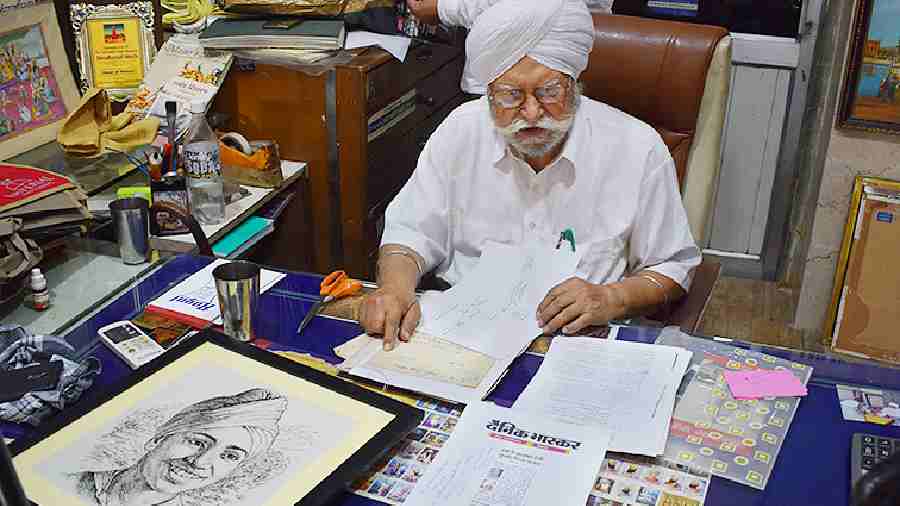

Jagdish Singh remembers his father who survived the massacre. Courtesy, Sarmistha Dutta Gupta

In another entry, Dutta Gupta writes about yet another interview. The 80-something Surinder Singh owned an art heritage shop in Amritsar. His paternal uncle had died in the Jallianwala Bagh firing. Singh’s grandfather Gyan Singh was a nakkas artist who decorated nikkahnamas or marriage contracts.

On the fateful day, Gyan Singh had gone to the Jallianwala Bagh meeting with his eldest son Sunder. Two bullets hit Sunder — one in the head and the other in the chest. Gyan tried to escape with his injured son but couldn’t. Two days later, when the government allowed the family to cremate Sunder, they did not have the means and none of their relatives helped out of fear. Surinder Singh had shown Dutta Gupta a black and white sketch of a smiling teenaged Sunder, a sketch done by his father Gyan Singh.

Dutta Gupta tried to learn as much as she could about the Jallianwala widows too.

She travelled to Amritsar’s Sultanwind area where Congress worker Bhagmal Bhatia’s son’s house stands. Bhatia could not escape the firing at Jallianwala that day. But his widow Attar Kaur lived in their Sultanwind house the rest of her life. There is a road named after her that the researcher saw for herself.

Dutta Gupta, who had been on a personal visit to Jallianwala Bagh in 2016, says that thereafter she could not get out of her head the stream of festive crowd moving in and out of Jallianwala Bagh. She says, “I kept wondering about the trajectory of the site… Visitors were just streaming past the bullet marks and gallery exhibits without being engaged in any way with the larger significance of what is on display.” On her return from Amritsar, she started reading up on Jallianwala and in the process, she says, she realised how it has been “decontextualised” in history textbooks and popular films.

“The installation exhibition was curated to question our forgetfulness around many significant facets of this outrageous episode in our history,” she says.

Post the massacre, Rabindranath Tagore had given up the knighthood awarded to him in 1915. Says Dutta Gupta, “Almost everybody is aware of this, but not the fact that he also wrote to the Viceroy against the violently racial martial law regime in Punjab and the monstrous effects of World War I on the geography.”

What is also largely forgotten is that Tagore was not in favour of the idea of raising a memorial at Jallianwala Bagh. The memorial was proposed by the Indian National Congress in 1920 and built in the newly independent India in 1961. Says Dutta Gupta: "Tagore's disagreement with the idea of monumentalising memory is something that inspired me and Sanchayan Ghosh, my collaborator."

She adds, “When the proposal of the memorial was mooted in 1920, many people from all over the country had felt an immediate need to externalise their memories and their sense of shock and grief into some kind of a physical object or a structure. But over time, especially in the last 50 years, the brick-and-mortar monument has ceased to be a memorial of loving compassion for those who lost their lives. It is today disconnected from stories of individuals and communities.”

The exhibition and the journal is possibly Dutta Gupta’s way of recreating the context of a memory that has come loose.