No, this story is not about Madam Politron. I don’t even have a photograph of her to share with you. In fact, her story — the little I know of it — is the downstream to the upstream that is this narrative. But as I see it, she makes the far near enough. Perhaps she will do that for you too.

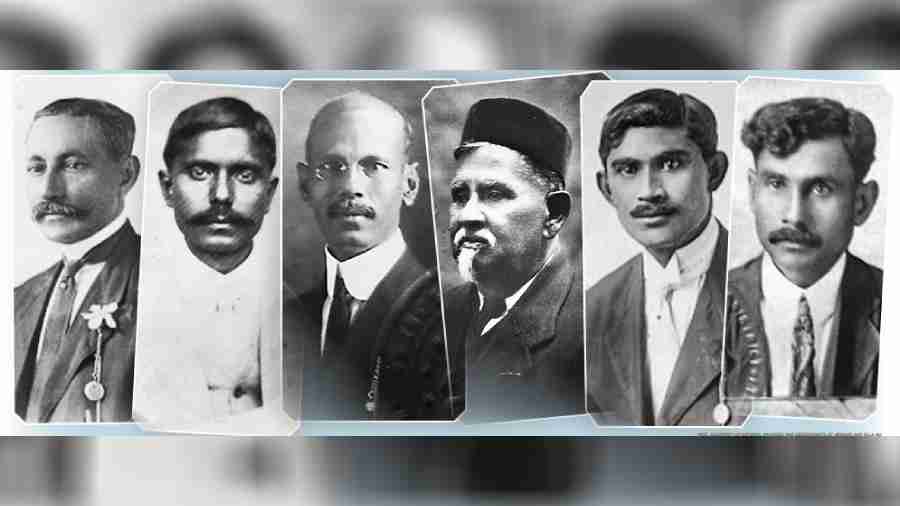

One June day in 1897, the SS St. Louis sailed into New York Harbour. “Twelve Muslim men from Calcutta and Hooghly were on board the steamship,” writes Vivek Bald in Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of South Asian America. The excerpt goes thus: “The Bengali men on board the St. Louis were peddlers, on their way to the beach resorts of New Jersey — Atlantic City, Asbury Park, and Long Branch. In their home villages, their wives, mothers, sisters, and daughters produced finely embroidered silk and cotton fabrics — handkerchiefs, bedspreads, pillow covers, and tablecloths — in a style known as chikan; no doubt, the luggage that each man carried was filled with such goods...”

Niyamul Haque was either on that ship or another one like it around the same time.

Niyamul and his family — wife and children and the entire extended clan — lived in Babnan’s Haldarpara. Babnan, not to be confused with Bagnan, is in Bengal’s Hooghly district.

The Portuguese’s Golin, Dutchman Van Brouche’s Oegli and Ain-i-Akbari’s Hughli was wrested by the Mughals from the Portuguese sometime in the early 17th century.

In Hooghly Zillar Itihash O Bangasamaj, Sudhirkumar Mitra writes about all the things Hooghly was famous for. Bainchi, Khamarpara, Maahesh for pital utensils; Janai and Baksa for mishtannashilpa; Mayapur, Chanditola, Narayanpur and almost all other places for wickerwork and chikankari.

Sheila Paine, an expert in textiles and a travel writer, describes chikankari as “floral embroidery on white fabric” developed during the Mughal period in Calcutta, Dacca and Lucknow.

According to Mitra, chikankari was a craft Muslim women of the area were adept at. And in a 1917 edition of The Hindusthanee Student, which was the “official monthly organ of the Hindusthan Association of America”, one N.C. Das writes, “Their men used to sell these products in home-markets until about a century ago before the decline set in. Not discouraged, however, they ventured out to distant lands…” But a footnote in Bald’s exhaustive research cites ship records listing some of the men making their way to the US to peddle chikan goods as “embroiderers”.

Niyamul, however, did not make it into the US the first time. One of his grand-nephews, Kausar Hossain Mondal, who is also from Babnan but currently working in Mongolia, says over Facebook Messenger, “He was deported, but he went back.”

Mind you, all of this was happening almost a quarter century before the US passed a strict anti-Asian immigration law in 1917. It was also very different from the white-collar immigration of the 1960s, post the easing of the immigration laws.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Comparative Media Studies And Writing web page describes Bald as a “scholar, writer, and documentary filmmaker whose work focuses on histories of migration and diaspora, particularly from the South Asian subcontinent”. What does not find place in the professional bio is that Bald’s mother was born in pre-Partition India and left for the US in the 1960s for a PhD in politics at Harvard.

Bald’s identity as a South Asian-American played a part in him arriving at and then piecing together the story of Bengali Harlem.

Bald tells The Telegraph how in the 1990s he was part of a larger circle of second-generation South Asian-American artistes and activists. It was within that circle that he met and became friends with Alaudin Ullah, a stand-up comedian. From him, Bald learnt about the curious history of his father Habib Ullah.

Habib Ullah had arrived in the US from what is now Bangladesh in the 1920s, married a Puerto Rican woman and moved to Harlem. Bald says, “It just went against the grain of what I knew of South Asian-American history which until that point had focused primarily on Punjabi migration to the West Coast.”

Harlem is a neighbourhood in New York City’s Manhattan borough. During the end of the 19th century, its demographic was changing from poor Jewish and Italian to black and Puerto Rican people. And by the 1920s, it came to have a largely African-American community.

Digging his way through the New York municipal archives, Bald discovered there were others like Habib Ullah, men from East Bengal who had been ship workers but eventually jumped ship and settled down in Harlem.

But then he came upon records of two Harlem brothers, Bahadour Ali and Rustam Ali, who, unlike these ship workers, had actually been born in the US — in Mississippi and Louisiana — around the turn of the 20th century. Their father was listed as Moksad Ali and their mother Ella Blackman.

I must make clear at this point that the ship workers and peddlers represent two different migratory patterns. Moksad was a peddler, Habib Ullah was not. What was common, apart from the time of arrival in the US, was their Bengali roots and their Bengali shoots in Harlem.

Moksad would have first landed in the US around the same time as Niyamul. Bald describes the immigration procedure that awaited them — “they were poked and prodded like cattle, their hair combed through for lice, their eyelids pulled back with a metal hook to check for trachoma”

Going through census records and ship passenger records, a pattern became apparent to Bald. He says, “The peddlers would come at the beginning of summer every year with their chikan goods. A certain number of them in this network settled down in the US, in New Orleans and Atlantic City, and others circulated between India and the US.”

Remember, the departure of these men from their native places coincided with the period when British manufacturing was gaining muscle in India. Also note that these men were not coerced, were not indentured labourers nor were they driven away, at least not to our knowledge. Somebody must have told somebody who whispered it to somebody that there was a better life awaiting shaat shomuddur paar and they set sail with Ulyssean zeal.

There was a widespread craze for Oriental goods in the US those days. New York’s wealthy would decorate their smoking rooms with rugs from India, and hookahs and such. The working classes also wanted a piece of the Orient, something to match their pockets — a scarf or a wall hanging or even an embroidered handkerchief.

As the network developed, these goods were shipped to other port cities such as New Orleans, Savannah and Charleston. Older peddlers who had settled here received shipments and distributed them to younger peddlers — brothers, sons and nephews — who had arrived separately.

Bald tells me that many of the shipments from Bengal could be traced to a street in central Calcutta. Today, Collin Lane, which is a little walk down Mirza Ghalib Street, is full of tailoring shops and Bangladeshi restaurants. There is no trace of chikan or chikondars, and no one on the street seems to be familiar with one of its old names — chikanpara.

Back to our enterprising peddlers. On May 25, 1900, the Daily Herald of Biloxi, Mississippi, published a dispatch from a New Orleans correspondent about a group of “Hindoo peddlers” there. The tone of the report — about one “bronzed gentleman” with a “scraggy beard” “humped over” his bicycle like a camel — was condescending.

The dispatch read: “There was something monstrously incongruous in the idea of a Hindoo on a bike… and I stood transfixed with amazement, while he very nearly ran me down. But instead of saying, ‘Make way, oh! Sahib, for thy servant to pass,’ as he should have done, he called me an old fool in very good English, and asked me whether I wanted to be killed.”

In other words, colour of the skin notwithstanding, the outsider was no was good as an insider.

Moksad Ali married Ella Blackman in 1895, Abdul Hamid married Adele Fortineau and Sofur Ally married America Santa Cruz in 1900, Joseph Abdin married Viola Lewis in 1906. These women were either Creoles or African-Americans from New Orleans.

Like them, Madam Politron was also a woman of colour from one of the port cities. “She was a businesswoman,” says Mondal. He does not know the details of how she met Niyamul, and when and why the much-married Niyamul decided to marry her and return to Hooghly. What he does know though, from legacy family stories, is that in time Madam Politron embraced Islam, learnt Bengali and the little and big ways of the land, had a son and a daughter with Niyamul, even learnt to cook laushak. She died in Babnan, where her grave still stands.

This story, however, is not about Madam Politron; it is about Niyamul and Moksad and those 12 men aboard the SS St. Louis and their ilk. But then you would have worked that out by now.