Cut to rural Anand in Gujarat right after Independence. A time of five-year plans being rolled out and nation-building. Manthan, Shyam Benegal’s cinematic telling of the success story of the state’s dairy farmers, which eventually led to the White Revolution, is like a silver slice of history.

Manthan or The Churning from 1976 is once again in the news. The film’s original prints were “restored from ruin” by the Film Heritage Foundation, re-released at the Cannes Film Festival this year and screened at 100 theatres across India.

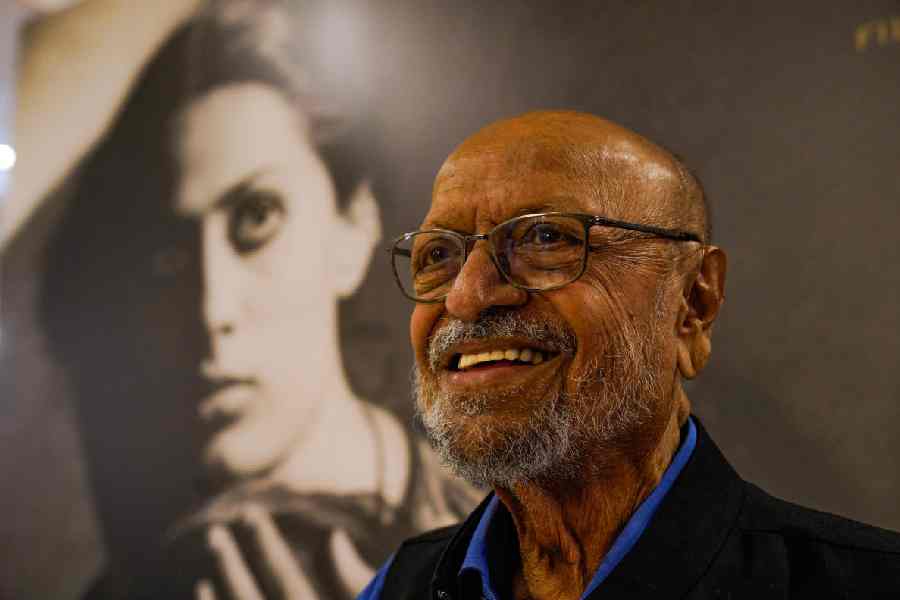

Speaking to The Telegraph over the phone from Mumbai, director Shyam Benegal, who is now 89, sounds excited. He launches into a recollection of the times. However, most of what he offers is not to do with his film but how the farmers benefitted from the movement and the entrepreneurship of two men towards that goal.

“We went from being a milk-deficient nation to being the largest producer of milk, earning valuable foreign exchange and also raising the living standards of the dairy farmers. It was a win-win situation,” he says. You would think it is a personal success, such is his effervescence.

Gujarat has always been a milk-rich region. However, business was rife with the exploitation of dairy farmers by traders and agents. “Individual farmers were being cheated left, right and centre, as middlemen tend to take the lion’s share of everything,” Benegal continues. The idea of Amul — short for Anand Milk Union Limited — was born as a solution to this unfair practice. It was a cooperative founded by Tribhuvandas Kishibhai Patel, a cousin of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel.

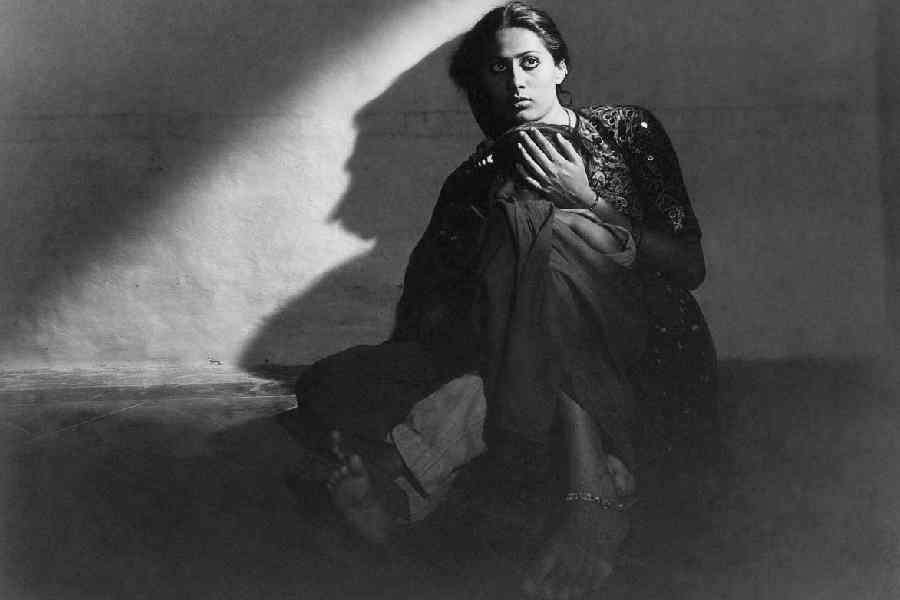

Manthan by Shyam Benegal.

Benegal speaks of the events like it was yesterday. “Sardar Patel said, the farmers produce so much milk and yet they aren’t getting the benefit. And that is how Tribhuvandas came to organise the Amul dairy under the Gujarat Milk Marketing Federation.”

And, of course, there was Verghese Kurien, “the magician behind it”.

Kurien had a degree in mechanical engineering from Michigan State University in the US. “When Tribhuvandas heard about him, he invited him to help with the factory and equipment.” Kurien subsequently trained in dairy engineering from Australia to make Amul the growth story that it became.

“Once it started showing results and the farmers were convinced they were getting their product’s worth, two things happened,” says Benegal. “First, the quality of the milk improved greatly, as the farmers got their due without having to adulterate the milk. And second, there was surplus; so they decided to make milk products like cheese, butter and baby food, which was till then being imported.”

However, there was a problem. After the initial phase, Kurien was reluctant to stay on in Anand. He had a job waiting for him in Bombay. But Tribhuvandas offered to pay him twice the amount and also promised to build him a house with all the modern amenities he was used to. By this time, Kheda, Anand and other centres had begun to grow. “The economics of milk changed the nature of the entire region,” says Benegal.

But how did all this translate into a film?

“When Amul started to make new products, they also needed advertising,” Benegal continues with his narrative. “Kurien, however, did not want to go to Lintas. He was keen on working with an agency that was more familiar with the grassroots. That is how he approached Advertising, Sales and Promotion (ASP).” Benegal, who was earlier employed with Lintas and had begun to make documentary films, joined ASP soon after and began to handle the Amul account.

Another thing happened around this time. “In those days, Polson was the established name in milk and milk products. They could charge whatever they wanted because there was no competition. When Amul came, they got wiped out.”

Clearly, the context of Manthan is of much greater importance than the film itself.

“Remember, in all of this, the interest of the farmers was maintained as primary,” says Benegal. He talks about how the standard of living in places like Anand and other towns went up. Even in the villages, it was common to see a car or a tractor in front of a house. “The happy story caught the eye of the Government of India. There were people like Nehru who immediately saw a lot of value in all this. And Kurien was asked to replicate it in other parts of India. It was an exceptional success story of the first and second five-year plans,” he adds.

And again the itinerant question — how did all of this translate into a film?

It was Kurien who came up with the idea of a film. Benegal, who drew up the costing for it, asked, “You are a cooperative, how will you afford it?” Kurien replied, “The farmers will produce it.” And that is how the world’s first crowdsourced film materialised, with every dairy farmer chipping in ₹2. The title sequence of Manthan reads “500,000 farmers of Gujarat present...”

An animated Benegal says, “I asked Kurien, who would want to see this film. And he said, ‘I will ensure it is seen by the farmers’.” As he tells it, within a few weeks of release, the film not only recovered the money but also made enough to produce three or four documentaries. “It was all very unreal,” he adds.

Finally, the maestro starts to talk about his film.

“We shot in Sanganva village in Saurashtra. I needed that kind of a remote landscape, because by the time the film started rolling, Anand and such locations had moved on, their very nature had changed.”

Benegal recalls the dedication of his cast. “Everybody got into the spirit of the film. Nobody complained that we shot in a remote village with no facilities. Everyone had to take a little lota and go into the fields to do their big business. They all lived in a large house, which was the village headman’s house, sleeping on the floor, sharing space like students on excursions.”

The stories pour out. How Naseeruddin Shah, who played Bhola, a lower-caste community leader, was very particular that everything should look authentic. He wore the same costume for one-and-a-half months, without washing it. Adds Benegal, “Smita too wasn’t functioning as an actress doing a role, she became a part of the house that you saw. All this made a huge difference, in terms of the actors’ body language, etc. You could say it was method acting to the nth degree.”

Those were courageous times indeed. The climate, the filmmakers and actors, the works. Makes one wonder — perhaps it is time for another story about the farming community. Any makers?