Change often the white shirts, dress smartly, play board games or chess but not those games which are not useful on account of the breath which goes from one player to the other.

Those to-dos were pronounced by an Italian physician in the 14th century in the context of The Black Death or plague that swept through Europe and Asia. Souvik Mukherjee began his talk titled “In and Out of the Magic Circle” with this quote from American historian Giuseppe Mazzotta’s 1986 book, The World at Play in Boccaccio’s Decameron.

Decameron by Giovanni Boccaccio is about a bunch of Florentines isolating in a villa to escape The Black Death. Mazzotta writes: “Caught in this predicament, the young people of the lieta brigata, who had met by chance in the church, play and tell stories in simulated obliviousness of the surrounding chaos. And as they play chess or checkers and dice to pass the time, there is the flicker of a dark premonition that they themselves may be pawns in the Game of Death, or its shadow, the agon of Time.” Mukherjee’s talk, organised by the Indian Museum and hosted on YouTube in keeping with the limitations of the lockdown, revolved around the twin ideas of pandemic and play.

A Persian chess set iStock

The assistant professor and head of the department of English at Presidency University peppered his talk with the occasional peep into his personal collection of board games that he picked up from around the globe. If Mukherjee turned focus on the Matryoshka chess set at some point, at another time he drew attention to the Viking chessboard.

Mukherjee also brought up the theory by Dutch historian Johan Huizinga. According to Huizinga, play is an important aspect of human culture and it happens within an imaginary space or magic circle where things that are not accepted in real life are kosher. Says Mukherjee, “Yet what you do in play has an impact on real life and how you play is very much influenced by real life.”

Nonetheless, one is reminded that it is not always about the game mirroring real life. The game is also the great escape. Mukherjee brings up a Burmese chess set, in which every piece resembles the Burmese elephant, and one other very ornate set from Nepal. He adds, “When playing with these, they become a story.”

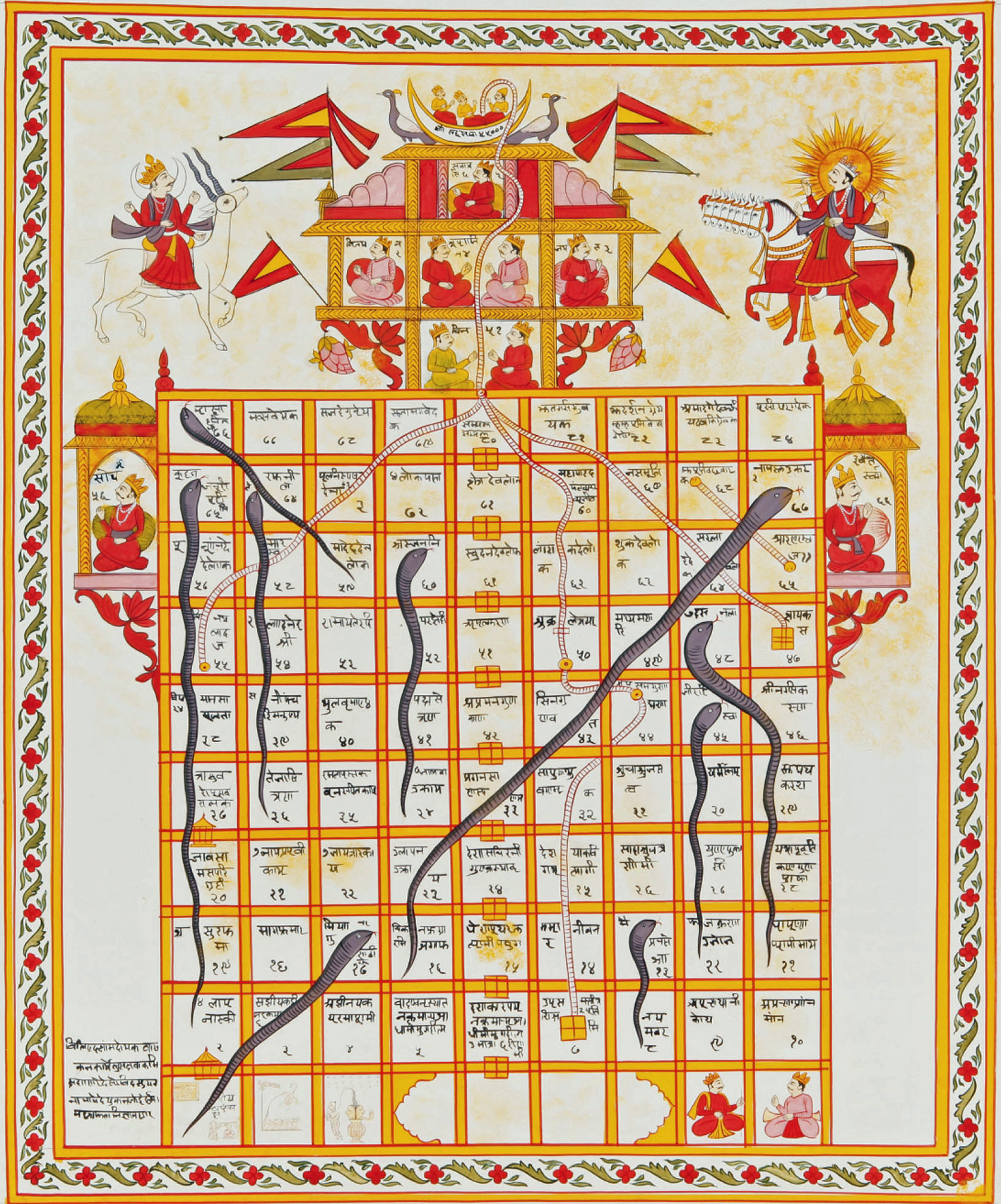

Mukherjee also invokes India’s rich tradition when it comes to board games. He lists the following: gyan chaupar, jnan bazi, moksha patam. All these are versions of the snakes-and-ladders game. He says, “The serpent is a way of life in gyan chaupar. Going through ups and downs is part of karmic life... But in the Christian paradigm there is no rebirth. The snake or serpent is an evil creature in the Biblical world.” He talks about a Jain version of the gyan chaupar in the National Museum of Delhi and it seems a Sufi version of the board game is housed in the Ashmolean Museum in the University of Oxford, UK.

The talk is no idle listing. It is a mix of personal, collective and cinematic memory. Mukherjee invokes Satyajit Ray’s Shatranj Ke Khilari to illustrate how the game mirrors life. He points out that in the game as we knew it in the India of the 19th century, among the pieces there was a raja and a mantri. But as Lord Dalhousie’s army approaches Oudh, at the board, quite symbolically, Mir sahib calls out “check-mate” as he slides the malika, or queen, into position.

Mukherjee refers to chaturanga, which is said to be the oldest game of chess and is supposed to have originated in India. He goes on to talk about how people in south India are manufacturing board games and there is a new industry revolving around them.

A national conference on ancient and medieval Indian board games was held in Mumbai last year. Aman Gopal Sureka, a Calcutta-based IT consultant and a board game enthusiast, was also present. He is keen not just on reviving the ancient board games of India but is also currently developing mobile applications based on ancient board games through his company, Khol Khel.

He says, “Chaupar was played quite prolifically in ancient times and there used to be a competition in the Calcutta Marwari community.” It was played by both men and women. While the women played with cowries, the men played with square sticks. Though they used the same board, the games were totally different. The one with cowries was a game of chance and the other a game of strategy, says Sureka, whose Buddhi Yoga is a mobile app that recreates snakes and ladders. But that is another story.

Mukherjee takes note of card games too. He talks about the standard 52-card deck and how it is possibly a European import. He tells the story of the ganjifa cards from Bishnupur and Odisha, how they originated in Iran and are referred to in Abul Fazl’s writings and the Baburnama.

Mukherjee wraps up his talk with senet, a board game from ancient Egypt, and the Royal Game of Ur from Mesopotamia. Both were played by the pharaohs. He adds, “They were played not just as games but also to decide on their regular activities.”

That’s the other thing common to pandemic and play. Both made commoners of kings.