The flap of a seagull’s wings can alter the course of weather forever. And that a UK PM candidate of Indian origin would one day worship a Hereford or Holstein bovine in London to gain political mileage, however hysterical, was going to happen from the moment the first lascars were herded onto British steamships docked in Indian ports way back in the 18th century.

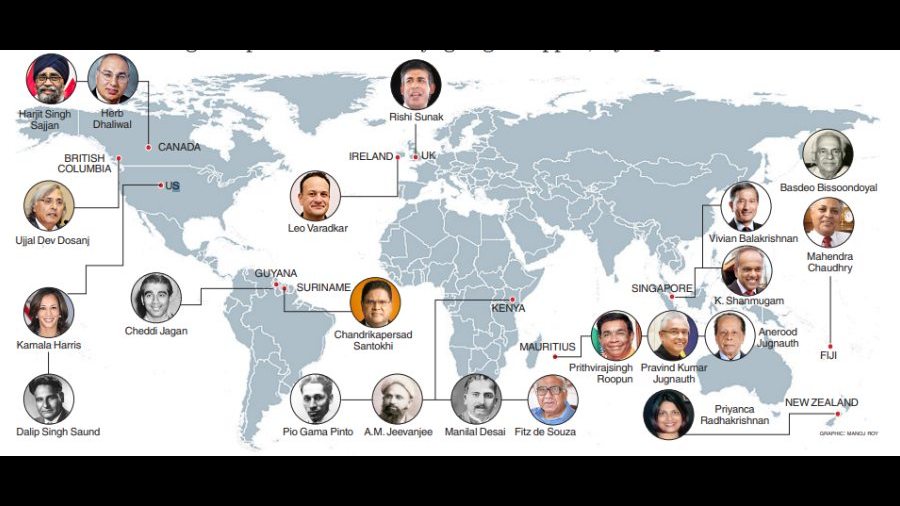

That two centuries later, there would be a Priyanca Radhakrishnan of Kerala connect as minister in Jacinda Arden’s cabinet in New Zealand; that a Pravind Jugnauth with roots in Ballia/UP would be Prime Minister of Mauritius; and that Vivian Balakrishnan and K. Shanmugam would be ministers in Singapore’s Lee Hsien Loong government is anything but chance.

Everything was leading up to each of these milestones, for years now. Like when in the early 19th century, waves of Indian indentured labourers sailed out from famine-ravaged geographies to Mauritius, Reunion, Guyana, Trinidad, Jamaica, Surinam, Fiji, Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, South Africa… Slavery had been abolished in the British and European colonies and these not-slaves were to fill the need gap. Still later that century, south Indians migrated to Southeast Asia — Ceylon, Burma, Malaya.

What a great centrifugal force imperialism was! How the subcontinent churned and what a great scattering resulted!

Many of the abandoned lascars stayed on in London, Liverpool, Cardiff and Glasgow. Rishi Sunak may not have any friends from the working class, but in Kenya, where his family settled down after they left Punjab, Indians worked hard to build the Kenya-Uganda railway line. A good many of them died during this time, mostly of heat and disease, while nearly a hundred wound up in the stomachs of man-eating lions. Of those who stayed on and their progeny, most upped and left for the UK in the 1960s after Kenya became a Republic.

The great-grandparents of the current President of Guyana, Mohamed Irfaan Ali, had left India for the sugar plantations of British Guiana, a British colony in South America. The paternal grandfather of Portugal’s Prime Minister Antonio Costa is from Goa. Then there is President Prithvirajsing Roopun of Mauritius — you might have seen photographs of him offering puja at the Mahabodhi temple in Bodhgaya — and President of the Republic of Suriname Chandrikapersad Santoshi, who is in news right now because of Lok Sabha speaker Om Birla’s visit to Paramaribo last week.

Early 20th century saw the “other kind of migration”. Traders, students and single men moved from India to Canada, Australia and South Africa. And you could say that history started to leaven time for Kamala Harris and the Samosa Caucus way back in the 1900s, when the first Punjabis arrived in California and the Pacific Northwest.

In “Colour and Citizenship”, a report on British race relations from 1969, Joseph Rose quotes a Sikh immigrant in London as saying: “We had started feeling British but then there were so few Indians but now there are so many of us, that we have started feeling Indian again.” Today, with 32 million people of Indian origin all over the world, it should be a matter of little surprise that not just Sunak-in-waiting, but worldwide there are five Indian origin heads of government, three deputy heads of government, 56 cabinet ministers, and four additional ministers, according to the 2021 Indiaspora Government Leaders’ List.

After Dalip Singh Saund graduated from Panjab University, he left for the US to study food canning. That was 1920. His plan was to return and set up business, but that never happened. Saund lobbied for Congress to pass a bill that would allow Indian immigrants to become naturalised citizens. In 1949, he became an American citizen and in 1957, he became the “first Asian, first Indian American, first Sikh and first follower of a non-Abrahamic faith” to be elected to the Congress.

Around when Saund was setting foot in the Congress building in Washington D.C., in British Guiana, Cheddi Jagan of the People’s Progressive Party was already a big name. In 1953, he had won elections to become chief minister and though Winston Churchill with ample help from John F. Kennedy branded him a Communist and tripped his government, his political run continued. In a speech in the US, he said: “I am, I believe, generally dismissed in this country as a Communist. That word has a variety of meanings according to the personal views of the man who makes the charge… I wish to see my country prosperous and developing, its people happy, wellfed, well-housed, and with jobs to do… in this I am a socialist.” Jagan became the president of independent Guyana in 1992.

Around the early 1900s, the Indians in Kenya, who had been there for some years, started to demand elective representation. The European settlers opposed this. These circumstances saw many Indians take to politics. A.M. Jeevanjee, a Muslim businessman along with some others went on to form the East African Indian National Congress in 1914. Other Indians in Kenyan politics from the time were Manilal Desai, Pio Gama Pinto founded the political party called Kenya African National Union in 1960, and there was Fitz de Souza who campaigned for the independence of Kenya.

In 1994, when Nelson Mandela formed the government in South Africa, there were seven cabinet ministers of Indian origin. And in Canada, long before Harjit Singh Sajjan became minister in the Justin Trudeau government, there was Herb Dhaliwal (Harbance), the first Indian Canadian to become a federal minister in 1997. Ujjal Dev Dosanj became the 33rd premier of British Columbia in 2000.

As times changed and context, their core politics and -isms changed. Not all of it was determined by their brownness.

Basdeo Bissoondoyal had been involved with the Arya Samaj and inspired by Gandhi. He launched the Jan Andolan Movement to educate the Indo-Fijians. After the 1982 polls, when he was offered the post of the first president of the Republic of Mauritius, he refused. Anerood Jugnauth, however, was prime minister for four consecutive terms and President from 2003 to 2012. When he did step down, it was to hand over the reins to his son.

Mahendra Chaudhry was the fourth PM of Fiji. When he was overthrown in a coup, Haryana chief minister Om Prakash Chautala asked the Indian government to intervene. Chaudhry’s grandfather had been from Rohtak after all. Chaudhry never got the support of ethnic Fijians, and neither Dhaliwal nor Dosanjh supported the cause of the indigenous people of Canada.

So there is brown and there is brown. And, brown for many of these politicians today is just a shade to powder over their actual convictions come election time. Remember Kamala Harris on the Mindy Kaling show bonding over masala dosa just before the US presidential elections? Sunak’s temple visits are of the same genre.

On September 5, the ruling Conservative party of Britain will have a new leader; the name of the next incumbent of 10 Downing Street is unlikely to be Rishi Sunak. But no matter what the outcome, history is flapping its wings and nothing will be quite as before.