Let’s begin with a riddle. Which is the first messbari of Calcutta? No? Try the second one then. Here are clues aplenty — it is over two centuries old, located in the heart of the city, has a 128-feet-long verandah, has had many makeovers in the past two centuries. Still thinking? We will come back to it later. First, a walk through some of the vintage messbaris.

Messbari is an urban Bengali coinage. It is born off the mess, the name for the area where military personnel socialise, eat and live together. (Bari in Bengali means home.)

We begin our tour with the dilapidated three-storey house on 134, Muktaram Babu Street in central Calcutta. Its claim to fame — renowned Bengali author Shibram Chakraborty spent the better part of his life in a small room on the first floor. Early morning or late night is a good time to stop by, if you want to get that unmistakable mess flavour.

The house had offered an austere life to the legendary humorist, who belonged to the royal family of Chanchal in Malda. Shibram wrote, “Muktaram-e theke taktarame shuye suktaram kheye ami Shibram.” The humour loses its edge in translation, nevertheless, this is what it means — “I stay at Muktaram (Street), my bed is a taktaram (a wooden plank), I survive on suktaram (a reference to sukto, the bitter gourd starter typical of a Bengali meal) and my name is Shibram.”

We know we are at the right address, but we cannot spot an entrance. There is a narrow alley adjacent to the building; we plunge in without hesitation. Sure enough, a middle-aged man in a vest and towel answers to our hollers. Tapan Maity is the caretaker-cum-cook-cum-security-cum-bellboy-cum-manager of this establishment. He claims to have cooked sukto for Shibram.

Maity reluctantly agrees to show us the fabled room now inhabited by other boarders. We can hear him mumbling that we are not to touch any of the belongings lying around but by then we have spied the wall with the numbers. Shibram never allowed anyone to paint the walls of his room. He would scribble his contacts on them. Why? Because notebooks tend to lose themselves, not walls.

This mess also housed at different points of time Bogra Congress leader Satish Chandra Sarkar, dhrupad singer Bhootnath Bandopadhyay, footballer Surjya Chakraborty, essayist Upendranath Bhattacharya and freedom fighter Taranath Roy. Among those who visited Shibram here were revolutionary poet Nazrul Islam, newspaper editor Tusharkanti Ghosh, and filmmakers Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak.

By the mid-19th century messbaris started mushrooming across the north and central parts of Calcutta. In his memoirs, writer Upendranath Ganguly has touched upon his nephew, writer Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay’s short stay in a Bowbazar mess. Many believe that this stay inspired him to write the novel, Charitraheen, in which the protagonist is a mess boarder who falls in love with a domestic help.

Amritalal Basu’s satire Chatujye-Bnarujye, Rajshekhar Basu’s short story Birinchibaba, Sadhan Sarkar’s Jai Maa Kali Boarding, Tarashankar Bandopadhyay’s Holi and Narayan Gangopadhyay’s novel Ektala are some of the best literary specimens centred on the mess culture of Calcutta.

Writer Saradindu Bandopadhyay’s fictional creation, detective Byomkesh Bakshi, also started out from a mess on Harrison Road, now Mahatma Gandhi Road. Saradindu himself used to stay in the attic (the Bengali word for it is chilekotha) of a mess at 66, Harrison Road.

A 10-minute drive from Shibram’s erstwhile abode brings us to Saradindu’s mess. Climbing the shadowy stairs and following in the footsteps of Saradindu would have been the best way to commune with the cases of Byomkesh. But we are not allowed. “No visitors to the rooftop,” says the caretaker. He cannot be bothered with explanations, besides he is busy running his canteen. We can smell out that day’s brunch menu — machh, bhaat, dal and sabji.

There is a confusion about which one of the two rooftop rooms belonged to Saradindu. “They must have made some heretical changes in the name of restoration, and that’s why they don’t want us to take a look,” says Das who has come along.

Poet Jibananda Das too spent a few years on the first floor of this very building. Several Bengali films and plays of the 1950s and 1960s have also been woven around the mess culture — Sare Chuattar, Saptapadi, Basanta Bilap and many more. Popular comedian Jahar Roy himself used to stay in a mess in Patuatola Lane of College Square.

Messes played a crucial role in Bengal’s freedom movement as well. Das says how many of these were a safe haven for freedom fighters. Consequently, police raids on messes became a routine affair. British police commissioner Charles Tegart once raided Shibram’s mess. The cops also made surprise visits to messes on Waliullah Lane, Cornwallis Street, Metiabruz, Nilmani Dutta Lane and Gopimohan Dutta Lane. Revolutionaries Khudiram Bose and Prafulla Chaki were trained at the mess on 32 Gopimohan Dutta Lane for the attack on Muzzaffarpur district magistrate Kingsford.

And that brings us back to the riddle. So which is Calcutta’s first mess?

In the spot on Dalhousie Square, where now stands the GPO, used to be the city’s first mess — the residential quarters of British writers or sub-junior officers. When that building was flattened in the cyclone of 1737, a new mess came up. The Writers’ Buildings is the second messbari of Calcutta. And now with its non-ending restoration work, the Bengal Secratariat is, well, still a mess.

Evening adda at messbari-turned-Ruby Boarding, College Street Subhendu Chaki

Saradindu Bandopadhyay’s chilekotha at 66, Harrison Road Subhendu Chaki

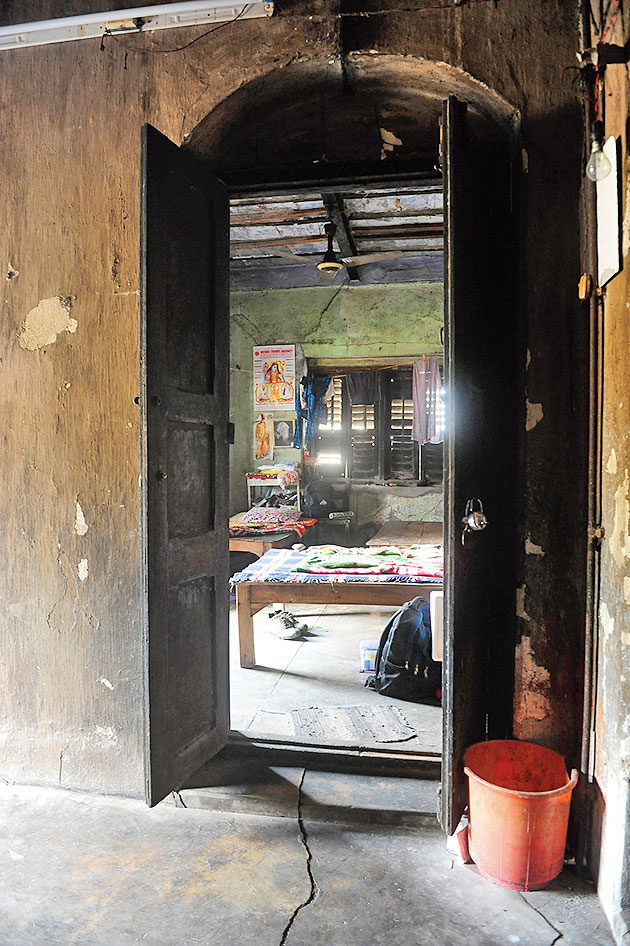

Kitchen at the 134 Muktaram Babu Street messbari Subhendu Chaki

Author and columnist Jayanta Das, who has done extensive research on messes, says that the messbari culture is an early 19th century phenomenon. At the turn of the century, as the importance of education became apparent, the city with its possibilities of higher studies started to attract educated men from interior Bengal. Many also moved to the city for better employment opportunities. These migrant men would rent a room in a messbari or a slice of it, depending on availability and affordability. Those among them who were looking for employment used to cook for the others in exchange for lodging. Social reformer Ramtanu Lahiri, who had come to Calcutta from Krishnagar in 1826 at the age of 12, was one such person.

While Lahiri lived in a mess at Hatibagan in north Calcutta, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, educationist, social reformer, Renaissance man, stayed in another — the house of one Bhagabat Singha in central Calcutta’s Burrabazar area. This was in 1828.

Das keeps spewing history relentlessly. Founder of the Sadharan Brahmo Samaj, Sivanath Shastri, had arrived in Calcutta from Majilpur village with his father at the age of nine. The house they moved into belonged to Shastri’s maternal uncle, Dwarkanath Vidyabhushan. This house was later turned into a mess. This is where Shastri first met Vidyasagar. In fact, acting on Vidyasagar’s proposal, Dwarkanath published the weekly newspaper, Somprakash, from this very building. Years later, Shibram too started publishing Jugantar from his mess address.

Shibram Chakraborty’s room at 134 Muktaram Babu Street, the walls of which still bear his scribblings Subhendu Chaki