Even as India geared up for the pran pratishtha at the newly-built Ram temple in Ayodhya with the Prime Minister leading the way, Anand Patwardhan’s 1992 movie Ram Ke Naam was scheduled to be screened in various places across the country.

Ram Ke Naam was released ahead of the demolition of Babri Masjid in December 1992. In Hyderabad, students of Nalsar, the law school, fought and screened it. Telangana is a Congress-ruled state, but at Marley’s Joint Bistro in the Sainikpuri area, also of Hyderabad, Right-wingers disrupted the screening, following which police arrested four of the organisers. At the Film and Television Institute of India in Pune, reportedly 25 people entered the campus chanting “Jai Shri Ram” and hurling abuses at the students. In Ashoka University in Sonipat, students were forced to take down posters of the film.

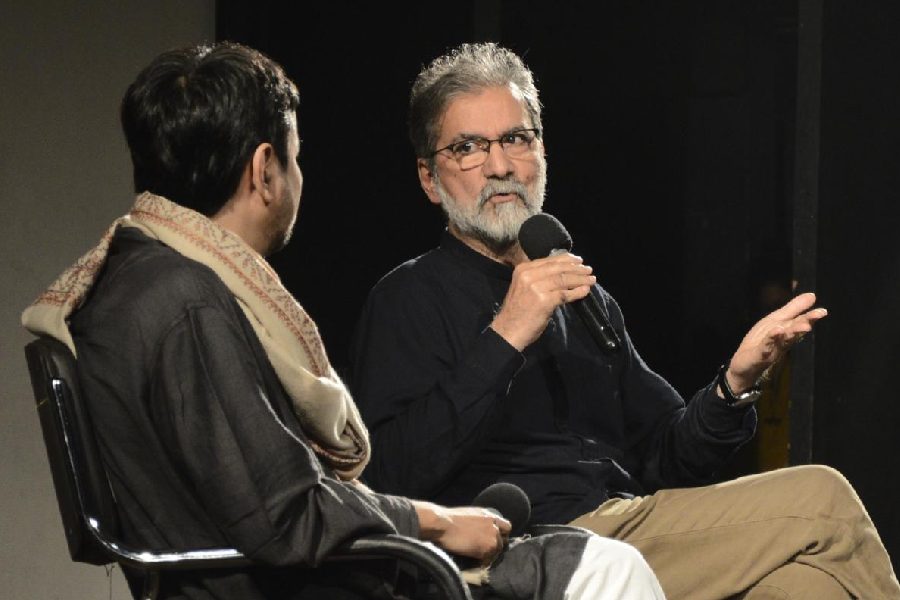

Yet, author and documentary filmmaker Sanjay Kak sees something positive in all these events, which he dubs a “profoundly moving act”. “It was as if people were gathering in the shelter of a film made 30 years ago, hoping that the storm will pass and that other worlds will still be possible,” he explained in his recent talk at a film festival in Calcutta.

Sometimes, audiences too shelter films, said Kak, giving the example of his own 2007 film on Kashmir, Jashn-e-Azaadi. “In the early days of its screening, the film came under attack by the guardians of national interest who decided that the film was anti-national and glorified terrorism,” he adds.

The reaction that followed was remarkable. With documentary filmmakers taking the lead, a set target of a hundred screenings was achieved. Colleges and universities, activist groups and NGOs, and even individuals hosted screenings.

“This ensured the fragile conversation around Kashmir was not stillborn and it did not stop,” points out Kak, who is a Kashmiri Pandit.

This interaction with the audience and Kak’s dependence on it is the thread holding this conversation together. I tell him how I watched his documentaries on YouTube minus the drama and Kak reiterates that he is old-fashioned and likes “the social context and the discussion that follows”. He stresses that he needs it, finds it fruitful. Kak says, “Twenty people watch a film, there is a conversation between those who like it and don’t like it, it leads to a third idea, someone picks on that and that may lead to a new film.”

Kak says he stumbled into documentary making. A chance research project and he was hooked. Starting in the early 1980s, Kak made documentaries every year or once in two years. The topics varied from Punjab — after the Khalistani movement — to the state of the Ganges to the Indian diaspora to Angkor Vat and were mostly decided by the funding available. Of course, all the funding came from some or other government agency — in those days that was the only thing available. All the films were nice, well-made films but “pretty mainstream”, says Kak.

He continues, “The period around 2002 is a most fecund period. The democratisation of technology gave a filmmaker the freedom to shoot what he wanted.”

This is when Kak was making his documentary on the movement in the Narmada Valley, against the building of the dam. Cameraman Ranjan Palit shot half of the film but Kak also shot parts when there was a financial crunch.

“I shot the film for a year, something that was inconceivable earlier,” he says. The film on Narmada, Words on Water, was the first of Kak’s truly political films though he claims he was still playing it safe. While most people start as young revolutionaries and mellow with age to join the mainstream, Kak has gone from middle-of-the-road mainstream to a rebel-with-a-cause.

His next film, Jashn-e-Azaadi, was even more hard-hitting. “I wouldn’t have been able to make Jashn-e-Azaadi if I hadn’t won an international prize worth Rs 6.5 lakh for Words on Water. I started the film with that money,” recalls the filmmaker. Jashn-e-Azaadi was sparked by a trip Kak took to Kashmir after a long hiatus just to introduce his teenage daughter to her roots. Now, he goes back at least twice a year and is currently trying to write a book of essays on Kashmir.

Kak’s last film was the one on the Maoist movement, Red Ant Dream. That was in 2013.

Why hasn’t he made any films after 2014? He replies, “Whenever I made a film, I was sure I could spend the next year showing it. Now those spaces are gone and which is what makes this (Kolkata People’s Film Festival) space so rare. If I can’t show my work in JNU or Delhi University or Jamia, leave alone in Gorakhpur or Indore, then who would I make that film for? Not for YouTube only because I want to be able to have a conversation with the audience.”