A band is blowing Dixie

Double four time

You feel alright

When you hear the music ring

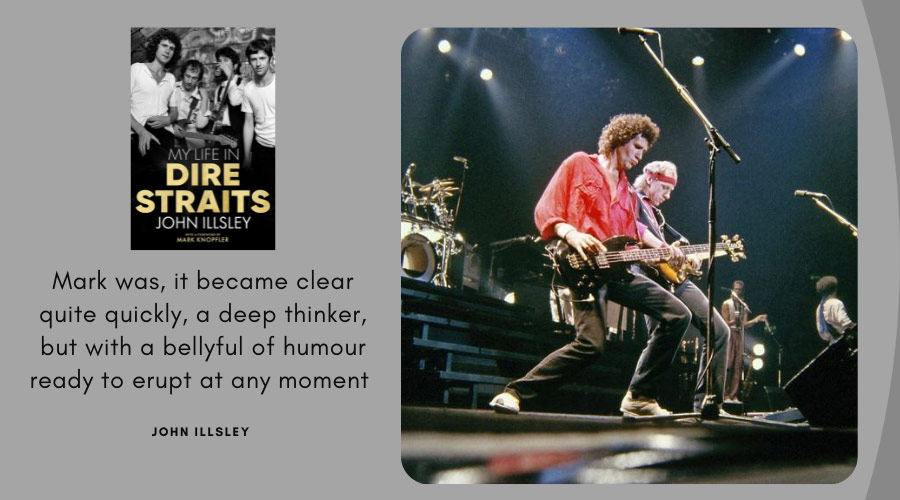

That’s the second verse from Sultans of Swing, the iconic song we now know was named after a jazz band Mark Knopfler had heard playing in a half-empty British pub. In spirit, the song is universal. It’s about quintessential bands, a group of friends that plays music for the sheer joy of it. Dire Straits was one such band in the UK of the late seventies. Playing alongside Mark was his brother David Knopfler, John Illsley and Pick Withers. Some of us grew up to their music, and still relive those days on Spotify or YouTube. Now, their story is out, courtesy John Illsley and his just published book, My Life in Dire Straits (Bantam Press/Penguin Random House).

At 72 Illsley, the band’s bassist and the only other founding member after Mark to stay the full 15-year course, recounts with understated humour and heartfelt love, their friendship, their ambitions, the discipline with which they went about things, and above all, the many people that crossed their paths and helped them achieve the pinnacle of success.

About his early beginnings in Middle England, Illsley writes: “…this is the world that shaped who I became, a small world that brought great comfort and security but a world that made me yearn for the distant shores of somewhere way more exotic.” That dream was fulfilled. But not before starting off as a bank clerk and then moving to a new job at a soup factory where one day he found his right thumb hanging off just below the nail after a cleaning accident _ ‘I am a guitar player. Put it back on please,” he told the surgeon who said he wasn’t sure whether to take it off or sew it back on.

Several misadventures later Illsley finds himself in London only to become friends with the guys who would soon become Dire Straits, the name that we also discover is anecdotally connected to Lindisfarne, a popular UK rock band of the time. In an interview with The Telegraph Online all the way from UK, Illsley talks about the music of the time, their incredible journey, the highs and the lows, and why, as Mark Knopfler says in a succinct foreword to the book, they were lucky not to have been teenagers when confronted with the professional music game. Excerpts:

TT Online: Congratulations on the book. Great fun to read, and it is very well written.

John Illsley: I am very pleased you enjoyed it. It’s quite difficult to get the right tone with some of these things, and I had to go back quite a long way to get my memory working again. I did have to check a few dates and names. I found that once I started talking about it, it started to flow and I managed to get it down in some kind of order.

Clearly, you enjoyed writing it.

It was interesting to go back and think about those days. What did it mean to me? What did it mean to other people? It’s (the book) a kind of celebration… of those incredible 16-17 years. I am very proud of what we achieved and I think it needed writing down. That’s why I wrote it. I think that for a lot of people who’ve been on that journey with us with the music, the concerts, the book would help them solidify some ideas about what it’s like from our point of view to do that. So, I tried to get that across. It’s about the music more than anything else and about the people who made that music.

I also realised that for us music lovers born in the mid-60s in Calcutta, India, and fortunate enough to have been born in houses with a record player, Dire Straits was a band we literally grew up with. First album, 1978, we were in Class VIII. By the time it reached us we were in senior school or college. Our musical tastes developed in sync with Dire Straits albums, growing as your music evolved.

It’s interesting because when I do shows now, the audience is full of all different ages, from sort of teenagers up to my age.. And those people in their 70s have been listening to the band pretty much ever since it started. So they have kind of like grown up with the music with the ever-changing people in the band.

John Illsley Facebook

How is it that you stuck on?

Mark (Knopfler) and I were there from the beginning. Things happen in life, and some people move on. It’s lovely when everybody comes on the same journey with you because I have done that with other musicians and artistes myself. I have followed Bob Dylan and people like Van Morrison when they first started because I love singer-songwriters. I think they’re the ones that tell the story best of all. In Mark we have somebody who could tell a good story.

Among some of the memorable lines in your book is the description of what music meant to you when you were young. You write, “… the music went deep and stayed deep, and lodged in there for good”. That is in the context of Elvis. Years later, Dire Straits would come out with the song, Calling Elvis, one of the most heartfelt and innocent tributes ever.

I think Elvis touched an awful lot of people quite quickly because I don’t think anybody had seen anything like what Elvis was doing. Somebody was able to write things for Elvis which excited people much more than anything else that was going on around them. We are talking about the time when the Sun Sessions came out around 1955-56. Go and listen to the very first album he did when he was _ Oh my God_ around 18 or something. They’re amazing. With Scotty Moore on guitar. I mean they (the songs) are very short but beautifully constructed. I think it was all recorded in a day or two. It’s completely magical.

I had the opportunity of talking to Keith Richards once and he joked how he still couldn’t play Scotty Moore’s solo on I’m Left, You’re Right, She’s Gone.

That’s All Right Mama is another one. It sounds simple but it’s very difficult.

Music connects. You and I are talking now, discussing music you and your friends made decades ago. And the best part, we still listen to those songs!

It is very interesting talking to people from all over the world. You discover that music is an extraordinary shared experience between all nations and it’s one of the few things that actually unite people _ as in that they are all sharing that music which makes it a very, very powerful force. And I don’t think it can be under-estimated how extraordinary that is on an international scale. I don’t think there’s anything else quite like it apart from pandemics _ I mean that’s the only other thing that joins the rest of the world together, but it’s not funny.

Let’s talk about Mark Knopfler, your friend and band leader of the Dire Straits. Your record collections were kind of similar, JJ Cale, BB King, Ry Cooder and so on. How much of their music influenced the band?

I think when you are fascinated by music generally you go and look into everything that’s there. Something speaks to you louder than other things. The very first time I heard JJ Cale was when I heard the track, Same old Blues, and I was like, ‘Oh my God, Jesus Christ. Who is this?’ So I became a follower of JJ and still am. It’s interesting that when I met Mark we shared the same taste in music. I think those people just spoke to us more clearly than other people. I’ll tell you what it is. It’s a certain kind of honesty about how you approach playing and listening to music. It does something to you. Like, you know, BB King. I mean nobody plays like that. People try and play like that but they don’t. And, you know, nobody writes songs like Bob Dylan. It’s just the way they are. They are just unique in a way. They would never see themselves as unique. They just see themselves as observers.

And their writing?

I think the beauty of writing songs that appeal to a lot of other people is like painting. Song writing is really painting a different sense of reality like a picture. A picture is really re-interpreting the world. And that’s what songwriters do for us. They interpret the world. And Mark is particularly good at that. I mean it was so integral to the band that song writing and guitar playing.

What made Dire Straits work?

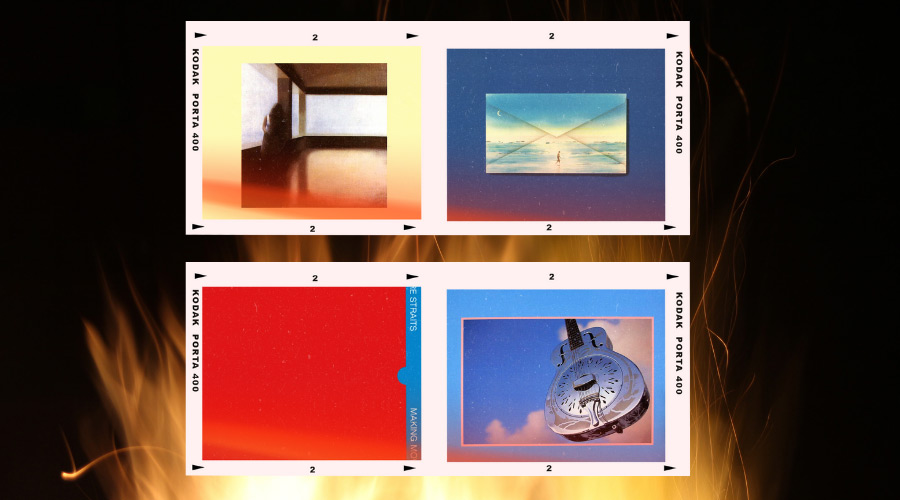

What makes bands is a number of things. There’s got to be a sort of sympathy between everybody in the band that makes some kind of sense together which creates a uniqueness. I think the band, pretty early on, had its own style. That’s what set it apart in some ways. Our first album, which I am now staring at behind your little screen, has songs that were dealt with in an incredibly simple way. Because they demanded to be done simply.

Explain to us the nature of collaboration in the band. How did you all contribute?

The initial flame, the idea, would come from Mark. He would play the song to me or somebody else on an acoustic guitar and I would just join in playing certain bass lines, keeping it very simple as I do. You gradually build up from something quite simple into something which makes sense as a whole. So everybody in the band has a role to play in how that music feels. And I stress the idea of feeling music because that’s a very, very big part of the Dire Straits sound. And I think that if other musicians had played those songs it would have been quite different. But the combination of Pick (Withers) on the drums, me on the bass and David doing his thing and Mark doing his thing (guitars) made that Dire Straits sound which everybody recognised from the first album. That was then carried out in the second album (Communique). By the third album (Making Movies) things were getting broader, bigger and more expansive with keyboards and synths. But everybody played a part.

Albums: Record label Phonogram had said they’d be “more than happy” if Dire Straits’ first album sold more than five thousand copies. “I never got to asking Johnny Stainze what planet he leapt over once it had passed the 20 million mark,” writes Illsley .

We know Mark wrote the songs.

Mark always came with the lyrics and may be just a few ideas on the chords or something. If you watch some of the early filming when we’re trying to get some songs together everybody is adding things, taking things away. So, it’s a community project in a sense. For instance, Telegraph Road came about _ and I talk about it in the book _ playing in Detroit. There’s a Telegraph Road there. Then Mark created this song about the birth of America as we know. All the segments in Telegraph Road were put together like a big jigsaw puzzle. There were a lot of shared ideas about what the song should be and we did it all in sound checks. When we got to the studio in New York to put the track down, we had a really strong idea about how it was going to work. But you still got to get the ebb and flow in the music, the shape of it, which is actually quite difficult. But because the band had been doing a lot of work together we had that natural sensitivity towards each other, if that makes any sense.

Absolutely. I must say though that for all the line-up changes that Dire Straits have been through, I seem to have felt Pick Withers’s absence the most in the later albums. He had a lovely touch to his drumming that give the songs a unique sophistication.

Yes… and a very lovely touch indeed. You are quite right. He just slotted in incredibly easily. I think that a lot of people would agree with you that the way he played the drums on the first two records was really, really special. And on Making Movies and Love Over Gold. Not many people can play Romeo and Juliet the way he played it. And there are not many people who can play Sultans the way he played it. It looks like it’s quite straight forward but it’s not. I owe Pick a great debt of gratitude for him showing me how a rhythm section can be so unifying and strong so everything else could build on top of it.

The song, In The Gallery, with its reggae intonations and staccato nature, is quite ‘unplayable’.

Laughs. I mention in the book how we were listening to quite a lot of reggae in the late seventies as well. So when Mark wrote In The Gallery after going to this art gallery in London, and I’d been mucking about with different reggae things on the bass, he said, ‘I think that might work with this song I’ve written’. And he brought out his guitar and played it. Yes, it’s an odd time signature as is Once Upon A Time In The West. It takes drummers quite a while to get used to that.

You all were very disciplined about your music, more so while playing live.

I think the reason that remained strong was because Mark and I had a pretty similar attitude to life and to how things should be. That’s what made us quite a strong team over the years. I don’t think we ever fell out about anything. I think something happened at one studio in New York and I think he said something and I went, ‘na na na it wasn’t like that’. And he said, ‘yes it was’. And I said, ‘I think you’ll find it wasn’t and it was like this, and he said, ‘oh yes, that’s right’. (Laughs). Yes, we did have a very strong work ethic and I think the reason we had that was because we’d had jobs before. You know, we weren’t 18 years old. We worked with all sorts of different people, and may be, understood a little more about the world. We figured this wasn’t going to work unless we put in a lot of time and effort into it.

Back in the day with Mark Knopfler and former Dire Straits manager Paul Cummins. Facebook

Mark, in fact, writes about that in the foreword to your book. He says you all were lucky that you weren’t teenagers then, which certainly helped you navigate the music business.

Yes, absolutely.

I want to talk about Live Aid (1985). I remember watching you all play on a black and white television screen _ our state-owned network aired some segments of the benefit concert aired across the world. There are a number of interesting details about it in your book. Most revealing is to learn that Bob Geldof, the initiator of the humanitarian project, was finding it difficult to get bands on board, and he was adamant on signing on Dire Straits as the headlining act. He felt that if Dire Straits did_ described in those days as the ‘biggest band in the world’ - then the other big acts would follow.

That is true. He was having difficulty having people to commit to his project. His project was obviously an extremely good one as everyone was aware of the problems in Africa. And he was finding difficulty in getting a big name. At that point of time Brothers in Arms was out and the band was on a big upward trajectory. I hate using the words, ‘biggest band in the world’. It doesn’t really appeal to me at all. But we were probably pretty big at that particular point of time. We were selling a lot of records and people were coming to see us. So he wanted us on board and I completely understood that. But we obviously couldn’t do it (headlining act) for reasons I explain in the book. We had 12 nights booked at the Arena at the same time. (Eventually, Geldof and Dire Straits agreed on a half-hour slot). It was an extraordinary thing to pull off, Live Aid if you think about it. And this is 1984 before the internet properly kicked off. Incredible.

The extended versions, and re-interpretations, of your songs when you were playing live are particularly fascinating. There’s an element of surprise, an additional instrument (the sax in Sultans) adds a new dimension to an already memorable track even while retaining the signature elements. It’s amply evident you all put a lot of attention to the re-arrangements.

Yes we did. You will know that live music is completely a one-off experience. …it is an extraordinary shared experience between the band, the musician, and the audience which is completely unique. Like an actor on stage, you feel this flow between the audience and the band which is magical. It’s a very powerful force. When you are playing a lot of live shows, you go to the stage and add and take away a lot of things keeping the original thing intact to make it more enjoyable as musicians to play it. So, for instance, on the Alchemy record, that 10 or 11-minute version of Sultans developed over several months and months of playing it. You know, make this a sax piece, then I would back out and not play for a while. Then, there was Alan Clarke’s keyboards, which as you know was remarkable like pretty much everything he ever did with the kind of orchestral thoughts he would have. A lot of those changes went on with him and Mark, and then, when you add other instrumentation in there, like pedal steel, you’ve got much more to play with and make it more interesting for yourselves and for the audience. The beginning of Romeo and Juliet, when we played that live, it was about three or four minutes of music before the song even started _ I think probably to give Mark a rest (laughs)!

Now for something you must be asked every day. Is there any chance of you and Mark coming together for a Dire Straits reunion?

Well, I would very much doubt it. We are all on different sort of trajectories now doing different things. I have a new album coming out in January. He is doing something too…

Four friends, including Mark Knopfler and Hal Lindes, at the book launch. Facebook

And you are painting.

Yes, I paint quite a lot. I love the different notions of communication. I love painting. It’s a very different thing from playing music or writing songs.

You discovered very late in life that your father was a painter too. It’s poignant that you too have gone into painting seriously, hosting solo exhibitions.

Quite right. We are all different types of people. I am not just a bass player and (a member of) Dire Straits though that’s what I am dealing with right now because of the book. But to be honest, in my everyday life, I don’t really think about that too much.

The music industry has changed. Some would say, there’s no industry any more.

I think you are being a little harsh. I think the music business will always be the music business. The way they operate has obviously changed immeasurably in the way that music is delivered. But you still got international bands, and people like Ed Sheeran or Billie Eilish who are reaching out across the world.

I was actually talking more about the musicians. Imagine what today’s young musicians are going through.

Well, there are those that have achieved and enormous amount… people like Cold Play, Kings of Leon. God I can’t think of the other names, but there are other bands that leave their mark and have got great following. I think the business side now deals with artistes in a different kind of way than they dealt with us in those days. They gave us much more of a chance to develop. I don’t think young artistes get much encouragement if they haven’t got a record… They are too impatient. They want the next big thing. They don’t want to hang around, waiting for something to develop.

I enjoyed your book thoroughly. But I also felt kind of sad. What you guys _ and a few other bands of the time _ did was pretty amazing. Four regular blokes getting together and making music, and doing a very good job of it; and somehow, landing the opportunity to project your music to the world. Now that’s a fairy tale. And it’s never going to happen again.

Music is still that shared experience. We all get a bit nostalgic about our time. I talk about the time when I went to see Jimmy Hendrix a couple of years before he died. That was a very short moment in people’s lives, but my God did he leave his mark. So I remember those times fondly, of growing up with all that power of that music. In the early 60s, which was when the teenager became a thing, when people were calling them teenagers, that went hand in hand with The Beatles, Rolling Stone, The Kinks, The Who, Elvis Presley and Chuck Berry. All that stuff came out within the space of six or seven years. I mean an incredible amount of energy hit the world. What a time to be growing up. So, I think for us who went through those times, it’s a lasting memory. It will never go away. I completely understand the frustrations you are expressing. The fact you will never have a Pink Floyd again.

Thank you John Illsley for talking us. And thank you for the music, Mark, you and the rest of Dire Straits. You made our lives so much better.

That’s very kind, and a wonderful sentiment. Very nice talking to you.