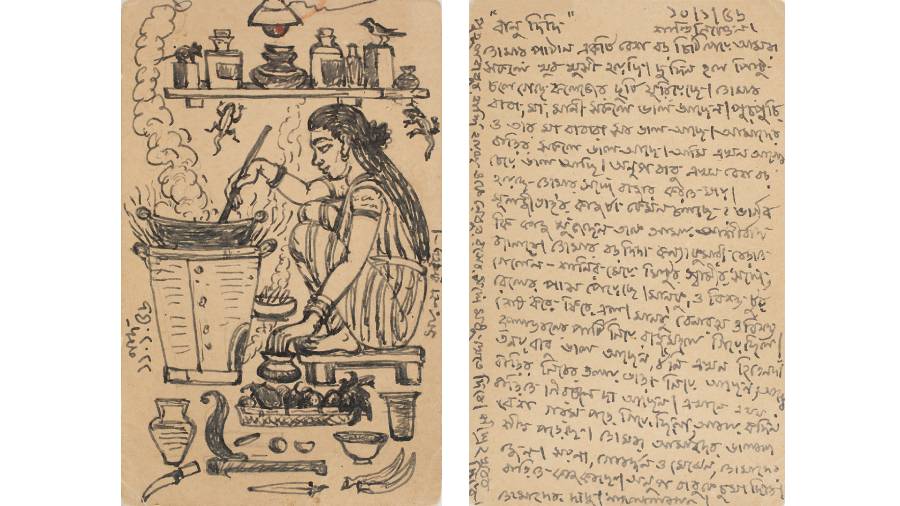

After Chameli Basu’s death, her daughter, academic-turned-politician Malini Bhattacharya, came across a stack of illustrated postcards in her mother’s almirah. They were from the artist Nandalal Bose and addressed to Bhattacharya’s grandfather Ramesh Charan Basu Mazumdar. The postcards had been mailed from various parts of India and abroad between 1918 and 1946. Sketches from Kurseong, from Darjeeling, from the Congress camp at Faizpur. The scribbles and sketches were Bose’s way of sharing his travels with his friend, who was the headmaster of a school and also an amateur artist, said art historian Tapati Guha-Thakurta.

The postcards survived countless shifts, the Partition and remained in her mother’s safekeeping till her death. Thereafter, Bhattacharya donated them to Calcutta’s Jadunath Bhaban Media Resource Centre or JBMRC. “I am sure my grandfather and parents would have wanted these to be in a place where art lovers can see them, research scholars can study them,” said Bhattacharya. The postcards were also part of an online exhibition titled “The Art of the Painted Postcard: Nandalal Bose and his Contemporaries”, hosted by JBMRC in collaboration with Ghare Baire museum of Calcutta, Delhi Art Gallery and Victoria Memorial Hall.

One family collection leads to another; in response to the exhibition, another set of Nandalal Bose postcards belonging to Mita Chakravarti was shared on social media. These postcards had been sent to Rama Chakravarti, Mita’s mother. Said Guha-Thakurta, the lead curator of the exhibition, “Rama Chakravarti had been Bose’s student at Kala Bhavan.”

In an online discussion on “Unpacking Family Collections: Personal archives and public art histories”, Guha-Thakurta spoke about how family collections are a kind of repository-inventory and archive that acquire new life when brought into the public domain.

In the discussion, poet, culture theorist and curator Ranjit Hoskote took audiences through his own family collections, many of which he himself discovered during last year’s lockdown. Hoskote said, “It’s a literary and mnemonistic practice. My parents were a young couple in the late 1950s. I have been looking at the things they collected.”

He showed family photographs, books that his parents collected, LPs, 45 RPMs, private letters, scrapbooks, albums, folders. “I have even looked into their kitchen drawers... And each object then began to talk about larger questions, how did this family in its own intimate and private space connect with a larger notion of public space, larger history, larger narrative, which might be an isolated case but not unrepresentative of a certain generation with cosmopolitan inheritance and Nehruvian connections,” continued the art curator.

Indira Chowdhury, founder-director of the Centre for Public History at Srishti Manipal Institute of Art, Design and Technology, Bangalore, spoke about her own experience of chronicling family history. She began with a letter written in 1964 by a Muslim man from Pakistan to her grandfather’s elder brother. She said, “When I found this letter, there was some talk in the family ‘Ah, you have found that letter’. It created a lot of heartache. I didn’t know why but I realised that this was about the ancestral home they had left behind.” The letter was about the village home in Merkuta. The letter writer raises the point that Bidyakut, which is near Merkuta, is full of refugees and he can no longer protect the property that belongs to the family. He proposes that the family sell off the property. Merkuta and Bidyakut are both places in present-day Bangladesh.

Chowdhury also showed audiences her aunt’s family album. The first page had photographs of her great grandparents in the centre and pictures of Saratchandra Chattopadhyay, Rabindranath Tagore, Ramakrishna Paramahansa, C.R. Das, Subhas Chandra Bose, Jawaharlal Nehru all around them. “The album was a way of remembering not just her ancestors but also the people of the land and the land itself,” said Chowdhury.

JBMRC has photographed and documented the private collection of Radhaprasad Gupta, an early 20th century collector. It includes Kalighat paintings, Bat-tala woodcut prints and chromolithographs from the Kansaripara and Chorbagan art studios. Guha-Thakurta talks about Parimal Ray’s collection as well, which is the largest single private repository in the city that was fully documented by the JBMRC archives. The octogenarian’s house is a museum of popular ephemera — from matchbox labels to enamel street signage to cinema posters.

JBMRC has tapped into the art collections formed over the mid and late 20th century by several Marwari business families in the city. Guha-Thakurta spoke about Nandalal Kanoria, who had in his possession paintings by English artists George Chinnery, Tilly Kettle and Thomas Daniel and oil paintings on mythological themes by anonymous artists — known as Early Bengal Oils. “But the surprise was to find works of Bengal’s modern masters,” said Guha-Thakurta.

She continued about how the centre has in its visual archives documented and catalogued works of modern Bengali artists such as Gopal Ghosh and Gobardhan Ash from their family collections before the works entered the art market. Guha-Thakurta added, “In our archives, there are collections of many artists who have not been central to the history of modernism or even to the history of how we write about modern art. The collections are also a public resource for writing newer kinds of art histories.”