This particular brand of magic, it can happen anytime. You are out on a street that is a tangle of honks, wheels and irritability. Suddenly, you look up and above the wires, poles and jagged silhouettes of buildings, the sky is waltzing with orange, gold, pink and a blushing lavender. And you hum Roz shaam aati thhi, magar aisi na thhi, roz roz ghata chhati thhi, magar aisi na thhi.

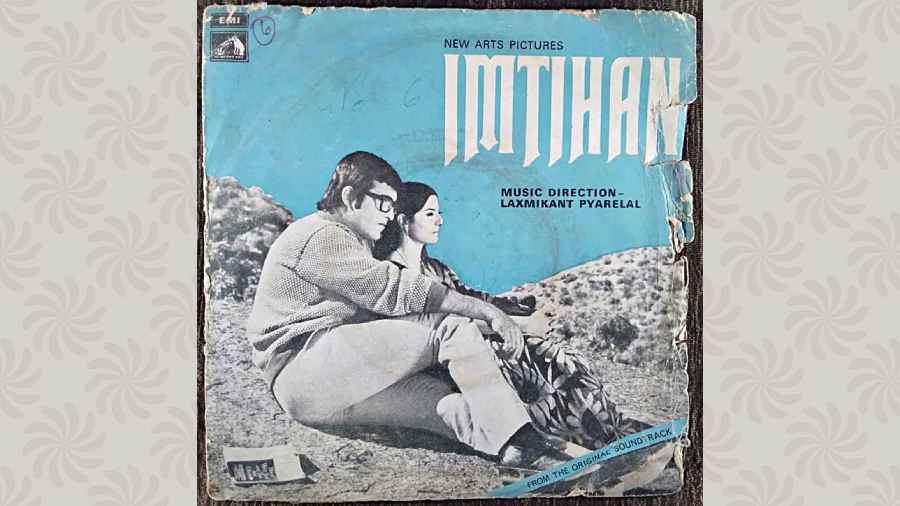

You’re probably not thinking of Laxmikant-Pyarelal, Majrooh Sultanpuri or Lata Mangeshkar. Much less of the almost-forgotten 1974 film, Imtihan, directed by Madan Sinha, which was a loose remake of To Sir with Love, or its leads Vinod Khanna and Tanuja. But you’ve hummed on an extraordinary evening.

For me, Hindi film songs are the best part of many things — most often better than the films themselves. They are perhaps the best thing about my city, Calcutta’s soundscape. They are my go-to for nostalgia or passion or perspective. Sometimes just an excuse to soak in the music in all its eclectic diversity, be it Hindustani classical or Carnatic or folk or jazz. Sometimes, a conscious effort to understand how complex poetry can be made so miraculously simple as to be set to music.

A good Hindi film song can be as simple as a mood-upper. But it can also be many things. Take listening to Roz shaam aati thhi, for instance. It’s a song of wonderment, of the stirrings of love that make one look at the world with new eyes. The inimitable Lata, whose voice captures the ache of spring, makes sure we know it is a song of a young woman’s desire. So far so good.

But here comes the whammy. It was written by a man and composed by two men.

How did Majrooh Sultanpuri, a man in his 50s at that time, know the words a girl awakening to love and desire might use? How did Laxmikant Shantaram Patil Kudalkar and Pyarelal Ramprasad Sharma know the soundscape of her deepest feelings?

Majrooh writes for the woman — Dagmagati hoon main, deewani hui jati hoon main, deewani, deewani, deewani... deewani hui jati hoon main. Laxmikant-Pyarelal and Lata infuse in this part a breathlessness; it lends the lovers’ sunset outing a dreamlike quality. The repetition of the word deewani, the artful use of the present continuous make her ecstasy urgent and immediate, the self-realisation of losing her own self a poetic oxymoron no less.

And then comes the refrain — which is a question that shows her surprise, because her feelings are still very new and young — Yeh aaj meri zindagi mein kaun aa gaya.

How did Laxmikant and Pyarelal know how to make her words sing? In the 1970s, Lata’s sweetness and range made her the obvious playback choice for a romantic number of a leading lady in Hindi cinema. But it is not that simple. How did the music directors know that the elegant French horn and the conga, a slim-hipped drum from Cuba, which they used in the orchestration, would help Lata’s vocals soar? In contrast, the refrain is slow and dramatic, and gives the musical effect of clouds piling on clouds. It echoes across the landscape and the song and the cinematography together create a haunting synaesthesia that gives the song a longer life than the film.

This also happens because of an alchemy as glorious as that sunset. The song ceases to be Lata’s or Majrooh’s or L-P’s or even that of the character that Tanuja plays in the film. It becomes mine and yours. It pours out of ramshackle shops in alleys, it is a part of karaoke evenings at upscale weddings, it is remembered during sunsets shared and solitary, it is dissected in heated addas about who’s better, Majrooh or Sahir or Kaifi or Shailendra, L-P or Pancham, Lata or Asha. It is a song for endorphins during a stressful commute or the good old antakshari. Forty-eight years after its birth, it is still heard and hummed.

It’s just one song, one among countless songs of Hindi cinema where characters get to sing their most profound or playful or passionate conversations. In a Hindi film, a song can be anything from desire to denouement. One can argue it is an artifice, mediated at so many levels, and in many cases harms the cinematic narrative.

All said and done, the Hindi film song is possibly the most acceptable cultural shorthand we have in our country today. It bridges all kinds of divides. You hear the strains of your favourite Hindi film song and feel all warm and fuzzy inside. Which is saying a lot, given the power of cancelculture and bigotry today.