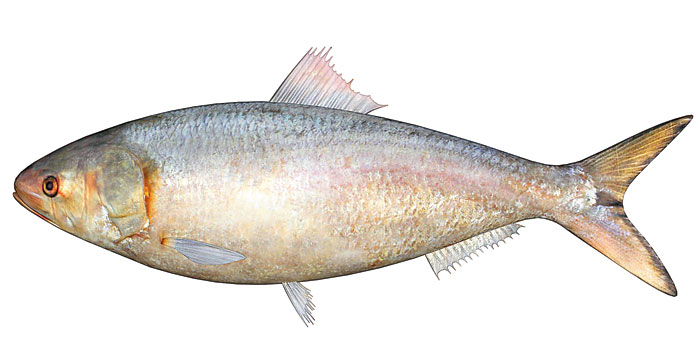

Rains alone do not a Bengal monsoon make. There must be the ilish — or hilsa — on the plate, redolent with its unique goodness. Ilish fried along with its roe and served with the oil it is cooked in; ilish steamed; ilish doused in mustard gravy; a light ilish jhol flavoured with green chillis and black cumin; the fish head cooked with kochur shaak (colocasia) or cabbage…

Rains and ilish, ilish and rains, the two be entwined. As one fisherman explained it with poetry and precision, when the ilsheguri brishti or monsoon drizzle combines with the pubali hawa or easterly breeze, the ethereal ilish swims out from the sea and into the sweet waters to spawn. That is also when the fisherman’s treacherous net closes in on the silver fish.

I am supposed to travel to Digha for the first big haul. The plan is to pick a single fish and track its journey from catch to kitchen. But this year the rains are whimsical and so is the ilish. Every time I call the auctioneers at the Digha Mohana market, the wholesale auction market in east Midnapore, they report: “Dekha nei go… No ilish sighted yet.”

Finally, on August 13, my phone trills awake at the crack of dawn. The voice at the other end, excited and urgent, belongs to Bappa, a sorting boy at Digha Mohana. He is saying, “Dekha giyechhe. Ebar aashun… The ilish has been sighted, come now.”.

Moumita Chaudhuri

10am, Day 1

Shankarpur Fishing Harbour

This is the fishing harbour that feeds the auction market in Digha, which is 15 kilometres away, the jetty which corrals in the ilish from the sea. Facing the jetty is a curious contruct. A longish hall, doorless, with an asbestos roof. It is packed with fishing nets, some heaped, some spread out, like fine sewai. There are rubber balls that are used to keep the nets afloat, crates and pumps. This is a storehouse-cum-repairshop-cum-resting area for those who work on the trawlers. The ice factory beside it groans continuously; it churns out loads and loads of crushed ice which will be used for storage. On the shore, a fleet of trawlers is lined up. Most of them are unloading the catch. Men in tees and shorts are shovelling fish onto fair-sized crates.

Jagannath Bera is a fisherman who is just back with a catch. He looks worried as he examines a sky blue net. He says, “Ilish is the only way of earning a fair bit of money. A trawler owner earns Rs 6 lakh or more during the entire ilish season which lasts about three to four months. We make Rs 2-3 lakh. And that keeps us going for the rest of the year.”

Ilish is a deep-sea fish. Bera tells me how fishermen have to sail for a good 50 to 60 hours before they can find good catch. “Unless the water is as deep as 40 or 50 bam (fishermen’s unit of measure; one bam equals 12 feet), we will not find ilish,” he says. According to him, after a trawler sails into sea, it stays there for a week or 10 days before it returns with its booty. “The trawlers are fitted with adequate storage facilities to ensure that the haul remains fresh and fine,” he adds.

Moumita Chaudhuri

3am, Day 2

Digha Mohana Market

The Bengali poet Buddhadeb Basu once wrote a poem titled Ilish. It goes: “Ratri sheshe Golande andho kalo maalgaari bhore/Joler ujjwal shoshya.” Meaning, at night-end the blind goods train pulls into Golando with the waters’ sparkling harvest. The Digha Mohana market is 250 kilometres from Calcutta. This is where the ilish arrives after being harvested from the waters at Shankarpur.

It has rained through the night, but not enough to dampen the mood at the auction market. One by one the chhota haathis, or small lorries, and charso saats, or medium-size lorries, pull into the road leading to the market. Men in raincoats and plastic sheets drag out crates loaded with fish — pomfret, pabda, khoira, telapia, pakhna, bhetki — off the truck and onto van rickshaws.

Where is the ilish? I get impatient. “The auction for the sea fish will happen first. Ilish will follow,” one wholesale trader explains. Clearly, ilish is a category by itself. The trader won’t give me his name, only his trademark. Everyone here goes by a trademark instead of first name or last. Trademarks sound like this — AD, GNFT, DB, KD, NP…

Suddenly, a voice cuts through the pitter-patter of rain — “Panchsho taka, panchsho taka, panchsho, panchsho, ponchis, ponchis, tirish, ektirish, ektirish, ektirish… Five hundred rupees, five hundred rupees, five hundred, five hundred, twenty five, twenty five, thirty, thirty one, thirty one [in these auctions, the base price is not repeated after the first few times].” And the auction begins...

5.30am, Day 2

Digha Mohana Market

The first lot of ilish streams in in blue crates. Hungry pairs of hands pass them, shuffle them, and segregate them by weight and size. “The ones below 600 grams are stacked together, then those weighing between 700 and 900 grams. Anything above a kilogram is set aside,” explains Batakrisna Patra, a wholesaler. I recall what a trawler owner from Shankarpur had told me — an ilish weighing two kilos and seven hundred grams sold for Rs 7,200 two days ago.

Patra has been in the business for over three decades. The septuagenarian says, “In 30 years I have never seen such a poor catch. Today, I got only 700 kilos of fish; tomorrow, I might get nothing. In the old days, on an average, we used to sell one tonne or 1,000 kilos of fish every day during ilish season. This year, we are selling barely 100 kilos per day.” This is impacting the price. A 400 gram ilish is being auctioned for Rs 600-700. “The retail price would be very high,” he says.

Basudev Burman seconds him. The 29-year-old has been buying fish at the auction market and supplying it to markets in Calcutta. He tells me he is not venturing into the ilish business this year. “I have to buy at Rs 600 per kilo and sell for less in the retail market. It is a complete loss,” he says.

But he is willing to share some of his ilish biases with me. He says, “Digha ilish is the best. The fish we catch here is rounder and pinkish. The ones that come from Diamond Harbour are longish and do not taste as good as the ones sold here.”

Ilish aside, the market is bustling. And then the moment presents itself. I identify a 700-gram ilish, which Patra tells me has been purchased by a wholesaler, Biplab Burman, who supplies fish to Koley Market in north Calcutta’s Sealdah area. This is the fish that I am going to tail. I name it Buddha.

Burman will be sending the fish to Koley market that night. I ask him if he can pack it separately, so I can identify it later, and he tells me that is not possible. He says, “It will spoil easily if it is not packed properly with loads of ice.” Later, however, he places a sal pata, a leafy marker beneath the fish for identification. Nevertheless, as the fish is loaded onto a truck, I am sure I have lost Buddha.

Moumita Chaudhuri

5am, Day 3

Koley Market, Sealdah

Koley market is in a perennial state of bedlam. On a wet August morning, it is several times worse. Mud and slush impeding the movement of vehicle and humans alike. There was no sign of Burman, but Buddha had reached.

From the looks of it, at Sealdah, the supply of ilish is pretty abundant. “But these are not from Digha,” says one dealer. He points to a crate of pinkish fish and tells me they have travelled from Chennai, a darker variety is from Mumbai, another one is from Odisha. There are a couple of fair-sized fish weighing over a kilo or so from Diamond Harbour. “The supply is not up to the mark,” repeats a dealer who is sorting fish for the auction.

In time, Buddha goes up on the scales. The man who bids and buys it tells me with a swag, “My name is Bobby. There are three of us, famous Bobbys. The actor, Bobby Deol; the mayor, Bobby Hakim; and myself.” He says, “I am going to take it straight to Gariahat market,” as he loads the rest of his purchase onto a small lorry. “Ilish is very expensive this year. The ones, which are just about 500 grams, are being sold at Rs 650 to Rs 700. And I will have to sell them at Rs 900 or so,” he adds.

Moumita Chaudhuri

9am, Day 3

Gariahat Market

The south Calcutta fish market is only reasonably crowded. I walk past insistent retailers crying, “Edike, edike... this way, this way,” and walk straight up to Bobby. Buddha, now on a banana leaf, is smiling.

A woman in her late thirties arrives and after a fair bit of examining points to Buddha. As she makes her purchase, Nibedita Bhattacharya says, “It is a relief to know I am buying a fish that has been caught this season. The last one I bought was definitely from the cold storage. No taste, no smell.”

Basu wraps up his poem thus — “Tarpor Kolkatar bibarno shokale ghore ghore/Ilish bhajar gandho… Elo barsha, ilish uthsab.” Meaning, the grey city morning erupts with the fragrance of fried ilish, announcing to all the onset of the monsoons and the beginning of the ilish festival