Last year, an incident at a swank mall near Calcutta’s Park Circus area triggered the debate on inequality of heat. Fed up with nature’s rage and frequent power outages, residents of slums contiguous to the mall picketed it. They knew it was owned by the same group that owned the discom responsible for the city’s power supply.

“Those who contribute the least to global warming or greenhouse emissions are the worst sufferers of climate change,” Ulka Kelkar, an economist with 24 years of experience in climate change research, told The Telegraph.

She added, “While the rich have access to gadgets to minimise their discomfort, the poor with no such access are deprived of the natural assets of green and blue by the rich to create their own comfort zones of air-conditioned malls and offices.”

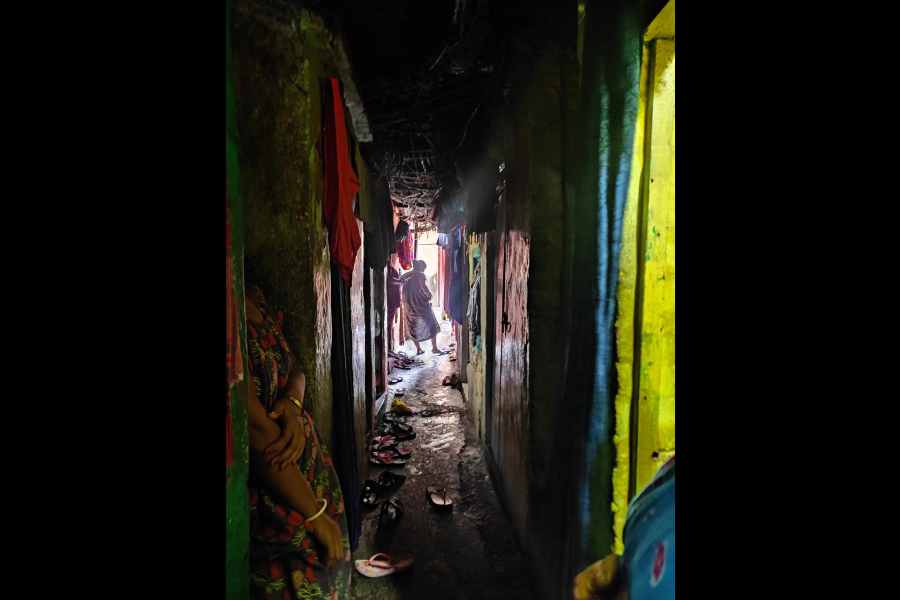

Peyara Bagan slum

The Delhi-based Centre for Science and Environment recently published a heat tracker for Calcutta. It recorded annual and diurnal trends in temperature, humidity and overall heat index from 2001 to 2023. The data is supposed to help in the planning and implementation of heat action plans, specifically for the city to cope during summer and prevent heat lock-in.

Avikal Somvanshi, who is co-author of the heat tracker report, says, “Calcutta is quite dense and tightly built. It is already saturated in terms of people density as well as ‘built structure’ as compared to Delhi or Hyderabad. This is creating urban heat islands.”

An urban heat island is a patch that is several degrees warmer than its surrounding peri-urban or rural areas. Urban slums would qualify as heat islands.

Peyara Bagan slum in south Calcutta.

According to NGOs, experts and many others in the know, of the 4.5 million people living in Calcutta, about 1.5 million live in slums. The temperatures of these are four to five degrees higher than the surrounding areas and for no fault of their own.

Somvanshi says, “The difference in average day and night-time temperatures is six degrees in Calcutta, while it is double in other cities.”

There are two major contributors to what is known as the heat island effect.

Contributor 1. Concretisation. Brick and mortar absorb heat during the day. During the night they release heat. The amount of heat the concrete releases is significant enough to heat up the city.

Contributor 2. Waste heat from air conditioners and tailpipe emissions. This heat gets trapped between tall buildings. “At night, it is this waste heat that is very big, so big that it is keeping temperatures way higher than it should be. The city is burning on its own during the night,” says Somvanshi.

And while nature does not discriminate, who is bearing the brunt of this man-made oppressive heat? The answer would be the urban poor. Earlier when one walked down the bylanes and back lanes, typically, there would be a cool breeze blowing through them. Now with the air conditioners on the balconies and verandahs, the exhaust heat fills up these back lanes.

According to Somvanshi, the urban poor who would take advantage of nature and the natural way of cooling are now being deprived of that by the rich who are polluting the breeze. He says, “Waste heat is getting dumped on the slums.”

It is not as if nothing can be done to mitigate all this. Kelkar talks about how in places such as Ahmedabad and Kanpur, climate-resilient housing with white roofs is used to reflect out the heat. In Bihar, where there is barren land, people are being incentivised to plant trees.

Somvanshi says the exhaust has to be managed using technology. Besides, cool roofs, deconcretisation, disallowing heat-trapping structures of glass and concrete, planning infrastructure and looking for technology to recover heat are some of the ways to cool the city down.