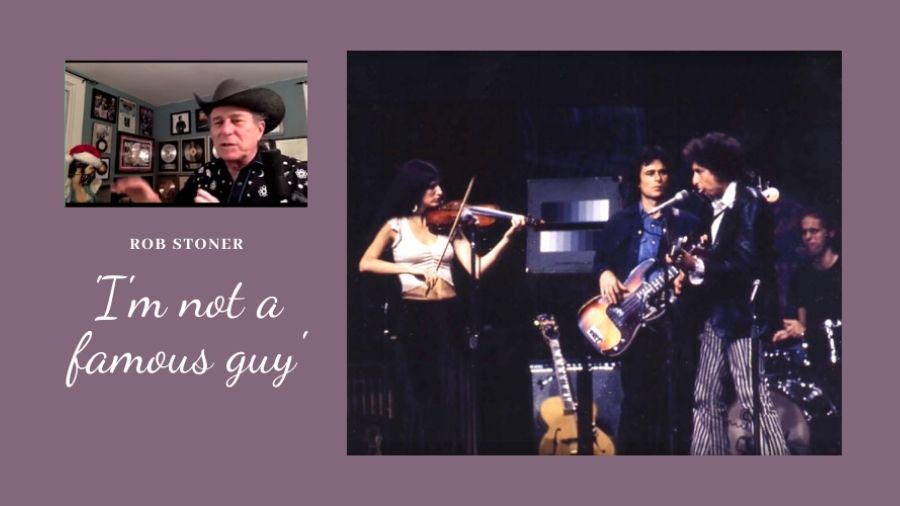

If there was a list of famously unknown stars in the galaxy of rock music, he would surely be on it, shining bright. You can hear him singing harmony in American Pie, play bass in the Bob Dylan exotica album Desire and see him sing alongside Dylan in the Rolling Thunder Revue, a Martin Scorsese film that is a mischievous pastiche of archival footage and wild fiction capturing the spirit of 1975 America with electrifying performances by Mr Zimmerman and such eminences as Joan Baez, Joni Mitchel and Allan Ginsberg along with a flurry of troubadours that were part of the travelling variety show.

Rob (Rothstein) Stoner is a natural. A brilliant musician whom Dylan, known for his uncanny ability to zero in on real talent, chose as his band leader/musical director for the tour right after he had recorded Desire with a spartan collective of musicians that also included Scarlet Rivera on violin and Howie Wyeth on drums. “It was an amazing accomplishment and we did it with just a few days of rehearsals,” Stoner tells me over Zoom from New York in an extensive conversation spanning his …decade-long career as a top-draw, but low-key session musician. He has played for and with them all, from Don McLean and Joni Mitchel to Bruce Springsteen, Ringo Starr a host of folk singers of the 60s and 70s like Phil Oaks, Joan Baez and Pete Seeger. “I was well-known in those circles,” he says in a matter of fact tone. “I was in New York backing up singer-songwriters. I had already played and sang on the record, American Pie. I was the bass player and harmony singer on that record. And so, everybody knew me from that because that was a very successful record.”

No wonder then Bob Dylan picked him up. “I met Bob Dylan several years before I started working with him. We got along well, and we agreed that we would do something in the future,” he reminisces but reveals, with tongue firmly in cheek, that he didn’t think much of that promise at the time _ “Sure, I'll believe that when I see it”. Yet, it happened and Bob Dylan did call Stoner. The Desire album was his first project with him in the summer of 1975. Dylan was looking for a new group and as it so happened, he had summoned a whole bunch of musicians including the likes of Eric Clapton to work with him, but he wasn’t getting anywhere with the recording even though he had worked out all the songs. Ultimately, it fell on Stoner, who had been called in as an independent observer, to do the straight talking.

Desire- The album cover

“Well, I could see right away when I showed up at the recording studio that everything was disorganized. And Bob Dylan was so focused on his music, he didn't see all the confusion around him. I, however, saw this as an objective observer and asked Bob to send all these people home. ‘You're wasting your time. You're never gonna get results’, I told him.” Finally, at Stoner’s suggestion, Dylan agreed to a simple line-up of guitar, bass, violin and drums, a combination he was so intrigued by he agreed instantly _ ‘Oh, what the hell? I’ll try it’.

Stoner knew that Dylan liked spontaneity. He was not for doing take after take. He’d rather do a run through of the song once or twice and if it’s good enough, stick with it. “So sort of on a dare, he took up my offer. But I could hear the sound we wanted for the album in my mind before the band ever assembled. I knew how my drummer (Howard ‘’Howie’ Wyeth) worked. I knew Scarlet Rivera (violin) sounded good. She has sort of a raw quality which complements Bob's raw quality. And that I could just fit in between all these cracks and make the thing sound good. I was the glue that held it all together.”

The net result was Desire, one of Dylan’s most distinctive albums about outlaws, a heavyweight champion wrongly accused of murder and tomes on marriage and failing relationships, a tribute to his soon to be ex-wife Sara. It also had Emmylou Harris and Ronee Blakley on additional vocals. “We instantly started getting results. We did about 10 songs. The first night we did the entire album plus some outtakes that they used later such as Abandoned Love, Golden Loom, Rita May,” Stoner recalls and describes the omission of Abandoned Love from the album as a “sin” _ “It was so silly because Joey is like a long, boring song about an outlaw.” He is also miffed, although he is old enough (75) now to be able to laugh about it, that the album credits did not mention him as a harmony singer. In fact, when they recorded Abandoned Love, Emmylou Harris had gone and it was Stoner who had to do backing vocal duty too.

His natural prowess as a singer, lead as well as backing, has been documented by no less than the late American author, actor, playwright Sam Shepard, who while reviewing a Rolling Thunder performance wrote, “Rob Stoner grafted harmonies onto Dylan like a Siamese twin.” Pleased as he is about that, Stoner, however, bemoans that harmony is a “lost art now” and goes on to narrate a lovely story that reinforces his musical abilities. Not many know that the Everly Brothers did a version of Abandoned Love, and they fashioned it on the original. “We were trying to be like the Everly Brothers and when they recorded the song and used the exact harmonies that Bob and I had sung, I was happy about it.”

So how does he do it? Does it help that Stoner also plays the bass? “It's all about listening to the lead singer at all times and watching his face. You watch when the mouth starts to change shape to make the next syllable so you can anticipate what's coming. It's really about being alert and sensitive,” he says and goes on to stress that just because someone is a good singer, it doesn’t mean he/she will also be able to sing harmonies. “I am lucky I can sing both. In the movie, you can see me on the same mic singing with Bob sometimes.” Many would agree that singing while playing the bass is difficult, but is made to look easy by the pros. Consider Paul McCartney, Jack Bruce to name a few. Now, add Rob Stoner to that little list. His felicity with the instrument is nothing short of phenomenal. Listen to One More Cup of Coffee, the live version, to get the drift, and be amazed. “It just comes naturally to me. I can play the bass in my sleep. It’s so easy to me,” he says, not boasting, but telling it like it is. “I’m also a piano player and a guitar player. (But) the bass to me is like a toy. I just do it autonomously, and that gives me the freedom to think about the singing.”

The Rolling Thunder shows were musical milestones, the array of guest stars (Roger McGuinn, Ronnie Hawkins, Ringo Starr and many more) adding zing to the stellar performances. And Stoner reveals how meticulously these were mapped, courtesy Jacques Levy, Dylan’s co-writer on the Desire album songs, and an accomplished Broadway producer. “We did it with just a few days of rehearsal. It's because Jacques Levy was so smart about theatre. He and I would stay up all night, thinking about how to plan this, like, this guy is got to be off the stage, and this guy is gonna come on. We had planned out every song. Like a stage play. This was like 30 rock concerts in a two or three-hour period.” The shows were a sonic and visual treat, what with Dylan’s face-painting which the others quickly picked up on. Stoner remembers it all, at times right down to the songs. His narration is dramatic and detailed, mirroring the energy of the shows.

“Before Bob came on stage, there were already five acts. To open, all the members of the band did our own songs. I did one, Mick Ronson did a song, T Bone Burnett did a song, Receiving Souls. Then we had Ronnie Blakely, who was very well known because of her part in the movie Nashville, come out and do a song. Then Jack Elliott, who was a big influence on Bob Dylan and Woody Guthrie, came out. Then Roger McGuinn would come out and do all his great hits from the Byrds and we’d back him up. And then Joan Baez would come out and she'd do some songs. We’d leave Joan alone without the band. And she would introduce Bob. Bob would come out and they would do a couple of duets. After they finished their duet section, Joan would leave. And this left Bob alone on stage, and he would do something by himself. Then, we'd bring the musicians back and do like a half-hour of electric music with Bob and that would really rock it… and in the middle of the electric music, most of the musicians would leave the stage and it would just be the Desire band, which is Scarlett, me and the drummer. And we had a percussionist too. Then we'd do a big, loud finale when we do Isis. (You can see) Bob and I are on the same mic screaming away... So, now there's an intermission for a half-hour, and we come back and we do basically the same thing except with different personnel.”

Yes, 30 rock concerts in three hours.

To Stoner, Dylan counts most for his poetry, for which, he believes, he plays music, using it as a frame to help people listen to this statements. “I mean, he's a good singer. He knows enough on his guitar and piano to just play his songs. The guy's not a virtuoso player. That's not his thing. His thing is the words and the statements, and so everything else he does is just to serve those particular ideas of what he has to say.” But unlike Dylan, whose voice is now “so tiny compared to how it used to be”, Stoner’s managed to keep his singing voice going, a nice ‘n easy mix of Elvis and Jim Morrison, an assessment he seems to approve of. “I always thought Jim Morrison took a lot from Elvis. I thought he sounded like a kind of a lounge singer Elvis Presley. And so, thanks man.”

Aside of Dylan, of all the musicians he’s worked with, and among the few we are able to discuss, Stoner is perhaps most affectionately respectful about Joni Mitchell with Levon Helm and Richard Manuel of The Band coming in very close. “There’s nobody remotely like Joni Mitchell, just like there's nobody like Bob,” he says. “There are certain people whose art has lasted for decades and decades. These people are different. And when you talk to them, you get a sense that these people are endowed with such superior intelligence… In fact, most superstars I've met are like that.” Levon of course was a close friend, the two hung out in the studio he and Robbie Robertson had set up in Santa Monica, called Shangri La. “Our wives were also good friends. Levon would come to my shows and sit in and play drums. And his singing was amazing too,” as was Manuel’s. “Yeah, such a tragic life. The guy was such a sad guy. But he had an amazing gift. And you know what's amazing to me is that in The Last Waltz _ everybody talks about what a great movie it is _ how come you can never see Richard Manuel,” he jabs in, airing what rock aficionados have always maintained was an unforgivable lapse on the part of the great Scorsese to not devote enough footage to Manuel in the film that chronicles The Band’s start-studded farewell concert on November 25, 1975, at the Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco.

In summation of Rob Stoner as a professional musician and singer it is his innate oneness with music that stands out more than anything else. Even more than his cavalier attitude towards fame. He knew as a child that when somebody sang a melody to him, he could go to the piano and play it right away. He was also smart enough to nurture that natural ability. “…if you get formal training, then you can develop that ability to a higher art and be able to just mimic anything you hear, and maybe add your own little taste to it. So, that was the skill which I utilised,” he concludes. So New Yorker Stoner could well be part of the Nashville, Tennessee, musical talent pool, the ones who studios use to conduct “head sessions” where the multi instrumentalists get to hear a new song _ in their head without a written score _ and figure out how to play it, hours before recording it with the star. As a session musician, Stoner is the guy they call up to play with no rehearsal. “You just show up. American Pie? I never heard the song in my life. I showed up. He (Don Mclean) played us the songs. We sat down and played it right away.” Bob Dylan? The same. That’s the reward, not that Stoner is seeking any.

These days Stoner is doing music videos of his own, jazz, blues country, and posting them on YouTube _ his Facebook is full up and cannot accept any more friends. At other times, he’s taking master classes on Zoom. “It’s not inexpensive, which keeps the numbers down, but is a good way to have some money coming in.” That’s because he’s still not comfortable going out and playing concerts. “Because I'm not a famous guy. I can't draw a lot of people. I can fill a small room of like, you know, 100 people or something. But that's kind of a small or medium-sized club. And those places are just unsafe, there's not enough ventilation, especially now in the winter,” he adds with disarming candour and rationality. Ask him how it feels to be not famous and he calls it a strange combination. “But you know, there has to be somebody who does the hard work that makes the big guys famous. For every guy that's famous there's like 50 or 100 people behind them doing the day-to-day work. And they don't get the credit. We're the guys who really make the thing happen, the guys behind the scenes, the guys who write the arrangements, the guys who rehearse the band.”

That’s Rob (Rothstein) Stoner, speaking out for generations of famous unknowns in the service of a timeless melody. Amen.

Rob Stoner (in a red shirt) playing bass to the right of Bob Dylan on the Rolling Thunder Revue in 1976 at the University of Florida Stadium in Gainesville. Photo by Frank Beacham ©1976