After the screening of his 163-minute director’s cut of The Tin Drum at the Kolkata International Film Festival earlier this month, Volker Schlondorff applauded the audience of around 300 who had gathered at the 500-seater Nandan-I for being “the last admirers of art-house cinema”. He described Calcutta as a melting pot of cultures. Much like Danzig in Poland where Guenter Grass’s path-breaking novel is set in. There were Germans, Kashubians and even Scandanavians.

“When Hitler came to power he spoke of getting rid of all the different nationalities in the city (Danzig) to make it one city with one culture. Strangely enough he got a lot of support for this because the majority of the population was lower middle class,” Schlondorff told the audience. “But political parties of the time were focusing either on the proletarians or on the capitalists of the bourgeoisie. The lower middle was the neglected class and that’s where the Fascists got their votes in those days _ as they do today.”

The audience clapped hard in kinship with someone who had spoken its mind. Calcutta showed its hand. So what if only 300 of us were there.

I met Schlondorff a week later over coffee. The Sorbonne-mentored German filmmaker, who is revered alongside fellow stalwarts of the 1960s’ New German Cinema (Warner Herzog, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Wim Wenders), is in his 80s now. But he has a meticulous memory, narrating the time Grass cooked eel for him, explaining why he didn’t quite understand the fuss about Grass’s Waffen-SS revelation in Peeling the Onion, and Grass’s difficult relationship with Salman Rushdie.

Excerpts of the conversation.

Oskar with his drum, a still from Volker Schlondorf’s film. Courtesy Press note issued by Janus Films

What did The Tin Drum say to you the first time you read it?

When it was published (1959) I was in France. When I came back to Germany, I was in my 20s. Guenter Grass was then politically very engaged with the social democrats. We were more Left leaning while he was always criticising the Left. So that did not make the novel attractive to me. And it had to be Franz Seitz, who produced my first film (Young Torless), who came to me in 1976 and said we had to do this film. I refused to read it ‘cause it’s not my cup of tea (laughs)’. But Seitz was smart and kept coming back. (So) I started to read the novel. When I read it the first time, I couldn’t imagine how I could ever do this film. Slowly the novel grew on me.

Today, I really love the novel. I love Guenter Grass’s writing too. For, he opened the horizon for me. I understood finally why he was a social democrat and not a leftist. He said that had always been the mistake, that’s why Hitler came to power, explaining that the extremists, the extreme Right and extreme Left, paved the way for a populist demagogue at the centre. His descriptions of the child (Oskar) and the rest are absolutely wonderful. The novel served as a key for me for many, many things.

Was there ever talk of a sequel?

Yes. For 10 or 15 years we were trying to do a sequel. We must have written 12 or 15 drafts, extending it from where the film stops in 1945. Of course, the book goes on to the late 1957-’58. But we extended it to the building of the wall and even until the fall of the wall; and little Oskar was, meanwhile, an old man. We wrote episode after episode. But the producers and distributors didn’t want to do it. They thought it was interesting, but said it was not as good as the first part. Because essentially, here, Oskar is a loser. He doesn’t have a drum and doesn’t have that voice any more (his high-pitched shrieks could shatter glass). So, Oskar becomes isn’t really much of a hero. But I would have loved to do it.

Would you do it now, if offered?

No. Because, the actor, David Bennent, who played Oskar as the boy, is too old. But we had adapted the sequel as the boy was growing up. The way he looks now, he would have been perfect for the end. But he would no longer be fit for the beginning.

But technology could have helped you create a younger version of Oskar with David as he is today. For The Irishman, Martin Scorsese has apparently managed to create youthful versions of DeNiro and Joe Pesci.

No, the time has passed for a sequel to The Tin Drum. We should have done it right then. It got too late. It’s funny how the same producer who wanted you to do it in the first place, didn’t want you to embark on a sequel.

---------------------------

In the director’s cut put together in 2010 Schlondorff added, apart from several scenes edited out of the released version that won them the honour at Cannes, newsreel footage of historic milestones. For, while writing the screenplay, it was Jean-Claude Carriere (Peter Brook’s Mahabharata) who made him aware that Oskkar is there at all the turning points in history.

“We see him at the time of the rise of the Nazis, when they take power, at the start of World War II, when the Nazis invade Poland, arrive in the city of Danzig, occupy France… And when the allies have their D-Day in Normandy, Oskar happens to be there too. And when the Red Army arrives finally in Gdansk, Oskar finally reaches there,” Schlondorff explained to the Nandan film aficionados. The idea, he added, was to introduce footage of the “transit of history” to show that the film wasn’t only about this crazy story of a three-year-old boy who refuses to grow up and does all kinds of mad things.

---------------------------

Guenter Grass at a north Calcutta mansion during his visit to the city 1985. The Telegraph file picture

You were fortunate to have been able to re-do the film.

Yes. We are now working on a 4k restoration. We were so lucky to still have all the negatives, 40 years later. They were well kept. If you were a cameraman, you would recognise the bits that were added in my director’s cut. These are better, because they are from the original negatives while the rest of the film is of course the dupe negative (a copy).

One of my favourite scenes is when the three-year-old goes under the stage, plays his drum and disrupts this German military congregation with hundreds of families of men, women and children, watching and cheering the parade.

It is brilliant in the book. I did not change a single comma. It was written as if it was a screenplay. The cuts of the children, the women, a boy on the shoulders (of his father) with a flag, and Oskar drumming away are all in the book. People often miss the fact that Guenter Grass is a very visual writer, because he always has this cascade of words; words, words and more words. He made me aware that somehow, each chapter is written around an object… Consider the horse’s head. I don’t know where it came from. It is almost like Guernica.

How did you pull off that scene, especially the way the fisherman brings out live eels from this huge, severed head of a horse that had just been pulled out of the sea?

I’ll tell you a typical socialist story. We were in Poland shooting (Gdansk), and the only difficulty we had was to get the eels. Every morning, the local prop man came back to report that there were no eels in the market. So, I spoke to our German prop man and gave him 100 DM, which was a lot of money in Poland those days, and told him to go to the harbour early morning when the fishing boats return from sea and buy the eels. Sure enough, he arrived with a bucket full of eels.

A taxidermist had prepared the head, inside which we made a box with a lid attached to a nylon string. We had also put some eels into the mouth and ears of the horse’s head and then sued them up. Please do not tell the animal activists. Once the head was on the beach, the prop man pulled the string and the lid opened and the eels came out. Otherwise, they would swim away.

It was so real. Many in the audience would have had the same reaction as Oskar’s mother did after seeing that spectacle.

Most people say, and that was right after they read the book, that they could never eat eel again. But I have eaten a lot of eel with Guenter Grass. Before we made the film, when Grass was living by the sea, we had bought eel for a meal. I remember he was cutting them on the table very much like in the movie. So, I knew exactly what to do with the eel.

The music for The Tin Drum was by the great Maurice Jarre (Lawrence of Arabia, Doctor Zhivago). You have described his qualities as a mix of “emotion”, “intelligence” and “discretion”. Explain that.

Each time I hear his music, I love him more. He never underlines what you see or feel. That’s what I mean when I say he’s discreet. He does not want to manipulate you either. That is his respect for the audience.

He will not tell you what to feel.

Exactly. But once you have a feeling, he can amplify it, which means it often comes later than expected.

So, Jarre was different from Ennio Morricone (of Spaghetti westerns fame).

Maurice had a sense of melody, more in the tradition of Bernard Herman and Max Steiner. But unlike Morricone, who had a facility to invent tunes, Maurice went out to find them. For the famous Lara’s Theme (Doctor Zhivago), he looked at all kinds of Russian folk songs and picked one. For The Tin Drum also we scoured music libraries for German folk songs, although I don’t think he found anything.

In Imaginary Homelands, Salman Rushdie articulates what Grass’s “great novel” told him: “Always try and do too much. Dispense with safety nets… And never forget that writing is as close as we get to keeping a hold on the thousand and one things _ childhood, certainties, cities, doubts, dreams instants, phrases, parents, loves _ that go on slipping, like sand, through our fingers.”

It is very beautiful. But you know they had a very difficult relationship. Rushdie was very much an admirer of Grass. Before he even wrote his first big novel (Midnight’s Children), he came to see Grass, and they spoke and all that. And then, Rushdie published Midnight’s Children, and Grass told me, “but he ripped off my book”.

(We laugh).

But Grass didn’t think it was funny at all. I was curious and I read it (Rushdie’s book) too. But I did not find anything. I thought it was an original book. It was inspired by that idea, but then, it was not such a special idea either, you know portrait of a city and all. Of course, Grass never told Rushdie that. But he was never quite at ease with it.

What was your reaction when Grass revealed his association with the Waffen-SS?

He sent me the proofs of his book (Peeling the Onion) before it was published. It didn’t shock me at all. I was much more taken by the description of his mother’s death in the book. I could hardly understand the fuss that was made about it. Because, whether it was the army or the Waffen-SS, they always pretended there was a huge difference from one and the other. And in the meantime, it has been known that the regular army had committed just as many horrors as the others. Also, these were the last months of the war when from January to April 1945 they got in kids and old men anyhow. In a sense, the only strange thing was that he had never spoken about it before. And people of his generation, not only writers but also politicians, told me that after the war there was no way Grass could speak about it. There was so much anger, and trials were on. As an artist it would have been like death (sentence). He would not get published. So he wrote book upon book dealing with that, meaning that the fact that he had not spoken up was burning him. That was his energy, that was the gas that helped his engines run. So, after he had written all his books, he comes out with it as a ‘by the way’. And he thought it would be a ‘by the way’. He wasn’t expecting it to become such a big thing.

But there have been many who felt betrayed.

I can also understand why certain people were outraged. Because of certain positions Grass had taken. For instance, he had spoken about the graveyard where regular soldiers were buried next to SS soldiers. And then when, I think, Ronald Reagan visited that cemetery he was outraged.

As a fellow artist you have a far more sympathetic understanding of the issue.

Yes. Whether he volunteered for the SS or whether they just put him there, as he said, I don’t know. I can perfectly understand a boy — he was 16-17 then, right? — volunteering to join the army as a soldier in the last battle. Nobody was really anti-Nazi those days. Yes, they were sceptical. But the young people, like in the book, all wanted to go.

---------------------------

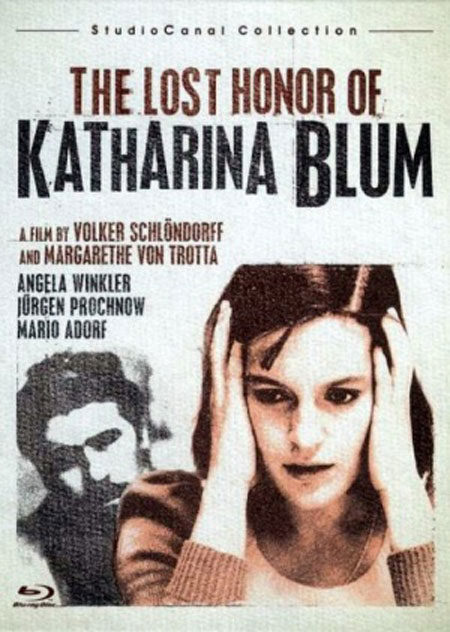

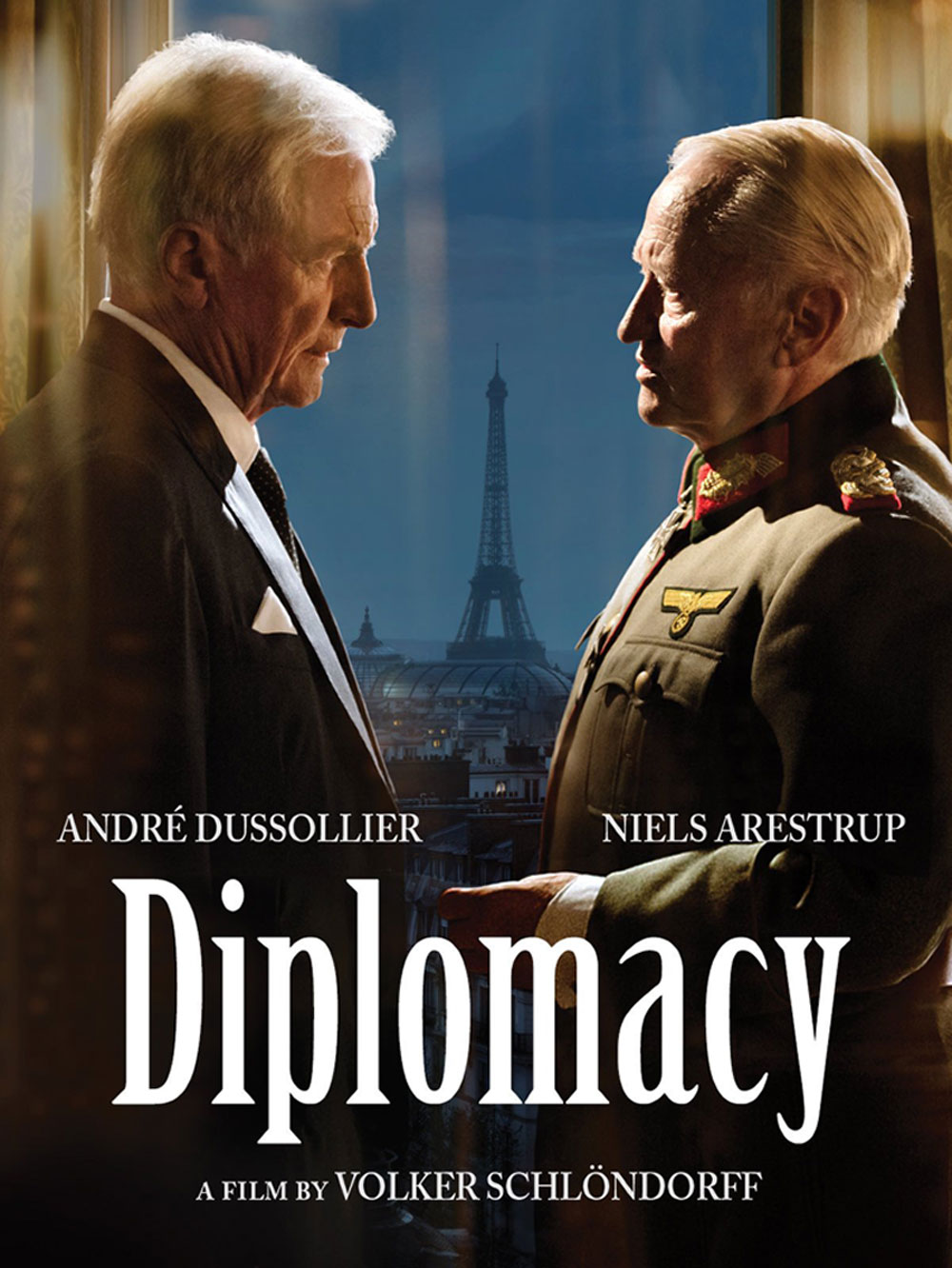

The closest Schlondorff has come to tackle human relationships is Swann in Love, based on Marcel Prousts’s novel In Search of Lost Time. Even then, he saw it more as a study in jealousy than romance. A man’s (played by Jeremy Irons) pathetic obsession with a prostitute and the near perverse delight he takes in his own suffering. Essentially though, Schlondorff is a political filmmaker, tackling a wide range of complex themes: From the class bully as a metaphor of state suppression (Young Torless) and the subjugation of women (The Lost Honor Katharina Blum, The Handmaid’s Tale) to the account of Poland’s Solidarity Movement (Strike), the story of a slow-witted French soldier who is asked to recruit children for the Nazis (The Ogre), a Swiss diplomat who convinces a Nazi general to defy Hitler and save Paris’s landmarks (Diplomacy), and of course the travails of a boy who refuses to grow up, shrieking to break glass whenever he disapproves of adult ways. Broadly, his ouvre deals with the State and its dominance over an individual’s life via institutions that are co-opted and compromised. Schlondorff calls it a “temperamental” thing over which he has had little control since his school days.

---------------------------------

Movie poster

Politics has been at the core of your work.

One group of films that I did was due to fate _ you cannot change your birthday. I was born in 1939 and, therefore, in 1955, when I was 16, I had to come to terms with this war and how it happened. Somehow, we all felt responsible for it even as 16-year-olds. About half of my films deal with German history, one way or the other.

What I may have neglected are aspects of love and relationships. …these have never been the main subject. I wouldn’t call it romantic, but Swann in Love comes very close to it. It was a study in jealousy. That, by the way, was an accident. For, it was Peter Brook’s project. He couldn’t do it because of his theatre commitments, but the film had to be shot that year. So, he asked me and I was happy to do it. I changed the cast, but I kept the screenplay which he had written with Jean Paul Carriere.

You have made films from the works of two Nobel Laureates, (Guenter Grass and Henrich Boll) and many other great writers, including Proust.

At times, I felt like a head-hunter. I have never done two films from the same writer. And I am not too proud of that.

Why do you say so?

Well, I could understand if someone does Thomas Mann all his life or, you know, focuses on one thing. But mine is so eclectic. All I can say is that there was really no plan behind it.

What about Marquez? Would you do a film of one his novels?

Oh, I would love to (now). I was even trying to at one time. I was looking at Love in the Time of Cholera. But right after The Tin Drum won Palm de’Or in Cannes, people came with A Hundred Years of Solitude. And funny enough, I said no, thinking to myself ‘no, not another of these again’. It seems I wanted to do something more surprising. I considered doing another film with Grass right away, not a novel but a new screenplay. It wasn’t so good. So that was it. But I love Marquez very much.

Marquez’s sons are planning a film of A Hundred Years of Solitude.

A yes, they would probably do it as a series.

Like you said Grass’s sons are planning to do The Tin Drum as a series too.

Of course, The Tin Drum could be done as series. But I hate series. I cannot watch it. Okay, it has a different kind of structure. I know Dostoevsky wrote in series (episodes) from one week to the next for the newspapers. But in the end it was a book. It’s like in music. It starts, builds up and there is a crescendo and then it is over. You go through the whole thing and it’s a catharsis or whatever. And it’s a major experience. But of course, no series wants to do that. No series can do that.

Doesn’t the luxury of not being constrained by time attract you? A 13-part Netflix series is like a 13-hour film.

Billy Wilder used to say a movie is like a theatre play. You sit down, the curtain goes up and after about two hours or more _ there are two intermissions, may be _ it is over. This (movie) is not an imposition or restriction. It gives me a format, like a canvass which I am to paint on. A series is more like a mural or fresco it goes on forever.

Movie poster

Looking at your catalogue of films, do you think these could be made now?

No, these films could not have been made now. The films you mentioned (seven were screened at the Kolkata International Film Festival) could not be made now. I mean they would be different films for sure. But this genre of cinema, let’s call it festival cinema, the sort of film that is not popular, but has stylistic elegance, a political conscience and a certain aesthetic is an art form. It is not popular. It seems anachronistic today. But that was my specialty, which again is an inheritance from my years in Paris where I studied and started off as assistant to Louis Malle.

Filmmakers like you, Wim Wenders and a couple of others have managed to find a middle path, straddling both worlds, so to speak, art-house festival circuit cinema and mainstream.

Yes, that’s because that was the time when there still was a middle path, at least in Europe. In the US though, screening options for European or foreign language films were very limited. But in Europe, there were no clear borders between art-house and commercial cinema. You could cross over. But there is no more of that now. Now, commercial cinema is so commercial you don’t even know whether they are movies anymore, as Martin Scorsese says.

So, you agree with Scorsese’s statement about Marvel superhero films being closer to theme parks than movies?

Well, I haven’t read his entire statement. But someone told me the gist of it. And he is absolutely right.

Finally, what are your impressions of Calcutta?

Guenter Grass had told me repeatedly to visit Calcutta. But I was a bit hesitant since I knew nothing of India, its heritage and culture. I saved a visit for the last. I was quite taken by your chief minister Mamata Banerjee. She is a fabulous speaker. The way she was conducting proceedings at the opening ceremony of the film festival was remarkable. I liked how she managed to let every guest feel at home. I will now read Show Your Tongue to understand what Grass had written about the city. I have got the book.

Thank you so much for your time. It was a pleasure.

Very nice talking to you.