My visit to Kashmir was driven by a desire to learn and understand the intricacies of Kashmiri cuisine and its influences. I wanted to find out how Kashmiri cuisine came to be what it is today. So I embarked on my culinary journey to Kashmir.

After a flight from Mumbai to Srinagar, Hashim picked me up at the airport. After a 20-minute drive, passing hundreds of uniformed army personnel, we reached the Nedous Cottage, where my first meal was the famed Rogan Josh.

Are the chillies and its imparting colour of critical importance or, is it Ratanjot alkanet, (a herb in the borage family, its notable factor is its roots that are used as a red dye) that imparts flavour and colour, or just colour? What does a saffron plant look like and what makes it the most expensive spice in the world? Why is salt added to their tea called noon chai? I already had a number of questions that I needed answers for!

DAY ONE

Famed local eatery Adhoos was a place repeatedly recommended to me and I had planned to spoil myself with all the 36 dishes that make a wazwan. After seeing the generous portions and taking the steward’s advice, I revised my orders to choose only the specialities like Tabakh Maaz, Lahabi Kebeb, Goshtaba, Haak Saag, Mirch Korma and steamed rice. For dessert, phirni, followed by the kehwa — a soothing tea consisting of saffron, gently brewed with green cardamom, cinnamon and almond flakes.

I loved the concept of Tabakh Maaz — shallow-fried boiled baby ribs with subtle but aromatic spices, ginger and mint… The Lahabi Kebab was also impressively tender and I found out that traditionally the lamb is mashed with walnut wood. Similarly, I enjoyed the Goshtaba for its satin-soft feel and bite, which paired particularly well with the light texture of the rich ghee-yoghurt sauce. The Haak Saag, a slight sour-tasting dish of greens, was great too. Quite evidently, the 10km walk back to the cottage was much needed!

On my next day, I had planned to experience Srinagar’s local streets and bylanes. I woke up feeling fresh and am certain this was due to the saffron tea.

My day started with breakfast — noon chai and girda or Kashmiri roti. After breakfast I explored the inner city with Amin, an experienced local elder. It’s always advisable to learn the culture, ways of life, traditions, weather conditions and history amongst other important influences, to understand the culinary legacy of the land. Together, we visited Hazartbal Shrine, Nigeen Lake, Jamia Masjid, Chatti Patsha Gurudwara, Hazarat Sultan Fort, Dastgeer Saheb Khaneyar and Lal Chowk. It would take me a whole book to take you through these very important places!

We also paid a visit to shops selling dried vegetables, namely ala hach (sun-dried bottle gourd), vangun hach (sun-dried eggplant) and ruangan hach (sun-dried tomatoes). These dried vegetables are rehydrated and used in locally inspired curries. We also passed by many stalls selling fried nadru chips, lotus stem fries, singara and watana.

Later in the day, I met the lady of the house, Daisy Nedous, and the insight that she shared with me can only be gained from homes who have lived the glorious past.

DAY TWO

A Kashmiri’s day wouldn’t be complete without a cup of piping hot noon chai (salty pink tea) and a crisp, freshly baked bread from the kandur — a traditional bakery. While the entire valley is still shrouded in darkness, kandur remains awake preparing the tandoor to bake breads for morning breakfast. Kandur forms an intrinsic part of the social life in Kashmir and every locality has their own kandur. In Kashmir, the kandur isn’t just a place where one goes to buy the morning and evening bread, but a social hub. It’s a place where you get to hear and participate in discussions that range from gossip to political discourses to moral lectures. It is the place where all the local happenings are discussed. The discussions that take place in a kandur shop or Kandur waan, as it is called in Kashmiri, are as varied and unique as the breads they baked.

For all the breads, aroma, smell, appearance, colour, size and overall texture are characteristics optimised by the kandurs after many years spent mastering this art. The texture and quality of these breads are determined by the percentage of wheat protein, temperature and type of flour present in the bread. There are about 14 different varieties of breads you must try when in Kashmir.

DAY THREE

The next day’s plan was something I had longed for years. We went to explore the floating vegetable market at the Dal Lake in the early hours. While on the shikara, I rode through some of the local boat vendors selling fresh produce. I was pleased to see the local Kashmiri saag, growing in full blossom — the kadam haak, turnips, lotus root and water lilies among others.

Hashim drove me to the highly sought-after saffron plantations, India’s famed saffron fields, which are a little ahead of Pampore (outskirts of Srinagar). Mesmerised by the vast acres of land being used to cultivate saffron, I couldn’t wait for my first contact with saffron growing in the fields.

Later, we left for Gulmarg and visited the Nedous Hotel dating back to 1880. I loved the feel and vibe of this place so much that I decided to stay overnight. During my stay I was told about the legendary cook Gulam Nabi, who has been cooking here for over

30-odd years now. Fascinated by his commitment, I was eager to dive in with many questions, while anxiously waiting for an opportunity to cook with him.

Gulmarg is also one of the most popular tourist spots in India. Undeniably picturesque, but for me it was still largely about learning about the food, the culture and the stories behind the traditions. I was keen to learn more about the traditional wazwan spread, which are generally portioned for four people and sharing the platter is considered respectful. The waza narrated the traditional ways of cooking and we started straightaway without losing any time. The food is served in courses as follows:

• Gosht Seekh Kebab/Tabakh Maaz (rib cage braised and pan fried under pressure)

• Lahabi Kebab (meat mashed to the texture of goshtaba but shaped flatter)

• A dry chicken, which is either roasted or shallow fried

• Methi Maaz (minced lamb intestines or lamb stomach cooked with methi, fresh fenugreek, served alongside steamed rice or a ß Kashmiri Pulao, cooked in stock with small pieces of lamb and dry fruits.

• Rista (lamb koftas or meatballs in a spiced curry)

• Rogan Josh

• Mirch Korma

• Aab Gosht (lamb cooked in milk)

• Alubhukara Maaz (lamb cooked with plums

• Waza Tsaman (paneer)

• Palak Kofta

• Waza Saag (local kadam or haak greens stirred)

• Lastly, there is goshtaba, the lamb kofta dish considered the “king of Kashmiri dishes” and the pashmina of meats. The meat is mashed continuously with a Chinar mallet and walnut wood bark to achieve an incredibly smooth paste, which is shaped into balls and poached in stock before being finished off in a mildly spiced yoghurt stew. The flavours in here are subtly enhanced using ground black cardamom, dried fennel, mint powder and a tiny bit of black peppercorns. It’s as simple as it can get but just divine in taste and best had with boiled rice.

Wazwan is most often eaten with rice, no bread. Kashmiri breads are plentiful but are associated with breakfast and tea time, not main meals. I discussed further with Waza Gulam Nabi on Pundit’s Wazawan or Hindu style of preferences such as nadru (lotus stem), dum aloo (potatoes in yoghurt), saag tsaman (paneer with local greens), rajma (stewed kidney beans with “gogji” or turnips), local river fish with nadru, lotus stem or muj, round local radish and fried fish. And then broke for lunch.

We were served some of the best dishes I have had with rice and grilled whole-wheat bread. The first was Chokha Vagun, a sour eggplant with tamarind pulp, paste of praan (local banana shallots like onion which are fried and ground into a paste), garlic, ginger, red chilli paste, green cardamom, turmeric, fennel, a bit of garam masala and bay leaf. Second was the Gosht Rogan Josh — a lamb curry with mawal, which is a local summer flower and a red colouring agent. We also enjoyed phirni.

I learnt that walnut oil used to be a medium of cooking many years ago and imparted a sweeter and nuttier flavour to dishes. I also found out that lamb has always been preferred over goat meat and considered more prime and royal, and that the meat preparation of both Rista and Goshtaba are the same. The slaughtered meat is beaten on stone blocks, or in some cases walnut wood barks, with hammers made of chinar wood until they become soft and paste-like. To incorporate air to make them light and fluffy, the meat undergoes a process of being folded while beaten. Typically, at this stage, the spices that are added are black and green cardamom and caraway.

How do we distinguish Rista and Goshtaba visually? By the colour of the sauce. Rista is primarily red due to the red chilli, while Goshtaba is whiter. Both the sauces are fine and I would like to believe that the Persian influences here have made it such. The ingredients for the Goshtaba sauce include yoghurt that is whisked with water to break its protein bonds before they are boiled in a degh (large, round-bottom vessel made of copper) to avoid splitting or food poisoning, ghee and an assortment of ground spices (cinnamon, black and green cardamom, fennel, dried ginger and coriander powder). Rista, on the other hand, uses a cooked paste of praan, garlic, red onion and the extract of red dried chilli.

For a perfect Aab Gosht, the meat is traditionally cooked with milk, or aab. Here, I am told that they reduce fresh milk with cinnamon, green cardamom, paste of praan, garlic, ginger powder and fennel powder and the tender boiled meat is simmered in the milk sauce until the flavour becomes well-rounded.

Other dishes made here include Doon — a walnut chutney particularly important in wazwan, made from milk-soaked walnuts, mint leaf, yoghurt, green chillies and salt; onion chutney prepared with yoghurt, green chillies and mint; dum aloo, fried potatoes gently cooked in a yoghurt sauce made with praan, garlic, bay leaves, green cardamom, cloves, dried ginger and dried fennel seeds, and corn bread (makai roti). Walnuts are abundant here and are frequently featured as part of the dessert menu, unlike in London.

Following a catch-up with Waza Bakshi, lovingly called “Amma Kaka”, I was able to gain more insight into the ingredients used in dishes and variations. For example, I learnt that the quince apple, locally called bamsooth, is sometimes served for a wazwan as a side dish or accompanying the meats. Most dishes are red in colour, except for the likes of Yakhani, Goshtaba, Dhaniwal Khorma, Hindi Rogan Josh (orangish) and many are finished with fried praan paste (for taste) and a pouring of hot oil on top. Relevant dishes are also further enhanced in colour by saffron extract or mawal.

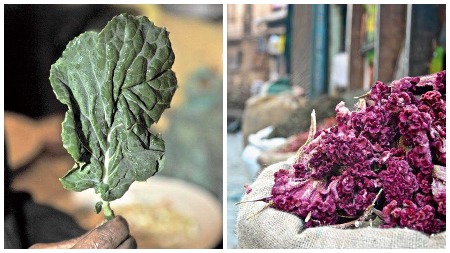

In terms of the greens I encountered, I found out that knol-khol is called kadam, and its greens are the saag which Kashmiri’s refer to as kadam saag. For Haak, these local greens are traditionally made with garlic, red whole chillies and garam masala. The texture is more like cooking spinach, but they have a profound taste. It is best enjoyed fresh and the locals would recommend spicing it up with red chilli extract. Most wazwan food is made with caramelised onion in smoked mustard oil. Another fading trend is the previously widely used earthenware and wood fire cooking methods. Likewise, is the traditional lentil preparation here in Srinagar called Dal Dabbi, using green moong lentils.

Interestingly, trout is the most commonly consumed fish along with the fish from Dal Lake. Fish is locally referred to as gard and is traditionally cooked with three vegetables — muj/ radish, haak/Kashmiri saag and nadru/lotus stem.

Did you know that tumul is the local rice used for wazwan? When cooked, its appearance is similar to sella rice. Wazwan may also feature the Kashmiri pulao. It is prepared by first dry-roasting the rice with abundant ghee and later add stock or boiling water (generally 2:1 water to rice ratio) with brown praan paste, cinnamon and green cardamom.

After a hearty conversation, noon chai (salted brewed tea) was made for all to drink. We sipped and got cracking. A few signature dishes were being prepared with Waza Bakshi for my farewell dinner — Alubhukara Khorma, lamb and sour plum curry, Gard Tey Muj, Khaneyari Haak, fish with radish, lotus stem and local greens!

It was Bakra-Id the following day and post attending their ceremonies, I left for the airport to get back to Mumbai. I had been looking forward to this experience of Kashmiri wazwan cooking for so many years and it was as insightful and fulfilling as I had hoped.

The author on a shikara on the Dal Lake in Srinagar

Readying meat for Goshtaba

Cooking Tabakh Maaz

Fresh girda

The author being shared knowledge with by the local fisherwomen

Haak greens (left) and mawal, the red colouring flower used for Rogan Josh

Lotus stem (left) is a common ingredient as are red Kashmiri chillies

Saffron flowers that yield this unique ingredient in full bloom

The author at the saffron fields in Pampore

Chef Jolly, aka Surjan Singh, is a TV personality, culinary consultant and currently the corporate culinary director and business development head at Speciality Hospitality UK Ltd