After his 8pm dinner, Father John Leonard Moore (1918-1988) would go for a long walk. Every evening, the Jesuit priest and educator from Australia used to pass by the home of Amitava Bose (Kanti), who was part of the administration of the Bokaro Steel Project (later Limited). Father Moore had established St. Xavier’s School in Hazaribag, Jharkhand (then in Bihar), in 1952. Thereafter, the administration of the Bokaro Steel Project approached the Jesuits in Hazaribag to open another school in the township in the mid-1960s. Father Moore, who had returned after “resting” in Australia, was called upon to establish it.

Father Moore would drop by whenever necessary to meet the workaholic Bose who returned home late. One evening in 1971, the priest knocked twice but Bose wasn’t home. When Bose went to meet him at the staff quarters, Father Moore asked him to admit his daughter, Tutul, to the school. When Bose said the four-year-old (born 1966, the same year as the Bokaro school) did not know her English alphabet yet, Father Moore exclaimed: “That is not your business. What are we here for?”

Soon, father and daughter met the priest again, and both wished him “Good evening”. Father Moore was delighted to hear the child warble in English and got Tutul admitted to Preparatory in Xavier’s, probably the first co-education St. Xavier’s School anywhere.

Former students of both Hazaribag and Bokaro Xavier’s — from the 1950s to the 1980s — have similar anecdotes to relate that shed light on this visionary’s philosophy of “education with a human face”.

Sujit Sen (born 1951) of the class of 1967 and a chartered accountant by profession, fondly recalls how the priest had practically forced his father, a refugee from East Bengal with a huge family to feed, to get all his three sons admitted to Hazaribag Xavier’s, never mind that he could not afford their fees right then. “His was a great entrepreneurial achievement. It is unbelievable that within a span of 26 years (1952-88), Father Moore established two worldclass schools. He should be a case study in management schools,” says Sen.

Rohinton Kapadia (1943-2015), professor and head of the department of English, St. Xavier’s College, Calcutta, “was fortunate to be one of a team of pioneers starting a new school (Bokaro)”. He wrote that Father Moore “believed that good human relationships were vital in education”.

As a tribute to the man who touched so many lives, the Jesuit Provincialate, Hazaribag, is publishing a book.

John Moore grew up along with his 11 siblings on a farm at Yarram in Australia’s southeastern corner. Like them, he was sent off to boarding school conducted by Jesuits in distant Melbourne. In 1932, he moved to Xavier College, and in his final year he “warmed to the idea of himself becoming a Jesuit”. He entered the Jesuit Novitiate in Watsonia in 1936. During his training, he distinguished himself as an educator as his charges felt he could instinctively understand them. So Father Moore was among the six Australian priests who set sail for India in February 1951.

In September 1951, when he was studying Hindi in Ranchi — in Jharkhand then Bihar — Father Moore was ordered to open a boarding school in unfamiliar Hazaribag. Brother Nicolai Bilic (1890-1968), master of carpentry and house building, constructed the structure that served as the hostel. Sure enough, the school opened on January 28 with 22 boarders and 15 day scholars.

Disciplinarian though he was, he wanted the school to be a living “community of happy boys”. He believed in flexibility, and he felt that the “curriculum must be adapted to the needs and rights of each student”. The boys called him “the Boss” behind his back, but his “door was always open for them” — for “delinquents” as well.

Anjan Sinha (born 1952), who passed out from Hazaribag Xavier’s in 1968, and who began teaching at Bokaro from 1974 till his retirement in 2012, says Father Moore had taken the initiative to start a small Hindi medium school for underprivileged children. He encouraged the English medium school students to teach them. Initially, students used to sit under trees when classrooms were unavailable. The students guided by teachers launched an organisation named Social Service League and a good number of them volunteered their services. “I was there after I joined as a teacher, and students who had passed out were always trying to help out others. That was the hallmark of this school. Initially, it was free but as it grew and teachers had to be appointed, a nominal fee was charged,” says Sinha.

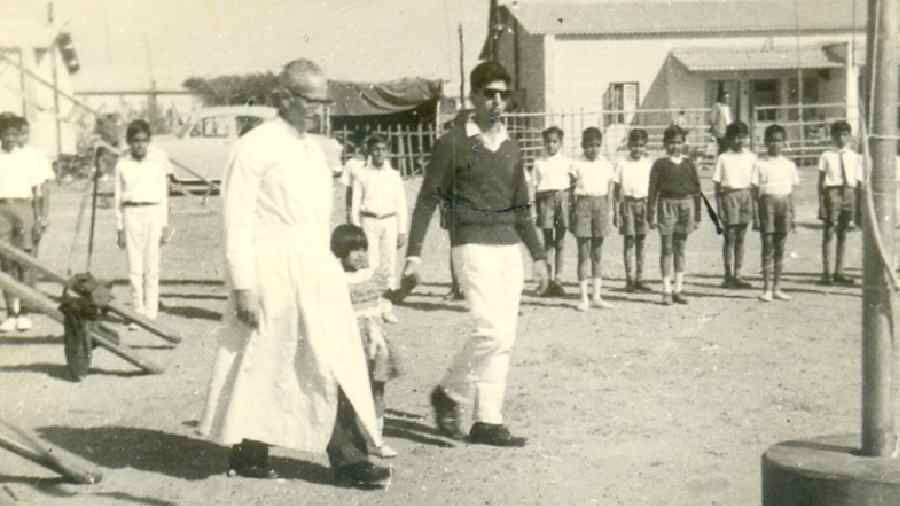

Sinha recalls how the outdoorsy Australian priests motivated the Hazaribag boys to participate in games and athletics. The time meant for sports was restricted in Bokaro because it was a day school and both boys and girls had to be accommodated. Students were allowed “the largest measure possible of personal freedom limited minimally by a system of restrictive external discipline”.

In Father Moore’s moral universe, Christ was the “model for the commitment of the spiritual person”. Yet the coexistence of various faiths could “greatly enrich one another in their ways of perceiving and expressing the divine spirit in them and the community”. An object lesson in peaceful coexistence for India as it is today.