My childhood lives in a steel township in erstwhile Bihar. A time when our family comprised the parents, my paternal grandmother whom I called Thama and Thama’s pink book that was the panjika. And then, as now, the omnipresence of the panji made our house different from those of my friends.

I can still see Thama, a bundle of white cloth — she was small and stout and would sit with her feet tucked sideways underneath her — holding the pink book in her rounded fair hands, bare except for a pair of gold bangles.

As a child I found incongruous Thama’s acceptance of the vile pink panjika. She had been widowed when she was in her early 30s and had since worn only white saris with a narrow black border. Reds, pinks, oranges, maroons had no place in her life and certainly not on her person.

The panjika was Thama’s oft-read book. She consulted it throughout the year — for Satyanarayan puja, for ekadashi when Hindu widows observe a ritual fast, for ambubachi and umpteen rituals and fasts.

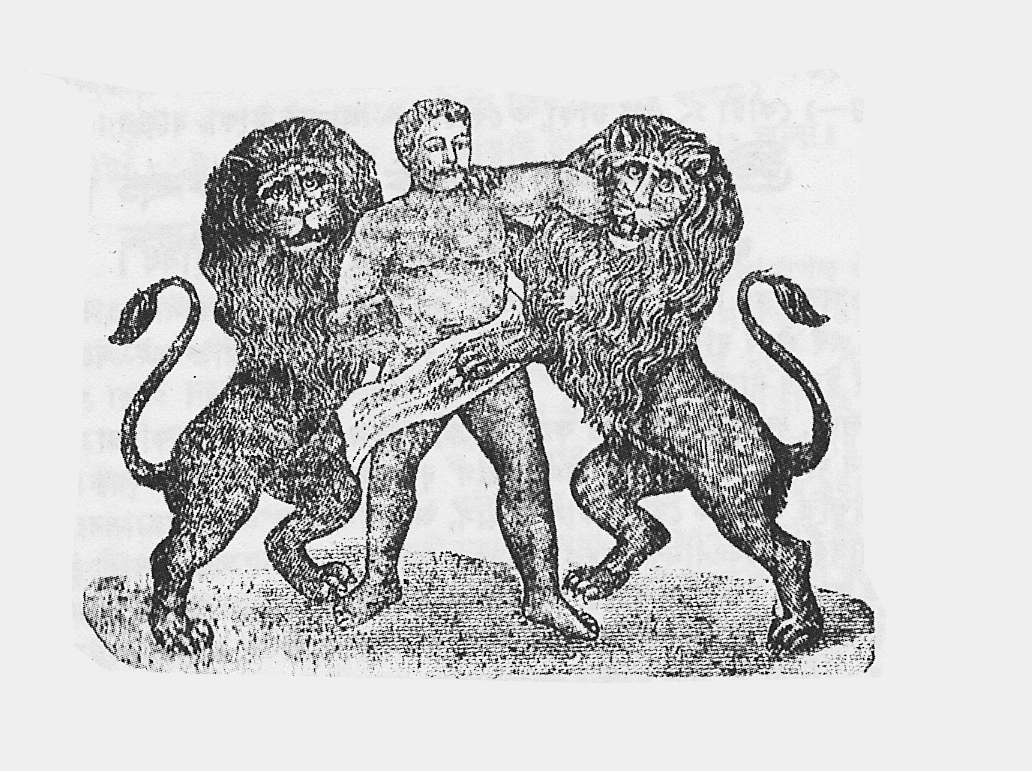

In the Bokaro of 1970s, Bengali was widely spoken but schools didn’t require us to learn the language. Though the contents of the panjika were as Greek or Latin to me, the child’s eye was quick to spot the colouring opportunity. The book contained innumerable black-and-white sketches of gods, goddesses, demons and humans, birds, animals and flowers too. Some afternoons when sleep eluded me — but not the others — I would sneak into the puja room, where the panjika was kept, and turned the pages. I never had the courage, though, to add colours to what I knew to be rightfully Thama’s and Thama’s alone.

Looking back, I figure that at some point she must have got a whiff of my secret dalliances because the almanac quietly moved to a rack in her room.

Not that it deterred me. By the time I was in high school, I had learnt to read Bengali. I would, whenever possible, dip into the panjika and devour the daily predictions, the annual predictions. But as I couldn’t remember the Bangla months in their correct order, much to my mother’s chagrin, it was somewhat of a challenge.

Around this time I realised that not all Bengali households in Bokaro owned a panjika. It was mostly families with an elderly member or two that were in possession of this quaint item. Having said that, it was not as if the rest didn’t fall back on it. They did not buy it, but they sure rang for it.

Death anniversary. Some puja. Someone getting married. Someone’s thread ceremony. The big fat black telephone at our home would ring away with polite panjika queries. Thama and my mother always obliged.

Thama has long taken leave of the mortal world but the household ritual of buying the pink book come every Bengali New Year continues. After my father’s death, the onus of procuring a copy fell on me.

But what was this? When I got my panjika purchase home there was considerable fireworks. I learnt that not all pink panjikas are considered kosher, not in the family home. The one I had got was from Gupta Press, while we had a tradition of consulting Benimadhab Sil’s Full Panjika. Needless to say I never forgot again. Sil was sealed in my head.

In the new panjika, many gods have acquired gloss and colour. Advertisements of astrologers and self-proclaimed godmen have crept in. Among new chant additions are the Sri Sri Lokenath Babar Panchali, Saibabar Bratakatha and Sri Hanuman Chalisa. “Holei holo, badha kisher… Everything is possible today, who’s stopping anyone,” said my mother stoically.

I have developed my own little use of the panjika. Every six months I whisk it out and check the auspicious marriage dates. “Because you need to buy wedding gifts,” asked a colleague when I declared as much. “Because you look forward to the lunches and dinners,” asked another. “Because...,” started yet another.

No, no and don’t even try. I consult the panji so I have an idea of the dates on which my electrician will be relatively free to clean my ceiling fans. Weddings, after all, need a lot of lighting, consuming much of his time.