The best way to identify a “terrorist” in a Bollywood film is by his kohl-lined eyes. The latest example is The Kashmir Files and we will not delve into the viciousness of the rest of the film here. But a man’s kohl eyes are by themselves a phenomenon worth looking at. They are backed by a long line of tradition in popular Indian cinema which has been reinforced recently.

Strictly speaking, a man wearing kohl, or surma, may be more than a “terrorist”. On screen, a man’s kohl-lined eyes signal a whole spectrum of “moral ambiguity” and “deviance”, from being a “terrorist” to being on the other side of the law to non-masculinity to just being Muslim, the last often being crime enough in contemporary India.

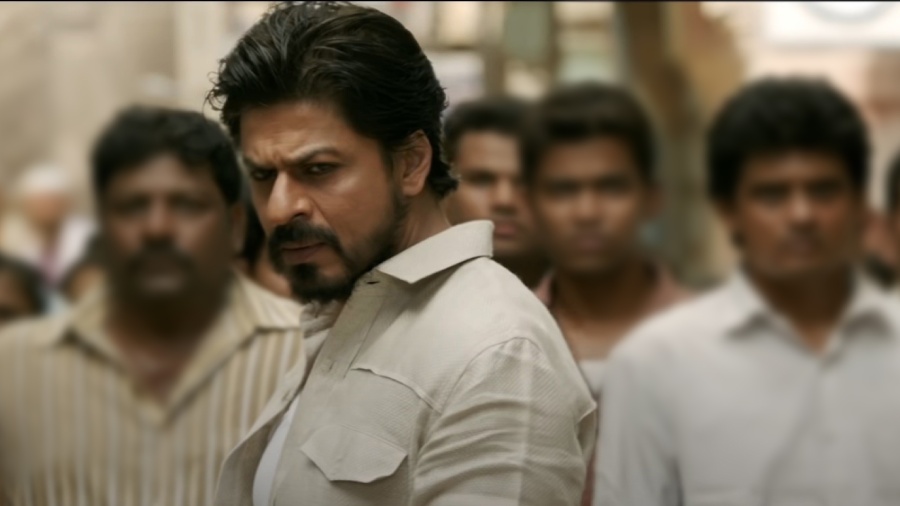

Notable Muslim aggressors have been sporting kohl of late. In Padmaavat (2018), Ranveer Singh as Alauddin Khilji is a psychopath-entertainer, laughing over an orgy of blood, even as his full-on smokey eyes burn like hellfire. In Kalank (2019), Varun Dhawan has kohl-lined eyes and is a womanising blacksmith who has designs on the lovely lass of class in period chic played by Alia Bhatt. Dhawan’s character is called Zafar Chaudhry, a reference to his illegitimate, imperfectly-Hindu origin, but all the other Chaudhrys have totally legitimate Hindu first names. However, perhaps because he is part-Chaudhry, Zafar redeems himself. But no such luck for Abdul Khan, the man who is consumed with communal hatred, and, you guessed it right, his eyes are lined with kohl. In Raees (2017), Shah Rukh Khan is a bootlegger king in full Pathan costume and surma eyes.

The kohl could have been appreciated as a nice touch, as some Muslim men do line their eyes (other men from other communities do that too, we forget), but then why does an alarm go off in our heads the moment a Muslim man comes on screen with bold kohl eyes? It is because as an audience we have already been trained to spot the “terrorist”.

Only a few years after the separatist movement started in Kashmir in the Eighties the “Muslim terrorist”, the villain who is destroying the idea of the nation, began to emerge as a demon on screen. The identifiers were his clothes, the language he spoke and the thick surma. Mani Ratnam’s Roja (1992) is a landmark Indian film. Among other things, it helped to establish the stereotype of the Muslim “terrorist”, which means anyone who wants an independent Kashmir. Film scholar Ira Bhaskar calls Roja a “nation-in-peril film” in which Kashmir is perceived as a paradise under threat, “is wounded and bleeding”, and “the people who are destroying it are depicted as cross-border terrorists”. You are asked not to look further into history.

As “good Muslims” are distinguished from “bad Muslims”, “good terrorists” can be told from the “bad terrorists”, the film says, using kohl. Is it a coincidence that Pankaj Kapoor as Liaqat, the “terrorist” who converts to the idea of India, does not wear kohl, but kingpin Wasim Khan does, and in the prison scene he strongly reminds one of Hannibal the Cannibal from The Silence of the Lambs, a film made a year before Roja. The “good Muslim” can be assimilated into the fabric of the nation, and no eye make-up will make it happen faster.

Vidhu Vinod Chopra’s Mission Kashmir (2000) reaffirms the colour code. The dreaded terrorist Hilal, played by Jackie Shroff, lines his eyes with thick kohl, raises them in slow motion and looks seriously sexy, reminding us of the sensuous appeal darkened eyes can have in both men and women. But Sanjay Dutt’s character, a “good Muslim” because he is an army man, has squeaky clean eyes. In Sarfarosh (1999), another film on terrorism, the villain wears kohl.

The frequency of kohl in men’s eyes increases in Hindi films as the conflict intensifies in Kashmir and Hindutva continues its violent march across the country. By the time we come to Agneepath (2012), Rishi Kapoor plays Rauf Lala, a trafficker of young girls and a drug lord, another monster with burning kohl eyes. Earlier in Veer Zara (2004), Manoj Bajpai’s character, a Pakistani Muslim, had lined eyes that hinted at menace.

Not that Bollywood was entirely innocent ever. In Noorie (1979), otherwise a gentle, lyrical film set in Kashmir, Farooq Sheikh, who plays Noorie’s lover, has clear eyes, but the man who rapes Noorie has painted eyes.

Even when a “good Muslim” wears surma, it says something. He is orthodox, it is implied. Pran’s character in Zanjeer (1973), who lined his eyes famously, was not on good terms with the law to begin with. A society has to mark the offending Other with something, and kohl is very handy that way, literally. For Muslim women, hijab serves the same purpose and Hindutva’s propagandists forget that the ghunghat, or the ghomta, is such a big Hindu institution in some places still, though this is not an argument to justify either the hijab or the ghunghat.

Before the advent of “terrorism”, Hindi films used surma to mark its Hindu characters as well. Sunil Dutt in Reshma Aur Shera (1971) wore eyeliner, giving competition to the beauteous Waheeda Rahman. His character was not on good terms with the law either.

Kohl in a woman’s eyes, however, is almost universally accepted as an aesthetic practice, rendering it into a feminine thing, perhaps another reason kohl in a man’s eyes can be seen as suspect in many masculinist cultures. Though Los Angeles now is full of men sporting the “guyliner”, traditionally Hollywood has looked askance at men with lined eyes, or has lined the eyes of men it looks askance at. Or fears.

Charlie Chaplin’s tramp had lined eyes, as did some of the greatest evil on screen: Alex Delarge in A Clockwork Orange (1971), Voldemort, Heath Ledger as Joker (he has the maximum black), and even Scar, the evil lion, in The Lion King (1994).

One wonders how this came to Hollywood. Was it historically transmitted from the time fair “Occident” discovered dark “Orient” and as the fears and the hostilities were nurtured through the Crusades and the wars of the subsequent centuries, the “Oriental” man, the “Saracen”, remained marked the exotic Other, and more often than not, evil, with the kohl in his eyes? Western culture has never really encouraged men to use colours on their faces, except in brief spells, such as under Queen Elizabeth I.

The power of association is strong. During the Crusades the word “assassin” is said to have come into English from the Arabic hashshashin, derived from hashish, said to be used by those who were going into battle. A similar leap of imagination could turn the “Oriental”, who wore kohl, into the Enemy.

Such things persist. But it is interesting that India, too, where the male Hindu gods are often depicted with lined eyes, shows a similar strain of Islamophobia. What if Hindu men were serially portrayed as aggressors — there is enough evidence of such violence — marked with the tilak?