Was it your idea to make a film on Mujibur Rahman?

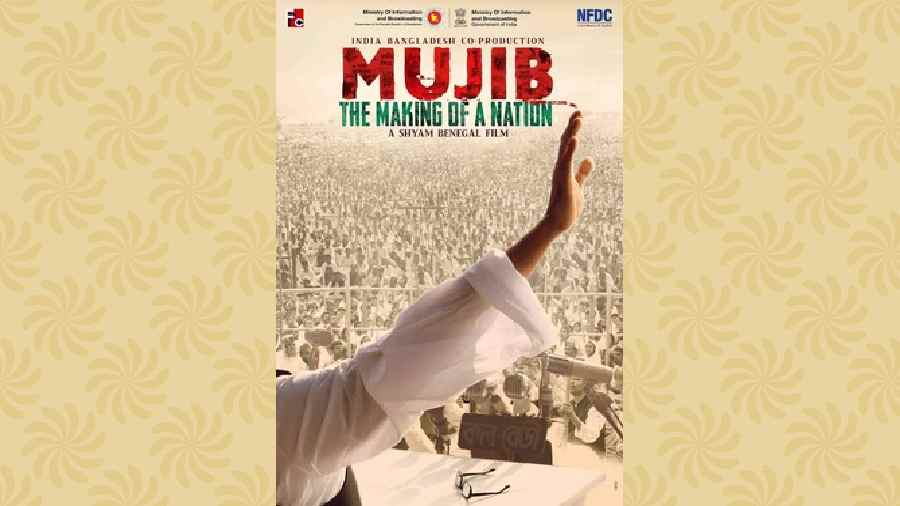

No. It was an opportunity I fortunately got. When you are a professional filmmaker, there are opportunities that are missed, opportunities that you lose. In this case, when I got the opportunity, I grabbed it. I had started reading about Sheikh Mujib earlier. He was fascinating. He was a true patriot. He was also very passionate about what he was doing. He has been quoted somewhere as saying, “My strength is that I love my country and my weakness is that I love it too much.” I found this quote very telling and started studying more about him. So when the project came to me under the co-production treaty between Bangladesh and India, it was like a gift. Also, the Government of Bangladesh was quite happy to have me as the director of the film.

And the film is in Bengali?

Yes, and it is a language that I do not know. But there is a reason behind this. The Prime Minister of Bangladesh, Sheikh Hasina, wanted me to make it either in English or Urdu or Hindustani. But we eliminated the idea of making it in Urdu or Hindustani for the simple reason that Sheikh Mujib was a Bengali nationalist. The battle was fought because Pakistan was trying to force Urdu as the national language when the majority of people in East Pakistan were Bengali. He was a Bengali nationalist. It was an essential part of his life, of himself and his people. A sequence in the film shows Jinnah addressing students in Dhaka University where Mujib was a student. His speech as recorded quoted him as saying that Urdu would be the language of the nation. When the students protested, he shouted, saying they must remember he had a vision for Pakistan that he would fulfil come what may. Mujib’s political life began from there, so it made sense to make the film in Bengali. For its distribution outside Bangladesh, we will have subtitles or it could be dubbed in English or Urdu or whatever language is required.

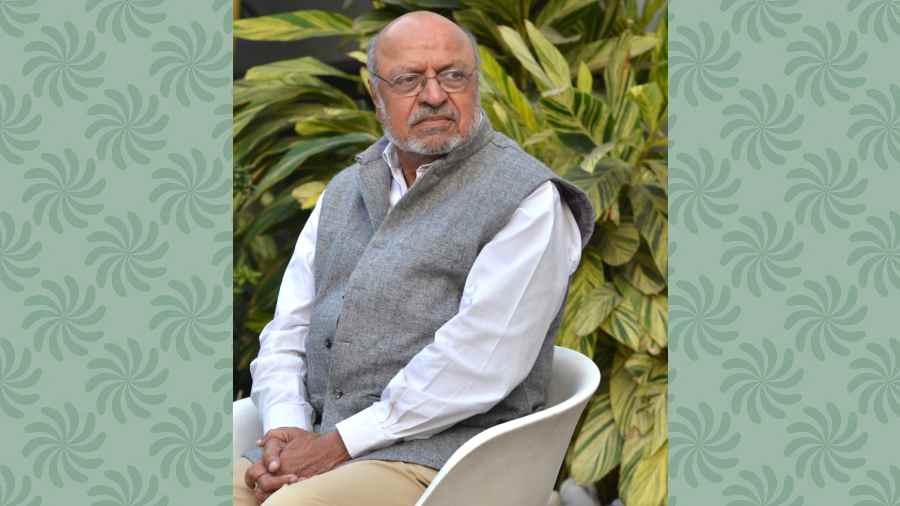

Shyam Benegal

As a person who does not speak Bengali, was it difficult?

I had excellent support from the writers, from Bangladesh; the interpreters translated with great precision.

These days there is a controversy about everything. Recently, The Kashmir Files was released and there is continuing controversy over it. And here you have made a film on the founding father of another nation.

It is a huge responsibility. There were some people who were critical saying why should an Indian make the film when there are excellent Bangladeshi directors. The fact is, this is a co-production between two countries — Bangladesh and India. A number of directors were suggested by the Bangladesh Film Development Corporation and the National Film Development Corporation of India. Finally, I was asked.

And it is an all-Bangladeshi cast?

Yes. Entirely. I had the choice of using Indian actors. But I felt it made no sense to do that. Suppose I want to make a film on Gandhi or Nehru, would I use actors from any other nation?

Mujibur Rahman is not an easy subject to capture. He was a complex person.

(Interjects with a laugh) Of course, he is a very complex person. But politicians are complex people.

So your portraiture is…

This is a biographical film but you see Mujib from a very intimate point of view — his wife’s. It is the way Renu knew him. The story is actually being told by her, in her voice and how she sees her husband. That is the optic I wanted. She was taken to his home when she was a little girl. She grew up in that household and then got married to Sheikh Mujib. So it was a very good point of view to have. She was the closest person to him. He was closest to her. There is a political Mujib, there is a social Mujib, and there is a Mujib, the family man. All these make up his persona.

You have made a film on Mahatma Gandhi and also on Subhas Chandra Bose.

(Laughs): And also on Nehru.

You made Bharat Ek Khoj based on Nehru’s Discovery of India all those years ago for TV. What I meant to ask is, when you shot this film on Mujib, another political icon, was it different in any way?

It can never be the same. It is not something being produced from an assembly line (laughs). Each of these individuals is different. Different and extraordinary. It is fascinating to make biographical films because you get to know a person and how he or she functions. You see their weaknesses, their strengths, their passions, all of that.

If you talk a bit about all the background work...

The film is not only about Mujib, it is about the different phases that Bangladesh has gone through, as a part of undivided India, as part of Pakistan and a free nation after seceding from Pakistan. I went to Bangladesh several times. My writers went too; they did long interviews with everybody who matters in Bangladesh and also with people who were involved in the freedom struggle. The people in Bangladesh were very forthcoming. The PM herself was very helpful. She gave much time to the writers and explained many details. My daughter, the costume designer, also met her and came back with many insights.

You made your first documentary when you were in your twenties. You have made Mujib at 87. How has it been different?

Actually, I made my first film when I was 12 (laughs heartily and pauses). Later, I made an anthropological documentary about the Muria and Maria tribes of Bastar, and then in 1967, I made a documentary on the nationwide strike by students.

As you age two things happen. There is the experience that comes with age, which is useful. Second, you think you know most of the answers. You have to fight to disabuse yourself of this notion. The process of learning cannot stop. You have to keep learning. Actually it is a mental thing. When you keep learning, your mind remains young. You’re able to learn and re-learn. It prevents you from becoming cynical.