Here are some facts. In 2017, India’s position in the gender gap index of the World Economic Forum (WEF) fell by as much as 21 points, putting us well behind countries like Bangladesh and China. According to the WEF, this alarming fall was primarily because of a further worsening of our already poor performance in the key areas of participation of women in the economy, and the low wages given to them. The highly inadequate representation of women in apex decision-making bodies like legislatures, senior management positions, bureaucracy, and professional and technical sectors has seen little improvement. In the area of wages paid for the same number of hours put, the inequality is stark. In fact, the WEF said that in our country, 66 per cent of women’s work is unpaid, compared to only 12 per cent for men.

Women in our country were also near the bottom of the heap (144 countries surveyed) in sectors like health, education, treatment at workplace and political representation. We were at position 137 in the index of opportunity for economic participation; shockingly, on the index of survival rate, we were at a low of 141! Such an appalling gender gap will take a hundred years to bridge, said the WEF report.

Our male-dominated political class does not want, it would seem, women to be adequately represented in the highest institutions of the world’s largest democracy. In fact, the Women’s Reservation Bill, that proposed to amend the Constitution of India to reserve 33 per cent of seats in the Lok Sabha and in all the state Assemblies for women, is a lapsed bill of the Parliament of India. The Rajya Sabha passed the bill as far back as March 2010. The Lok Sabha did not give its concurrence. The bill lapsed after the dissolution of the 15th Lok Sabha in 2014, and has since, in spite of occasional statements of good intentions, not been revived.

The incidents of physical violence against women continue to proliferate. The statistical bulge can only partly be explained away by the argument that more cases are being reported now. Certainly, there has to be something seriously wrong if a respected NGO such as CRY states that in India a sexual offence against a girl child takes place every 15 minutes, and that there has been a five-fold increase in crimes against minors in the last 10 years. Rape, according to the National Crime Bureau, is the fourth most common crime against women in India. Dowry, although banned since 1961, is still a pervasive evil, and a major contributor to observed violence against women. The repulsive practice of female foeticide continues to be widely prevalent. According to the Decennial Indian Census of 2011, there are 108.9 men to 100 women, strongly suggesting that whatever the laws may be, girls are being killed in the womb.

Not everything is negative. There is a new assertion in women, particularly in those who are economically independent. More girls are being sent to school, and at the tertiary level, the gap between boys and girls has considerably narrowed. We have women at the helm of many national-level institutions, both in government and in the corporate sector. We have had in Indira Gandhi a powerful prime minister, and in Pratibha Devi Singh Patil a president. The Speaker of the Lok Sabha is a woman, the raksha mantri is a woman, we have women in the Supreme Court, women who fly airplanes, and are doing an excellent job in such hitherto unlikely sectors like the police and the armed forces. Moreover, there are some very welcome institutional measures, like one-third reservation for women at the grassroots panchayat level, and in some states, such as Bihar, even in government jobs. The nationwide Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao campaign has also had some impact in giving women their due.

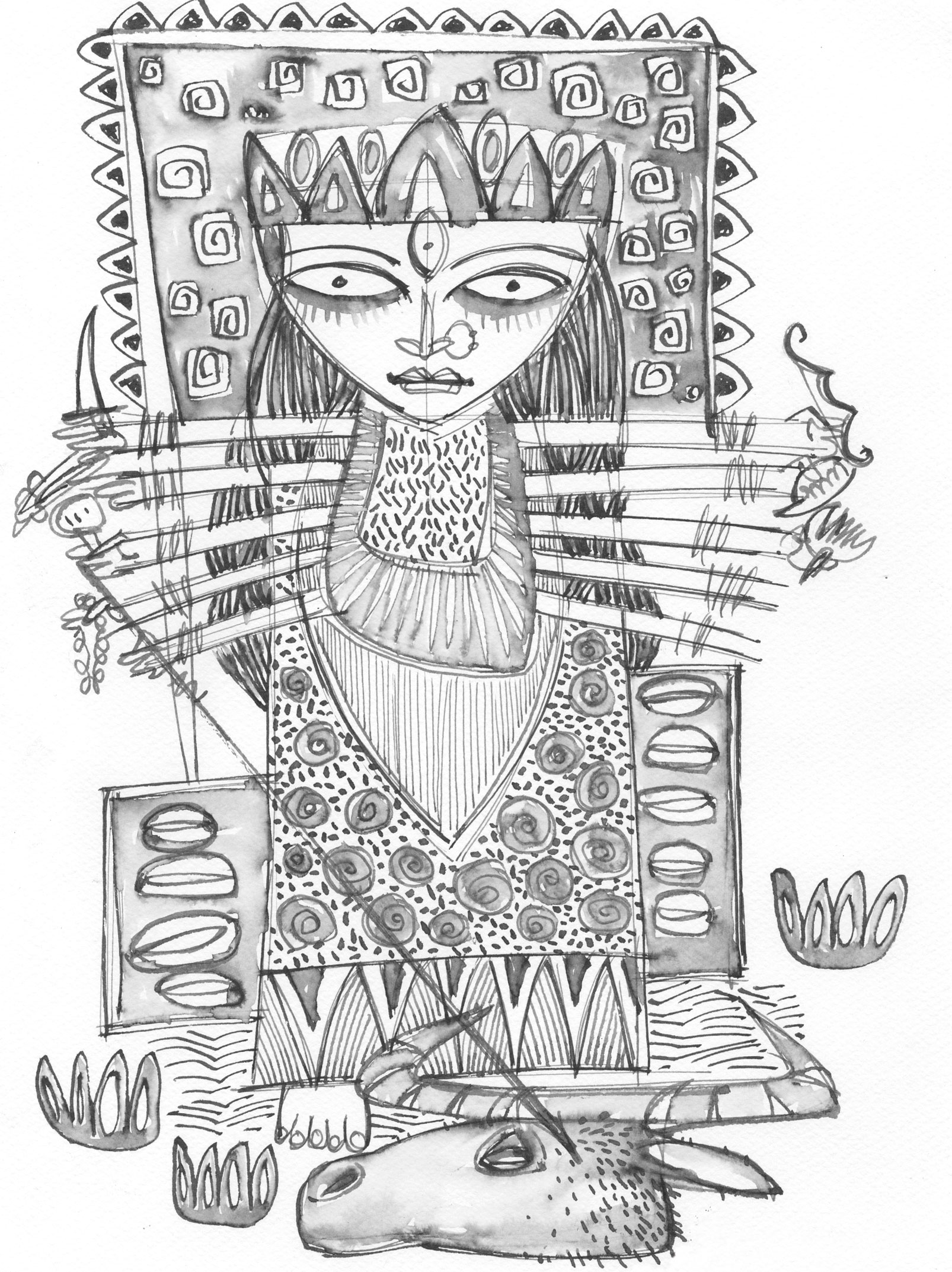

So, is Durga today ascendant or still a prisoner of a primeval, medieval, patriarchal mindset that sees no contradiction in worshipping a goddess, but oppressing the species that best represents the remarkable powers she is endowed with? I would think that this question requires serious introspection. The demon, Mahishasura, represents today the forces that oppress women. Durga today must be his nemesis.

In the festive period, let us pray that the goddess who strides a lion will soon slay the Mahishasura of hypocrisy, double standards, prejudice, discrimination and violence men and society inflict on what they mistakenly think is the weaker species. Durga, the Creator and the Supreme Power ruling our lives, is today waiting to strike.

Diplomat-politician-writer Pavan K. arma’s latest book is Adi Shankaracharya: Hinduism’s Greatest Thinker

The Durga Saptashati (400-600 CE) is unhesitatingly emphatic. Durga, manifestation of Parvati, wife of Shiva, is the Supreme Being and Creator of the Universe. Shiva, without her, is inert. He is the omnipresent, omniscient, all-knowing representation of Brahman, the attributeless (nirguna) undifferentiated consciousness (nirvishesh chinmatram) pulsating through the cosmos — unseen (adrishta), beyond thought (achintya) and indivisible (akhanda). But without the latent Shakti in Brahman, he is powerless.

Durga is that invincible, unassailable Shakti that enables Shiva to manifest himself. In this sense, she is at par with Shiva.

In Hindu philosophy, Shiva is Brahman — the unmoving, changeless potentiality — and Shakti is the power latent within him. The analogy of one that is still in perfection and the other that can ruffle that stillness, as part of an integrated cosmic design, is the essence of the Shiva-Shakti construct.

If Shiva is the still waters of the cosmic pool, Shakti is the ripple that emanates from it. In this sense, Durga, as the very manifestation of Shakti, is Adi Parashakti — the female power that has existed forever, and without which the world could not have been.

Mythology has given to this fundamental philosophical construct an even more powerful profile. If philosophy — by its very nature — is less dramatic in its presentation, mythology has no such inhibitions. The mythological Durga is not a quiet, reticent, withdrawn, passive or elusive deity. As the Supreme Creator, she is depicted as the Warrior Goddess, riding a lion, with eight or 18 arms, each carrying a weapon to defeat the designs of evil and ensure the victory of good. In this goal, she succeeds where all the gods fail. None can defeat the mighty demon, Mahishasura, who has the boon to change his shape into any form, and is waging a relentless war against the Devas. Unable to defeat him, the gods approach Durga. The Devi — whose very name, Durga, literally means “fortress”, and who is impregnably beyond defeat — then takes on the task. Riding her lion, she slays him, unwavering in her resolve, and unbeatable in her martial powers. She is willing to forgive those who are ready to change their ways, but unyielding to those who are not worthy of her mercy. That is why she is also called Mahishasuramardini, the goddess who defeats the demon, her face calm and serene as she ruthlessly meets out vengeance to the unrighteous.

If this elevated position is accorded to Durga in philosophy and mythology, what is her position today in the living world of which you and I are a part? Her persona represents the power of the female principle, Stree Shakti. Do Hindus — and Indians on the whole — accord to the female sex, as a consequence of the pinnacle on which they place the goddess, at least a fraction of the reverence they reserve for her? Is there some correlation between the deification of the Devi, on the one part, and the respect for women in society, on the other? Or, are we a nation of schizophrenics who will prostrate before a goddess, but see no contradiction in mistreating females in human form, who, theoretically, are representatives of the Devi herself?

The answers to these questions cannot be evaded. To refuse to answer them would be to accept that philosophical belief and religious ritual have nothing to do with actual behaviour. It would be to confess that there need not be a nexus between theory and practice. Durga as goddess can rule the world, with people bowing low in obeisance to her, but the Devi in human form is met with men — and often, surprisingly, women — who self-righteously stand erect in opposing her interests.

As we commence yet another year of joyous festivities to celebrate Durga Puja, let us pause for a moment to honestly examine how big the gulf is between our glorification of the female principle at the level of religion and the dereliction of our duties towards females at the level of society. Is there a meeting point between Durga, the goddess, and Durga, the women next door? Or, are they poles apart, one deservedly on a pedestal, and the other at the lowest rung of the societal ladder?