Eighty-five years ago, in the month of May, four vehicles of the Czech marque Škoda, set out on a journey from an automobile club in Prague to Calcutta in India. “It was on May 25, 1934, to be precise,” a company spokesman tells The Telegraph.

The expedition was led by Zbislav “Mik” Peters, a lawyer and a popular Czech ice hockey player who belonged to the wider family of the then CEO of Škoda, Karel Loevenstein. There were seven participants, including Peters, driving the four Populars (the name for the small family car manufactured between 1933 and 1946). There was Zdenek Pohl who drove Škoda cars in the Monte Carlo Rally of 1936 and 1937; university students František Holoubek and Jaroslav Sachl; “former nobleman” Jan Nádherný; and Jaroslav Hoffmann, a doctor of medicine. (Hoffman did not ultimately make it to India having left the expedition at an earlier stage.) Among the four cars in the expedition, there was only one Popular with a Moravian licence plate (the Czech Republic, formerly Czechoslovakia, consists of Czech, Moravia and Silesia). It was owned and driven by yet another university student, Lubomír Šebela.

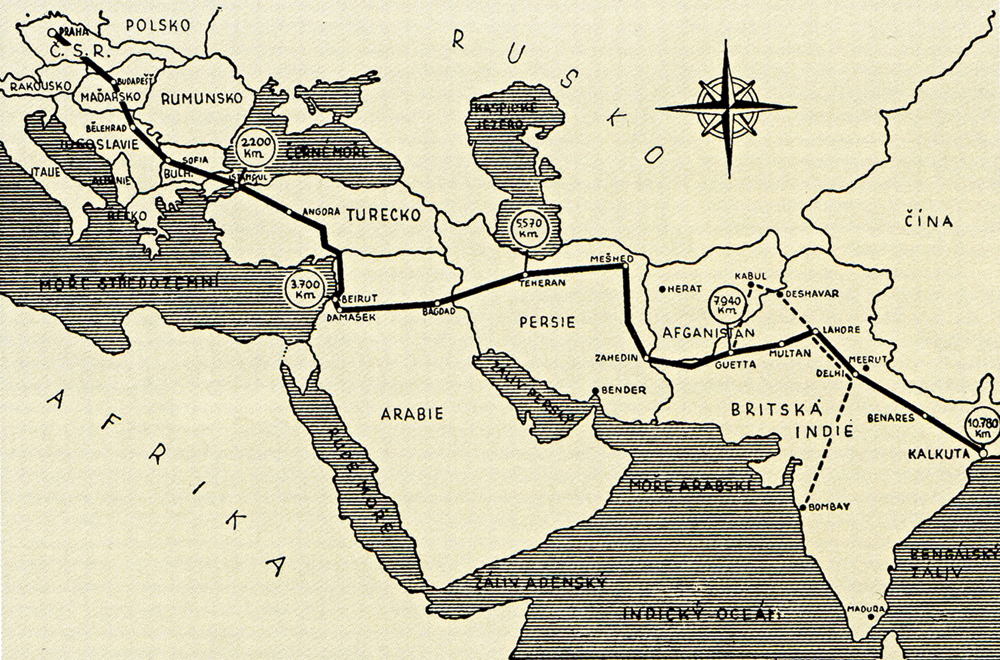

All seven of them embarked on a journey to India via the Balkans, Turkey, today’s Syria and Iraq. Šebela and his co-driver, Jan Nádherný, even made a detour via Afghanistan. Some 15,000 kilometres and four months later, the four weather-beaten Populars whooshed back into Lützovova Street (known as Opletalova Street now).

Today, none of the seven adventurers is alive to tell the tale, but bits of their expedition come alive through old pictures, hand-drawn maps, documents and a translation of a Czech-language presentation by Šebela. All of these have been made available by Škoda.

The cars in Calcutta in 1934 Photograph courtesy Škoda

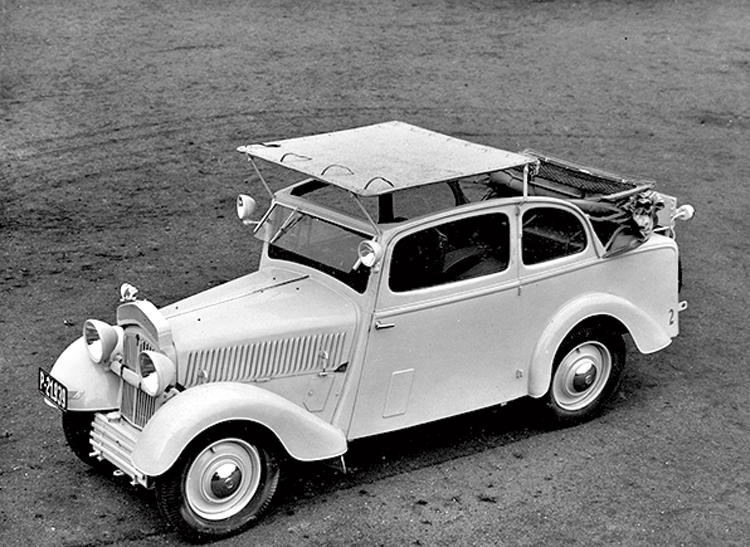

The expedition of 1934 was sponsored by the Motor Club of the University Sport. The two-seater semi-convertibles had one-litre four-cylinder engines. The vehicles had soft-tops, canvas hoods that could be rolled over. In case passengers wanted a more airy ride, the canvas top could be folded. And in case the sun was too much, the car had another canvas top mounted to shade passengers from the harsh rays. The top-hinged windshield could be opened to let air into the cabin with wipers dropping down from above. The convertible doors opened to the right with split seats inside. The Škoda logo, a winged arrow, was perched on the hood with the spare tyre propped up at the rear.

The expedition that began from Prague moved to Budapest, then Belgrade, then Sofia, then Istanbul, and from there on to Angola and then Beirut, moving on to Damascus, Baghdad and then Tehran. Thereon, the Populars moved through Meshed, Zahedin, Quetta, Multan, Lahore, Meerut, Benaras and finally to Calcutta.

At Quetta, the group separated as members experienced “cabin fever” (the feeling of being angry and bored for being inside too long). Šebela and Nádherný set off for Afghanistan. The other three Populars headed for Calcutta, the vehicle on detour with the Moravian licence plate turned off; the plan was for all of them to eventually meet up in Bombay. Šebela and co-driver Jan Nádherný drove from Quetta to Kabul, Peshawar and then down to Meerut from where they headed straight to Bombay.

Once in Bombay, all four Populars along with the motorists were loaded on to a ship to be taken to Trieste, the north Italian port. The vehicles then headed back to Czechoslovakia. By the time they arrived in Prague on September 10, 1934, they had covered nearly 15,000 kilometres, often over rough terrain and in harsh climatic conditions.

Apart from nature’s challenges in the form of difficult terrain, rocky stretches, deep mud, collapsed bridges and desert sandstorms, the crew faced some human obstacles as well. Bulgarian customs officials held them up thinking their thermos flasks were hand grenades. Hoffman managed to pass Turkish bureaucrats by giving them free medical treatment.

According to the glowing company release, the machines behaved “impeccably”. Apparently, the Šebela-Nádherný crew even decided to remove the additional cooler because even at high temperatures the standard design sufficed.

One of the vehicles being lifted to be ferried Photograph courtesy Škoda

There was one serious breakdown though, near Ankara in Turkey, when an atypical toothed wheel attached to the rear axle, especially designed for expeditions, snapped. An ordinary gear was installed thereafter and the Popular gave no more trouble for rest of the voyage.

Šebela’s presentation talks about that part of his journey when he leaves Afghanistan for British India. He writes, “The Khyber Pass at 2,100 metres must not be passed after 4pm. There is constant unrest there and no security was guaranteed. All the people we met had rifles.”

Šebela has written about the brand new asphalted road through Khyber Pass: “It is only for cars. For horses, donkeys and camels, the way is different, just rolled.” More jottings. He writes, “We have the first greeting from home in Peshawar. It’s a Bata subsidiary (a subsidiary company of Bata operating in Peshawar).” Bata is a Czech company. From Peshawar, Šebela and Nádherný travelled along the Kabul river to the confluence of the Indus river and entered undivided India.

More jottings. “We are now travelling through the Indian countryside. There is no empty road in India. On each kilometre we meet several people or carriages. Carriages are usually two-wheeled, very heavy. They are drawn exclusively by cows.” On their way from Lahore to Delhi, they note: “…lush greenery around the road, dense with a tree-lined avenue that protects travellers from the hot sun. Palm trees start to appear. Small grey squirrels run across the road. Monkeys run through trees by the road. Wild parrots and crows are walking above our heads. Wild peacocks flock majestically across the lawn.”

Of Delhi, he writes: “Old Delhi is an impure, busy city. All the life of the natives takes place in the streets, full of screams and noise. The business is concentrated in small shops, where the shopkeepers drag their customers together. They do it very tenaciously, with an obvious excess of temperament.”

One of the two-seater semi-convertibles with two canvas hoods Photograph courtesy Škoda

The duo experience the torrential tropical rain during the journey from Agra to Bombay. “Water was flowing across bridges in many places. It was not possible to use the bridges,” writes Šebela. He also observes cheekily, “It is a very clean nation. People often bathe and wash. They do their toilets at rivers. Here you see a native barber at work on the river bank. He shaves his customer’s chin. But Indian people shave also their heads, leaving only a strand of hair on top.”

Once in Bombay, they ended their land journey and boarded the Conte Verde, the ship that took them back to Europe. “Despite all the joy of returning to our homeland, every one of us felt a certain grief, a longing for this land with its myths and history of the rich Orient,” writes Šebela.

The Czech expedition was a matter of triumph for the seven adventurers. But above all it was the best advertisement possible for a machine at a time when advertisement was not quite the beast it is today. Was it effective? Apparently there is sound data to support that the number of Škoda vehicles exported to British India totalled 90 units per year in the second half of the 1930s. And in 1938, India ranked seventh among the Czech automobile manufacturer’s 39 export markets.

Now that’s what you would call one Popular campaign.