The four-storey structure is tucked in a lane at Kankurgachi in northeastern Calcutta. On top of the imposing iron gate is a logo; it shows a pair of hands, folded.

In one corner of a hall near the entrance, a man in a white robe is addressing a group of women. His talk is peppered with words such as qayamat, momin, ras, nabi; it sounds like a mix of Gujarati, Hindi, Arabic and Persian. From time to time, he reads from a text, explains the nuances in Hindi. The women, heads covered with pallus, listen with rapt attention.

Still deeper inside the space is a larger hall and at its centre, in an inner chamber, is a raised platform covered with a blue, heavily embellished cloth. On either side of the platform are garlanded pictures, but occupying pride of place is a book. Two jewelled crowns adorn it.

The Kuljam Swaroop, as it is known, constitutes 18,758 verses. The name is a derivative of the Hindi kul meaning complete and jam or depository. The text is considered the ultimate source of divine love and wisdom by those who frequent this temple — the Krishna Pranami Mandir of the Pranamis. Among the devotees that day there is a woman with her infant son.

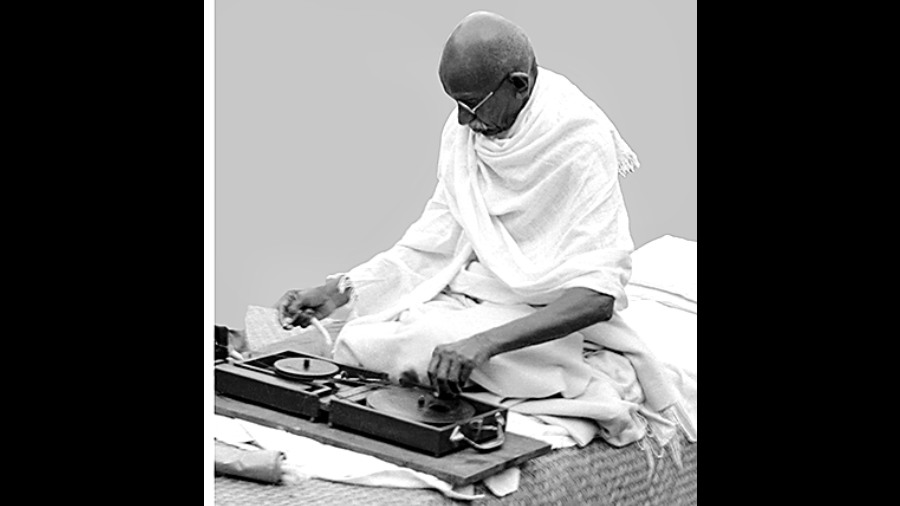

Two hundred years ago, 2,400 kilometres from Calcutta in Gujarat’s Porbandar, a mother and son would visit the temple behind their home. The 32-year-old woman was Putlibai, wife of Karamchand Gandhi who was the diwan of the princely state of Porbandar, and the six-year-old in tow was Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi.

“Just like Gandhi, the worldly-wise Putlibai was also strongly religious and fasted frequently. The Pranami sect (of Hindus) to which her parents belonged was said to bear an Islamic influence and did not worship idols. But Putlibai seemed comfortable with the Krishna, Rama and Shiva images honoured by the Gandhis; and she respected Jain monks,” says Rajmohan Gandhi, historian and grandson of the Mahatma, in an email to The Telegraph.

Rajmohan says the Gandhi household of the 1880s frequently received Muslim guests. “Respect for, and acceptance of, people of different religions seemed to be the norm; we can find in this the influence of Putlibai’s Pranami background — inherited from her parents.”

That his mother’s influence shaped Gandhi’s belief is evident in his autobiography. He wrote: “My family was Pranami. Even though we are Hindu by birth, in our temple, the priest used to read from the Muslim Koran and the Hindu Gita — moving from one to the other as if it mattered not which book was being read, as long as God was being worshipped.”

The Pranami Sampraday was founded by Devchandraji Maharaj when Akbar was trying to expand his empire using policies that tried to build bridges between the Hindu subjects and the Muslim ruling class. Devchandraji’s main disciple Mahamati Prannathji further consolidated the foundation of the sect during the reign of Aurangzeb.

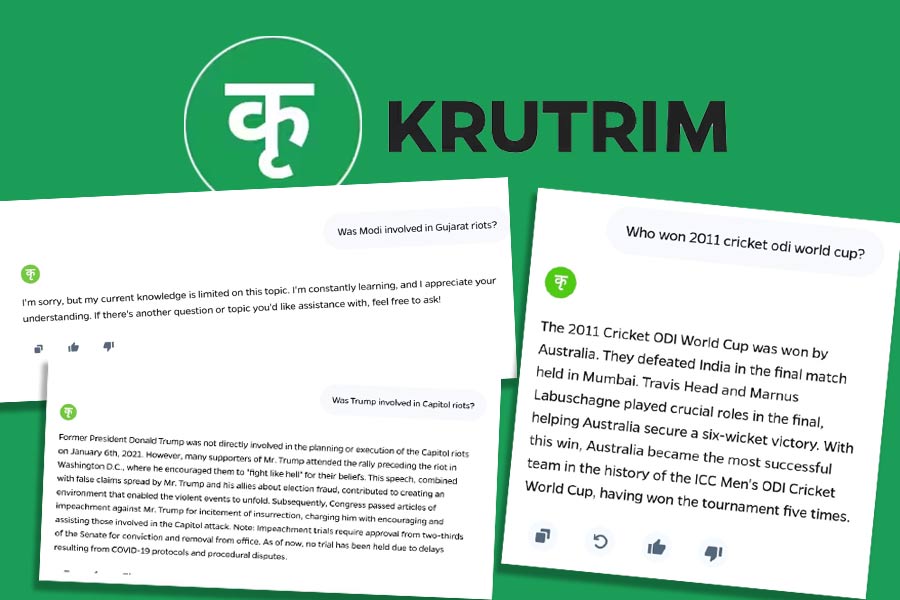

Gandhi’s secularism was a synthesis of various faiths and sects and is totally different from the Western notion of secularism espoused by Nehru

As Guru Mohan Priyacharyaji of Mangaldham, a Pranami temple in Kalimpong, north Bengal, tells it, Devchandraji was born in 1581 in Sindh (now in Pakistan) into a family of traders. He renounced the world to seek Brahma-gyan or knowledge of the Supreme God and settled down in Gujarat’s Jamnagar. His followers were called Nijanandas, a self-awakening sect. The sect’s philosophy of Hindu-Muslim harmony is reflected in a couplet: Jo kachu kahya Ved ne, so hi kahya kitaab/Donon bandey ek Sahib ke, par larhat paya bina bhed... What is said in the Vedas, is also said in the Book (Quran)/Both are children of the same God, but quarrel without knowing the truth.

Mahamati Prannathji had travelled to Oman, Iran and Iraq, and his teachings, including his Guru’s Tartam Sagar, were turned into the scripture Kuljam Swaroop, which is a synthesis of wisdom from the Vedas, Bhagavad Gita, Quran, Bible and Torah. The sect honours various religious sentiments, including prohibition of alcohol, non-vegetarian food and tobacco.

One of Prannathji’s initial disciples was King Chhatrasal of Panna of Bundelkhand, Madhya Pradesh. Gradually the sect found followers in Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Haryana, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Nepal and West Bengal. “Today, nearly a crore Pranamis have built hundreds of temples across the world”, says Navin Bansal, a businessman and also trustee of the temple in Calcutta.

Former culture secretary of the Government of India, Jawhar Sircar, known for his scholarship in religion, history and Hindu cults, compares the Pranamis with Gaudiya Vaishnavs, the followers of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu. According to him, Gandhi’s adoption of the syncretic philosophy of the Pranamis gelled perfectly with his politics. “Gandhi’s secularism grew out of the basic tenets of Hinduism which is flexible and inclusive in itself,” he says. “He realised that one can’t shake off religion from politics, which is deeply embedded as an Indian’s dharma.” According to Sircar, Gandhi’s secularism was a synthesis of various faiths and sects and is totally different from the Western notion of secularism espoused by Nehru.

Chavi Bhargava Sharma, a Delhi-based clinical psychologist, interviewed Pranamis between 1998 and 2006 for Wiscomp, a peace foundation of the Dalai Lama. She visited Pranami temples in north and west India. Her findings were published in a paper “Between Two Worlds”.

Sharma says, “This non-violent sect suffered a lot in 1947. Many of them were brutally killed in a planned attack, especially those based in Bahawalpur and western Punjab, now in Pakistan. They invited the wrath of fundamentalists of both faiths who wanted a clear demarcation of people on the basis of religion.”

The trauma inflicted during the Partition riots forced the Pranamis to migrate to India and shift towards a mono-religious identity. Sharma says that is when they added the prefix “Krishna” to the name of their community. Such deep wounds won’t heal easily while contemporary politics is leading to further denial and numbing of the pluralistic tendencies within our culture and traditions, she adds.

Bansal is a proud Pranami. All trustees who help manage the affairs of the Calcutta temple are devout followers of Guru Swami Sadanandji from Bhiwani, who focuses on altruism and philanthropy of Pranamis through Apna Ghar ashrams — residentials to care for destitutes in many cities.

In the last 75 years, the Pranamis have moved on. Rajmohan Gandhi knows of them as a distinctive community of Gujarat, but he is not sure if their customs and beliefs are similar to what the Pranamis of Putlibai’s times practised and believed.

Beneath the glass painting of Devachandraji and Prannathji near the sanctum sanctorum of the Pranami temple in Kankurgachi, there’s a Hindi inscription. It says: Serve through love and kindness to end all sufferings of the world.