He was there when Bob Dylan stunned the music world and played electric guitar at the hallowed precincts of the Newport Folk Festival. He was tour manager for The Band and helped build a studio for Messrs Robbie Robertson and Co. at Woodstock at a funky house called Big Pink. It was at his home that George Harrison ideated the historic Concert for Bangladesh. Then he got into movies and started off by producing one of Martin Scorsese’s early gems, Mean Streets. He went on to executive produce The Last Waltz, the seminal concert film that marked the closure of The Band’s touring days.

A Princeton alumnus, he has also studied Big Tech in detail, having had an early brush with the world wide web when he launched the Internet’s first video-on-demand service in the 90s. He has been professor at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism from 2013 to 2016. He is a member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, and currently sits on the boards of the Authors Guild, the Americana Music Association, and Los Angeles mayor Eric Garcetti’s Technology and innovation Council. He is now director emeritus of the USC Annenberg Innovation Lab.

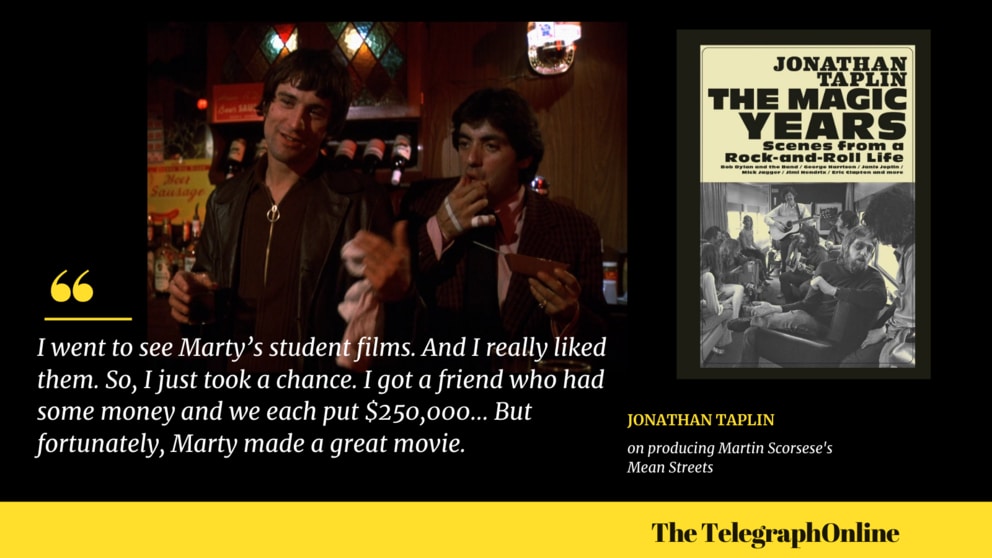

Meet Jonathan Taplin, a technology watcher _ “Move Fast and Break Things”, his first book _ music and film buff, who was in his early years delightfully naïve, and hence didn’t think twice about putting his own money in the movie business. He is all heart when it comes to making life choices. At the moment he is on a virtual roll, talking about his new book that chronicles his life, marked by luck, good timing and impeccable instincts. “The Magic Years, Scenes from a Rock-and-Roll Life”, published by Heyday Books, is described as both a “rock memoir” _ he rubbed shoulders with the likes of Jerry Garcia, Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton and many other icons _ and a cultural critique underlining key moments that tries to explain the modern world’s tumultuous trajectory.

Music, movies and Big Tech. I caught up with Taplin, a “three-in-one” walking, talking encyclopaedia and keen observer of popular culture, over Zoom and ferreted out priceless nuggets about George Harrison, Bob Dylan and his time with The Band, Martin Scorsese, and above all, try and get a sense of art’s power to jolt us out of “passionless detachment” and resurrect our innate “humanism”.

TTOnline: Let me start by asking you about George Harrison and the Concert for Bangladesh, the mega event organised to raise funds to help millions of refugees that were fleeing a war-ravaged country in 1971. I believe the idea was discussed at your home?

George Harrison had come to New York to make the record (late 1968), All Things Must Pass. And he was making it with Phil Spector. On weekends sometimes, he would come up to Woodstock to visit Bob Dylan, Robbie Robertson and The Band. And sometimes, he would stay at my house and sometimes he would stay at Bob’s house.

This was when you were with The Band, working as a tour manager?

Yes. Later, I met George in 1969 when we had gone to do the Isle of Wight (music festival, Newport, England) and he had invited me to his house. And I had stayed with him and Patty (Boyd) for a couple of days after that. One night in the spring of 1971, he said, ‘Ravi Shankar says that there is a complete crisis going on in East Pakistan. And nobody is aware, what’s going on’. And Ravi said, ‘We have to help these people. We have to get money in there ’cause people _ and a lot of children _ are literally dying everyday of starvation’. So, George being George said, ‘Okay, let’s do it.’ He said, ‘How do we do this?’ And I said, ‘Let’s do it in the biggest place we can get’, which is Madison Square Garden. Because we have to make as much money as we can. And I said we could probably do two shows in one day, and you could fill all 17,000 seats twice. And at a decent ticket price, you could make some real money.

What happened after that?

The next day, we all went down to Allen Klein’s office, who was the Beatles manager at the time, and booked Madison Square Garden for two nights; the last day of July we would use to set up the stage, sound system and do a sound check; and then Sunday, the first day of August, would be the two shows.

How was the band put together?

George just got on the phone and started calling people. And not a single person he called turned him down. We got Ringo (Starr) and Klaus Voorman (bass player and Beatles’ friend from Germany), Jim Keltner to be a second drummer, Leon Russel to play piano and Billy Preston to play organ. So that was the basic band. And Eric Clapton was going to be the lead guitar player. So, that came together fairly quickly. And then he got Bob Dylan. And then it just became something very real. It was remarkably fast in the way that it came together. I think we announced that it was going to happen in late June. And the concert happened in August.

Amazing. We are now observing 50 years of the liberation of Bangladesh. That concert, we saw the film much later in Calcutta, became the template of future benefit concerts.

Yeah. It accomplished two things, one of which was that it did actually raise awareness. Nobody (in the western world) had ever heard of Bangladesh before that concert. And afterwards, everybody, including politicians knew about Bangladesh. It raised at the beginning, maybe half a million dollars. Then, there was the question of how we could get that money to the people. And eventually, it was decided that we would just give it to Unicef. Once the record came out and then the DVD, the video of the movie and the video of the making of the movie, I think it probably raised 20 or 30 million dollars for Unicef over the years. So, it accomplished two things: it raised a lot of money and raised awareness. And raising awareness was at the time even more important than raising the money.

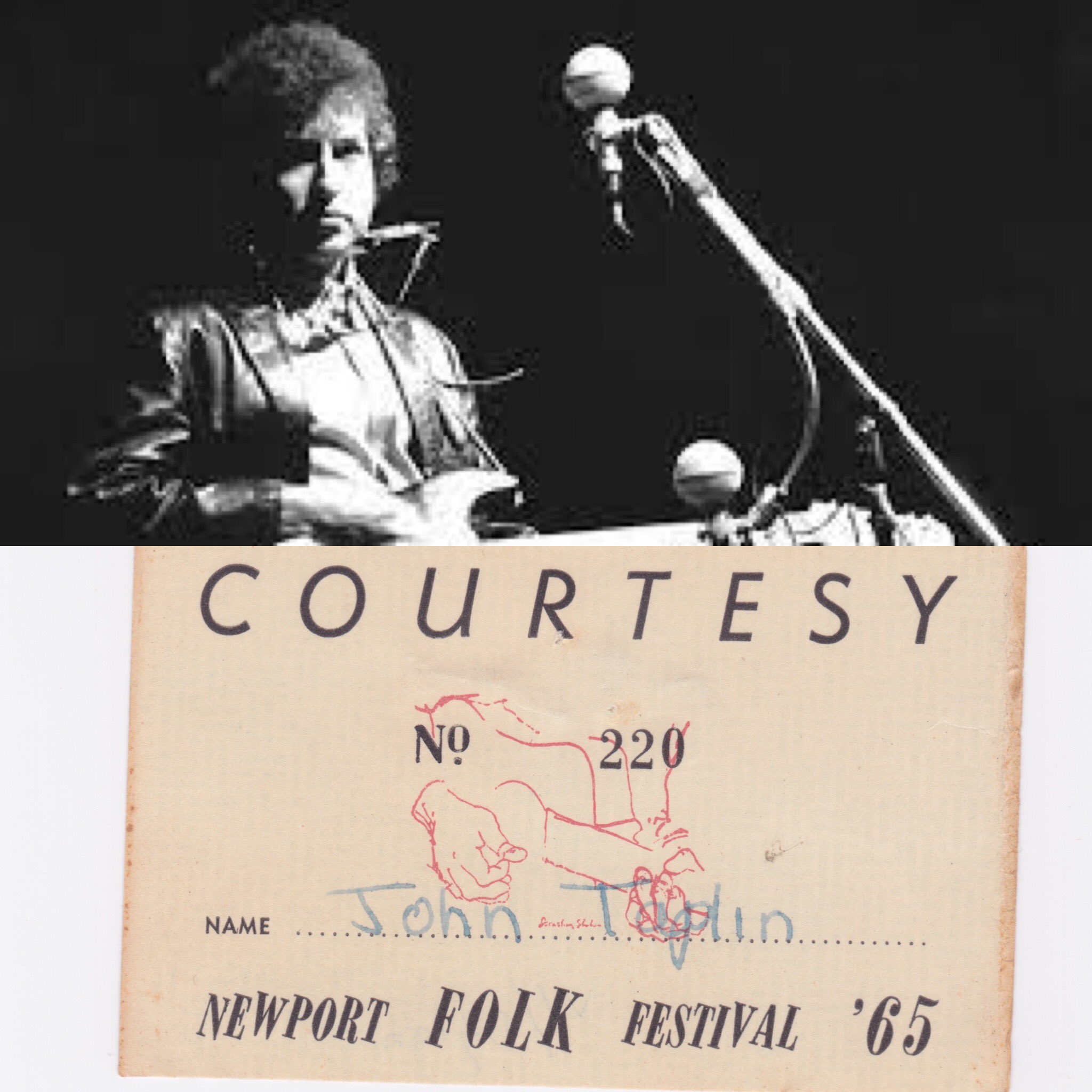

Now, about your early-life stint as a road manager for Albert Grossman, who was manager for Bob Dylan and a host of other bands of the 60s. You were there when Dylan went electric at the Newport Folk Festival?

Yes. The Newport Folk Festival was a kind of hallowed ground for folk music which was this “sacred” thing. And there were lots of people like Pete Seeger and Alan Lomax whose job was to protect this tradition and try and make this music available to a lot of people. Somehow Grossman got a band called the Paul Butterfield Blues Band invited to the festival. Grossman was managing Paul Butterfield too. And Butterfield played a workshop in the afternoon at the same time that Lomax was doing a country-blues workshop. And Lomax really objected to the whole thing and tried to literally unplug the electricity. And Grossman got into a fight with him (Butterfield). I was with a guy named Geoff Muldaur who was a singer in the Jim Kweskin Jug Band who was also managed by Grossman. We went back to the artistes’ tent and Muldaur told everybody the story of this fight between the old guard Alan Lomax and the new wave Paul Butterfield, and Dylan listened to it. And I am just speculating now that Dylan told himself, ‘Screw it. If that’s going to be their attitude, well, I am going to play rock and roll too. He already had a record on the radio at that time, Like A Rolling Stone, and so, it wasn’t that he had never played rock before. He had played it for a while, but he had never played it on stage. So they kind of very quickly assembled a band with Mike Bloomfield who’d played on Like A Rolling Stone and The Butterfield Blues Band rhythm section and Al Cooper who was an organ player. They just put it together very quickly, and it was pretty rough. But that’s how it came to be. But people booed and rejected it outright.

Memorabilia Twitter/ Jonathan Taplin

You write in your book that prior to Newport, Dylan had spent time with the Beatles. And you seem to suggest a Beatles connection to that epochal moment (July 1965) at Newport.

Bob did a tour of England in the spring of 1964. Bob was staying at the Savoy Hotel in London and he and John Lennon used to hang out every night. I think Dylan was introducing John to smoking hashish and also took other intoxicants. They were exchanging songs. And if you think about that, the distance from say, I Want to Hold Your Hand and to Nowhere Man on Revolver, is only about 16 months. But I would argue that Lennon being exposed to Dylan’s work changed him a lot. And in the same way, it also changed Dylan to see the fun that the Beatles were having playing rock. He wanted some of that fun too. I mean, everything had been so serious (till then).

You say you are speculating, but I think that’s exactly what one would expect Dylan to say and do _ you want me to do something? I won’t. I will only do what I want to do.

Right, exactly (laughs)

Now The Band years. You went on to be their manager and saw them working closely. Could The Band be the best example of one in the true sense of the term _ when musicians come together and create something that is way greater than the sum of their individual parts?

Yeah, I think so. I think maybe John Lennon could have had a solo career as a musician, and certainly Paul McCartney, and may be even George (Harrison). It’s probably hard to imagine that any one of The Band members could have had a solo career by themselves. But when they all got together, something magical happened. It really worked. And also makes me think about the very nature of being in a band. It’s very hard, right? I mean one of the themes of my book is that it’s hard to keep a band together. The Beatles survived for a certain number of years, but then it came apart because of personalities. And certainly, the Eagles had the same problem. But it happened to The Band as well. At some point it began to wear everybody out.

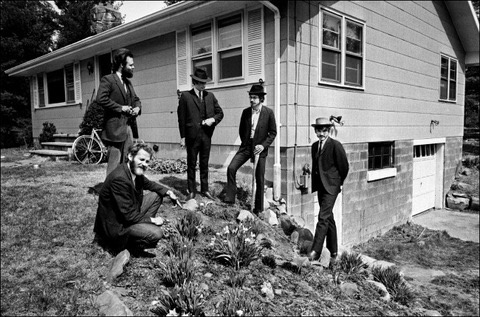

The Band in front of Big Pink, 1967 Twitter/ Jonathan Taplin

You describe The Band’s music as a “synthesis of folk music’s lyricism and rock music’s power”. Take me through the emotions you felt when Robbie Robertson and Levon Helm played The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down for you for the first time.

I’ve grown up in a kind of liberal background in America and I had been involved in the civil rights movement from 1963. In that sense, the notion of the White southerner was very much to me a problematic character in American history. And then, I came back from college and headed out to California where we set up this recording studio for The Band to make their second album. And they brought me down to this studio and played me The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down. And it was a very emotional feeling. In other words, I was kind of overwhelmed by it. And for the very first time in my life, I had a sense of the wounded pride of that character in that song. In other words, it was able to make me rethink what I was thinking about the role of the poor White person in the South. I thought it was a really powerful experience. I was crying at the end of the song. I mean it moved me very deeply. And it made me able to rethink things. It certainly helped me understand Levon a lot better who was from Arkansas from the deep South. I got a sense of his people. His father was a dirt farmer, very poor. All of The Band had kind of struggled out of rural parts. Rick Danko’s father chopped wood for a living. So, I mean, the song was about Levon in a sense, but it was all about any kind of poor working class person and the struggles they go through.

What did The Band bring to Dylan’s music? When The Band plays his songs, with or without him singing, the songs seem to acquire a larger than life perspective. What is intimate becomes emphatically universal. Case in point: When I Paint My Masterpiece.

The Band and Bob Dylan had a period, which we now call the Basement Tapes, in which they were completely out of the spotlight. Bob was recovering from a motorcycle accident. The Band was just kind of up there in Woodstock. They were still known as The Hawks and they just started experimenting with music. It started out as a way for Bob to put down some new songs that he’d written so his music publisher could send out a tape to other musicians who might want to record those songs. It wasn’t really meant for anything except as like a demo tape.

So out of that time, which was months and months, using a little two-track recorder that Garth (Hudson) had set up in the basement of this little funky house called Big Pink, they began to create a different kind of music. Now, we call it Americana. It’s actually a genre. But the idea of Americana didn’t exist then. For Bob, it was the return to some kind of folk roots that he had left behind. For The Band it was like an education in a kind of old-time music of America that came out of folk and bluegrass and these other traditions that they hadn’t really been aware of. They were really a rock and roll band, right? And they were very aware of Elvis and Carl Perkins and Muddy Waters and Sonny Boy Williamson. But they weren’t really aware of that other kind of Carter Family, Johnny Cash kind of world. So that was a very interesting thing. And out of that songs like Paint My Masterpiece came. And then Robbie kind of took some of that internally and he wrote The Weight which is very much in that same tradition. So, I think the combination of The Band and Bob was really amazing.

I had the opportunity to interview Richard Alderson who was the sound engineer when Bob Dylan toured with The Band in 1965-66, the time they were booed all over.

Yes, in the earlier times you speak of, they provided Bob a kind of spirited way of playing rock and roll music and marrying it with the poetry that he had always written. It was quite remarkable. Yes, they got booed around the world, but a few years later in 1969, when Bob and The Band came back to the Isle of Wight to play, they played the very same music that they’d played in 1966 and got booed at, and everybody loved it. Time had healed the wounds. I don’t know what had happened, but it was totally changed. And then in 1974 they played it, did a tour all over the United States and it was the same thing, people just loved it.

You were there when all this happened. Did you for once stop to think, and realise may be, that this was something special?

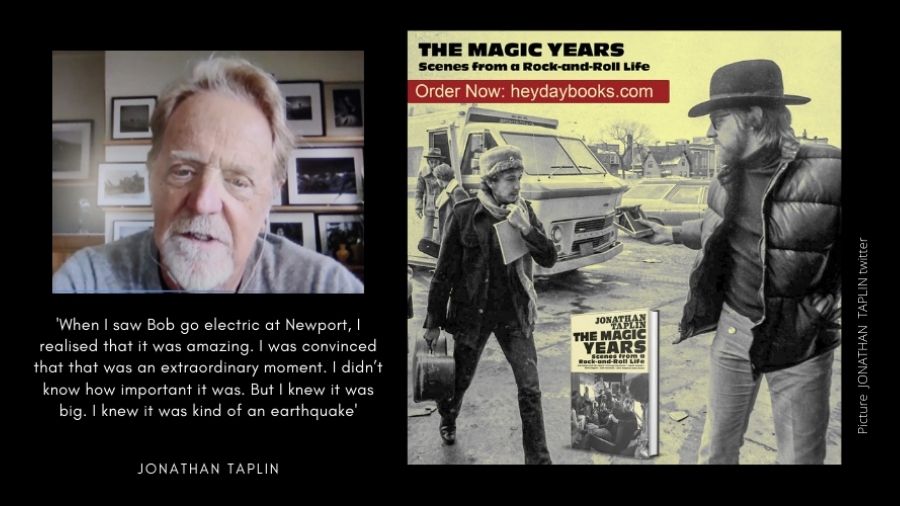

Yeah, I did. When I saw Bob go electric at Newport, I realised that it was amazing. I was convinced that that was an extraordinary moment. But I didn’t understand the import of it in the larger scheme of things _ which is that something major had happened to break between rock and roll and folk music. I didn’t know how important it was. But I knew it was big. I knew it was kind of an earthquake.

And Woodstock? You talk of it as a ‘Biblical experience’.

It could be that in India people experience a sight of 350,000 people in one place for some festival. But in the United States, we never saw that. So, when we came over this hill in this helicopter and you saw this gigantic crowd it felt like a Cecil B. DeMille movie. It was pretty dramatic. I had never seen anything like that and I haven’t seen anything like that since.

Tell me about your experience as producer of The Last Waltz. Does it hurt that not everyone in The Band was very fond of the film?

Look, Levon later on kind of got angry about the fact Robbie was doing better than he was financially. And that is strictly a factor of Robbie having written a lot of the songs. In fact, he wrote a majority of the songs that The Band performed. And after 2000, when Napster came out, the value of the actual master recordings, i.e., what the musicians would get from selling records, went way down. But songwriters continued to get paid because they had these collective performing rights organisations, BMI and ASCAP, which ensured that if a store is playing music in the store it has to pay some money to the songwriter. If a bar is playing music in that bar, it has to pay money to the songwriters’ organisation. So, songwriters kept getting/collecting money, and the musicians who played on the record didn’t get anything. This got Levon very pissed off.

But, I mean, the honest truth was that Levon didn’t write any song. And so, he then kind of took a view that the whole thing, The Last Waltz, was only there to make Robbie look good, and that Robbie and Marty (Scorsese) were in a kind of conspiracy to push Robbie forward. I don’t think it was true. And by the way, those interview segments in which Levon talks about the South and everything actually got Levon acting gigs in Coal Miner’s Daughter and The Right Stuff and all sorts of things. I mean, he benefitted as well. But you know, 2020 hindsight, it’s hard and sad. I am sad that Levon was angry. But I think The Last Waltz holds up. I looked at it recently, and it’s very good. And almost every single musician who played on it, played at the top of their game in that film. I mean Van Morrison is just amazing. Muddy Waters is amazing.

Yes absolutely. For many of us, it was an education. It opened up our world to music and musicians of a very high order. Scorsese directed Last Waltz, but you got to know him much earlier when you produced his film Mean Streets.

By late 1972, I was just kind of tired of the whole thing. I had done Concert for Bangladesh and that had been successful. Then we’d done Rock of Ages, which was a very successful live recording for The Band. And so, I went out to California. And Jay Cox, who had written a cover story on The Band for Time, told me, ‘When you get there, look up a kid named Martin Scorsese. He edited Woodstock and he’s a total rock and roll fan. And you guys will like each other as you have a lot in common’.

So, I got to LA and got in touch with him, and he came over to visit me at my house in Laurel Canyon. He brought a script with him called, ‘Season of the Witch’, that he’d been trying to get made for three or four years unsuccessfully. And I was so naïve, I didn’t know you weren’t supposed to put your own money into movies! In Hollywood they have a phrase, ‘OPM’ or ‘other people’s money’. But I didn’t know that phrase. I went to see Marty’s student films. And I really liked them. So, I just took a chance. I got a friend who had some money and we each put $250,000 which was basically all the money I had in the world. And we took a chance. Again, it was a complete naïve, and probably stupid, move. But fortunately, Marty made a great movie. And we were able to sell it to Warner Brothers and we got our money back.

You’re a very brave person.

Brave or stupid?

Well, you seem to follow your heart.

Yes. I always follow my heart. Sometimes the heart takes you to places that you realise are not so great. And sometimes, you’re in places that are just amazing and wonderful. But the main thing is not being afraid of change.

So how was the journey of putting this book together?

It took me about a year once I started working on it seriously.

How do you remember so much? Did you maintain a journal?

I have a very good memory (laughs). In fact, I remember more from the 60s and 70s than I do from 5 weeks ago (laughs).

That’s wonderful, because you know what they say, ‘If you remember anything about the 60s, you weren’t there.’

Bursts out laughing.

Thank you for talking to The TelegraphOnline, and congratulations on your book.

Thank you. It was lovely talking to you.