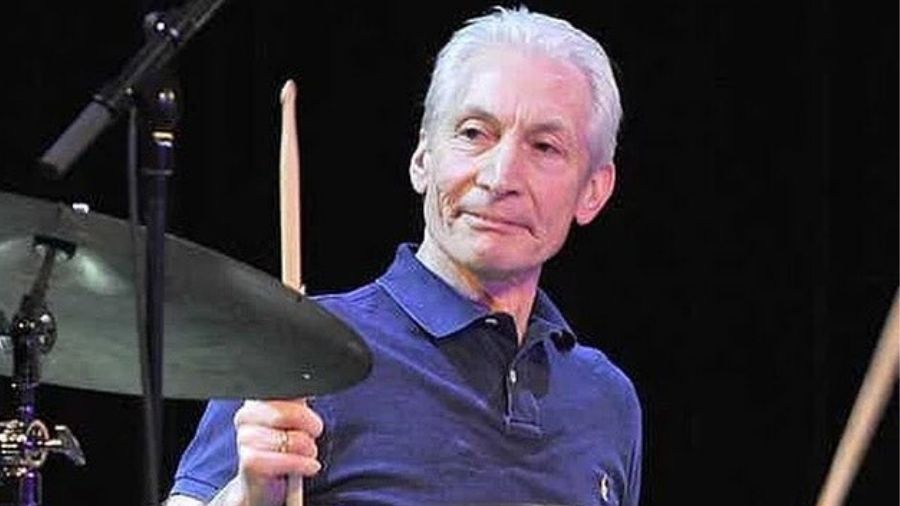

On some superficial level, Charlie Watts had always seemed the oddest Rolling Stone, the one who never quite fit as a member of rock’s most Dionysian force.

While his bandmates cultivated an attitude of debauched insouciance, Watts, the band’s drummer since 1963, kept a quiet, even glum, public persona. He avoided the limelight, wore bespoke suits from Savile Row tailors and remained married to the same woman for more than 50 years.

Watts even seemed barely interested in rock ’n’ roll itself. He claimed that it had little influence on him, preferring — and long championing — the jazz heritage of Charlie Parker, Buddy Rich and Max Roach. “I never liked Elvis until I met Keith Richards,” Watts told Mojo, a British music magazine, in 1994. “The only rock ’n’ roll player I ever liked when I was young was Fats Domino.”

Even the Stones’ celebrated longevity represented less of a life’s mission to Watts than a tedious job punctuated by brief moments of excitement. In the 1989 documentary “25x5: The Continuing Adventures of the Rolling Stones,” he summed up what was then a quarter-century on the clock with one of the world’s greatest rock ’n’ roll bands: “Work five years, and 20 years hanging around.”

And yet Watts, who died Tuesday at 80 as the Stones’ longest-serving member outside of Richards and Mick Jagger, was a vital part of the band’s sound, with a rhythmic approach that was as much a part of the Stones’ musical fingerprint as Richards’ sharp-edged guitar or Jagger’s sneering vocals.

“To me, Charlie Watts was the secret essence of the whole thing,” Richards wrote in his 2010 memoir, “Life.”

Watts’ backbeat gave early hits like “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” a steady testosterone drive, and later tracks like “Tumbling Dice” and “Beast of Burden” a languid strut.

His distinctive drumming style — playing with a minimum of motion, often slightly behind the beat — gave the group’s sound a barely perceptible but inimitable rhythmic drag. Bill Wyman, the Stones’ longtime bassist, described that as a byproduct of the group’s unusual chemistry. While in most rock bands the guitarist follows the lead of the drummer, the Stones flipped that relationship — Richards, the guitarist, led the attack, with Watts (and all others) following along.

“It’s probably a matter of personality,” Wyman was quoted as saying in Victor Bockris’ book “Keith Richards: The Biography.” “Keith is a very confident and stubborn player. Immediately you’ve got something like a hundredth-of-a-second delay between the guitar and Charlie’s lovely drumming, and that will change the sound completely. That’s why people find it hard to copy us.”

Watts’ technique involved idiosyncratic use of the hi-hat, the sandwiched cymbals that rock drummers usually whomp with metronomic regularity. Watts tended to pull his right hand away on the upbeat, giving his left a clear path to the snare drum — lending the beat a strong but slightly off-kilter momentum.

Even Watts was not sure where he picked up that quirk. He may have gotten it from his friend Jim Keltner, one of rock’s most well-travelled studio drummers. But the move became a Watts signature, and musicians marvelled at his hi-hat choreography. “It’ll give you a heart arrhythmia if you look at it,” Richards wrote.

To Watts, it was just an efficient way to land a hard hit on the snare.

“I was never conscious I did it,” he said in a 2018 video interview. “I think the reason I did it is to get the handout of the way to do a bigger backbeat.”

Watts’ musical style could be traced to mid-1950s London, the period just before rock took hold among the post-war generation that would dominate pop music a decade later. As a young man he was infatuated with jazz, often jamming with a bass-playing neighbour, Dave Green. In 1962, after stints in local jazz bands, he was recruited by guitarist Alexis Korner to join his group Blues Incorporated, which was influenced by electric Chicago blues and R&B.

“I went into rhythm and blues,” Watts recalled in a 2012 interview in The New Yorker. “When they asked me to play, I didn’t know what it was. I thought it meant Charlie Parker, played slow.”

While Watts was in Blues Incorporated, Jagger, Richards and Brian Jones — the other founding guitar player of the Rolling Stones — all passed through, playing with the group. Watts joined the Stones at the start of 1963, and that June the band released its first single, a cover of Chuck Berry’s “Come On.”

The Stones quickly took their place as leaders in rock’s British Invasion, the rowdy complement to the Beatles. But Watts never quite matched that profile. On the band’s early tours of the United States, he behaved like a middle-aged tourist, making pilgrimages to jazz clubs.

As the lifestyle of the Rolling Stones became more extravagant, Watts grew more solitary and eccentric. He became an expert in Georgian silver; he collected vintage cars but never learned to drive. Journalist Stanley Booth, in his book “The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones,” about the glory and the depravity of the band’s 1969 U.S. tour, described Watts as “the world’s politest man.”

At the same time, Watts often functioned as a kind of ironic mascot for the band. He was a focal point on the covers of “Between the Buttons” (1967) and “Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out!” (1970), on which a smiling, leaping Watts posed with a donkey.

When members of the Stones relocated to France in 1971 to escape onerous British tax rates, Richards’ rented villa in Villefranche-sur-Mer became the band’s hub of creativity and decadence. Watts and Wyman largely abstained, and as a result were absent for some of the ad hoc recording sessions that resulted in the band’s next album, “Exile on Main St.”

“They weren’t very debauched for me,” Watts later said of the sessions. “I mean, I lived with Keith, but I used to sit and play and then I’d go to bed.”

While around the Rolling Stones, he was invariably laconic, usually lingering in the background during public appearances. But later in life, as Watts indulged his love for jazz in the long stretches between Stones projects — his groups included the Charlie Watts Orchestra and two with Green, the Charlie Watts Quintet and the ABC&D of Boogie Woogie — he opened up, giving occasional interviews.

His go-to subjects were his love of jazz and how strange it was to be a member of the Rolling Stones.

“I used to play with loads of bands, and the Stones were just another one,” he told The Observer, a British newspaper, in 2000. “I thought they’d last three months, then a year, then three years, then I stopped counting.”

New York Times News Service