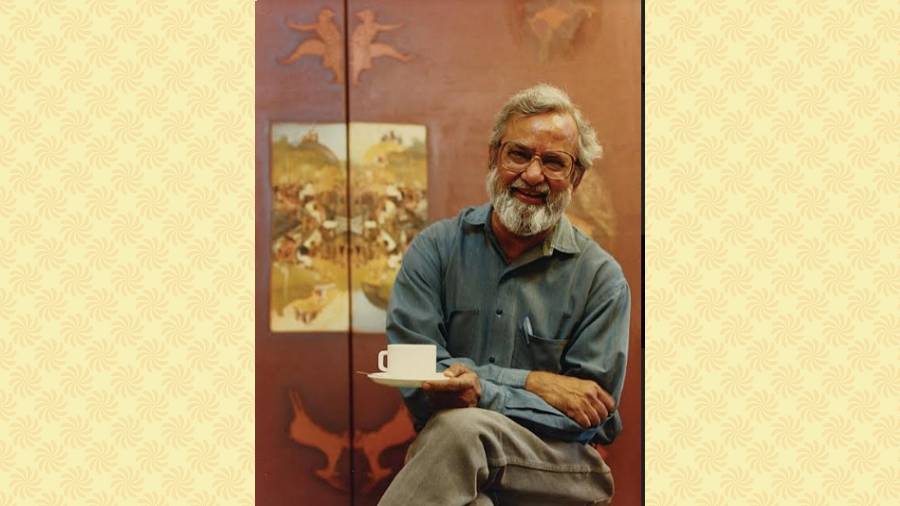

Gulammohammed Sheikh turns 85 this month. He was born on February 16, 1937, into a middle-class Sunni Muslim family in Surendranagar, a small, laidback Saurashtra town in Gujarat.

When he was 15, he started a handwritten magazine titled Pragati with friend and mentor Labhshankar Rawal. Another friend, Shantilal Shah, introduced him to the art wealth of Jain temples. Sheikh, thus, grew up amidst a syncretic camaraderie. He once recalled in an interview that in the mornings he would recite from the Quran at the madrasa and in the afternoon he read Sanskrit scriptures from the Upanishads and Kalidas. The Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb, which later coloured most of his works, emanated from Surendranagar.

Sheikh joined the faculty of fine arts at The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda in 1955. Baroda (now Vadodara), known as the cultural capital of Gujarat, embraced him with open arms. Doyens of the Indian art world N.S. Bendre, Sankho Chaudhuri and K.G. Subramanyan taught him. Sheikh’s interest in

Gujarati poetry and world literature also grew here in the company of litterateur Suresh Joshi. Sheikh contributed to Joshi’s little magazines and also started his own magazine Vrishchik with artist friend Bhupen Khakhar.

In 1961, M.F. Husain opened Sheikh’s first solo exhibition at the Jehangir Art Gallery in Bombay (now Mumbai). Till then, most of his work was figurative and derived from his childhood memories of whinnying horses and tongas.

Sheikh was part of Group 1890, formed in Delhi by 12 artists. They held their first and only group show at New Delhi in 1963, which was opened by Jawaharlal Nehru. Mexican poet Octavio Paz, who stopped by, appreciated the show and remarked on the “deliberate absence of ideological meaning”.

That year Sheikh received the Commonwealth Scholarship to study at the Royal College of Art, London. During his time there, he travelled extensively through Europe taking in artworks by the masters as well as contemporary European artists.

On his way back to Bombay, Sheikh decided to travel by land wherever possible. Journeying through France, Italy, Greece, Turkey, Iraq, Athens, Istanbul, Sarajevo, Aleppo and Baghdad, he got a sense of various civilisations, their people, history and world art.

On returning to India he resumed teaching at Baroda. In 1971, he married Nilima Dhanda, who went on to become a famous painter in her own right.

City for sale, housed at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, UK, is one of the most ambitious paintings by Sheikh. It depicts polarisation and communal violence in Baroda in the early 1980s. Sheikh continued to paint it for about three years against the backdrop of continuous violence in the city. In his words, “I began to develop a superstition that every time I picked up a brush a riot would begin.”

This was not the first time Sheikh picked up a brush to paint the realities around him. His 1972 painting Road 2 (Vietnam) was inspired by the photograph known the world over as The Napalm Girl. Speechless City was painted during the Emergency years.

The Tree of Life mural at Bhopal’s Vidhan Bhavan is indisputably one of the most important projects in Sheikh’s career. He created a tree of wisdom on an epic scale. Despite the fact that it was commissioned by the Madhya Pradesh government, he did not refrain from depicting the Union Carbide catastrophe in the mural.

I was first introduced to his work as a teenager by my father at art exhibitions. I happened to meet him for the first time at the launch of his Gujarati poetry collection Athawa Ane in 2013 in Mumbai. The poet Gulzar attended the event.

Sheikh has earned universal admiration and friendships. Even today, he doesn’t feel burdened by his popularity.

I have seen him sitting in the audience at a lecture by the critical theorist Homi K. Bhabha and asking questions like a true seeker.

The Gujarat riots of 2002 shook the artist. Paintings such as Alphabet Stories represent how each letter of the Gujarati alphabet lost its original meaning. Walled City found Gandhi in exile. Vadodara 2002 and Fort, Ahmedabad 2002 show fault lines and large blots on the maps of these cities. My personal favourite, Ahmedabad: The City Gandhi Left Behind (2016), illustrates the deliberate erasure of Gandhian heritage and values.

Sheikh’s affection for medieval saint Kabir is reflected in his works and life. He named his son Kabir. In 2019, I organised an event of Kabir songs by Shabnam Virmani at Vadodara. People didn’t show up for the event due to heavy rains and thunderstorms, but to our surprise Sheikh and Nilima made it.

I was talking to poet-friend Prabodh Parikh the other day and he admired Sheikh’s meticulous nature. He said, “He is so much like the Japanese. He should have been born one.” It reminds me of the evening when I was supposed to meet him at his studio to present him my poetry collection. I was five minutes late. When I reached, I saw him sitting upright in his chair waiting for me.

Sheikh has taught thousands of art students in his teaching career spanning more than three decades. He generously collaborated with younger artists.

Whenever I meet him or speak to him over phone, his zest for life and compassion inspires me to be a better person. I wish many more years of good health and creativity to Sheikh saheb.

The writer is a Gujarati poet and an award-winning filmmaker