All those years ago, the Mughals had kicked up a storm in this desert land. Rajputana — supposedly the fief of a valorous people — has been stormed yet again, this time by the gau army. Already, in Alwar, Rajasthan, its crazed foot soldiers have spilled blood a few times in the name of protecting the Mother. The marauding force, evidently, is not made up of vigilantes only. It consists of traders (and, certainly, politicians) as well. The vyaparis are making a fast buck too: cow urine is reportedly fetching a fortune. Can a Rajasthani neta then be faulted for suggesting that the key to ruling India is protecting the cow? (Never mind that in the process of cooking up the tale, he had imagined that Humayun was Babur’s father; history has never been the BJP’s strength.)

But there was a time when the camel — and not the cow — ruled Rajasthan’s heart. In fact, for Bengalis — the real and the not-so-real — Rajasthan was synonymous with the uut. Lalmohanbabu (aka Jatayu), that wondrous creation of Satyajit Ray, was the self-appointed cheerleader for the uut among Bengalis. Riding a camel, he says in a memorable sequence in Sonar Kella, was the stuff of his dreams as a child.

Every Bengali child shares Jatayu’s dream. My dream — uut-e chora — had, ironically, come true on a sandy stretch, not on the Thar but on the beach in Puri. On spotting a camel during a visit to the beach, I realised, much to my horror, that the child in me had somehow eclipsed my adult self. For I was drawn to that thoughtful ungulate like a moth to light while it sat facing the sea, its jaws munching on fodder, as if it was pining for the desert. The uut’s minder, realising that his pet had cast a spell on me, decided to make some quick money, much like the modern vyaparis peddling cow pee. A half an hour’s journey on the camel, he informed me, would cost me a fortune. I fell for the deal and climbed atop my dream (most loss-making ventures are owned by Bengalis, or so goes an urban legend).

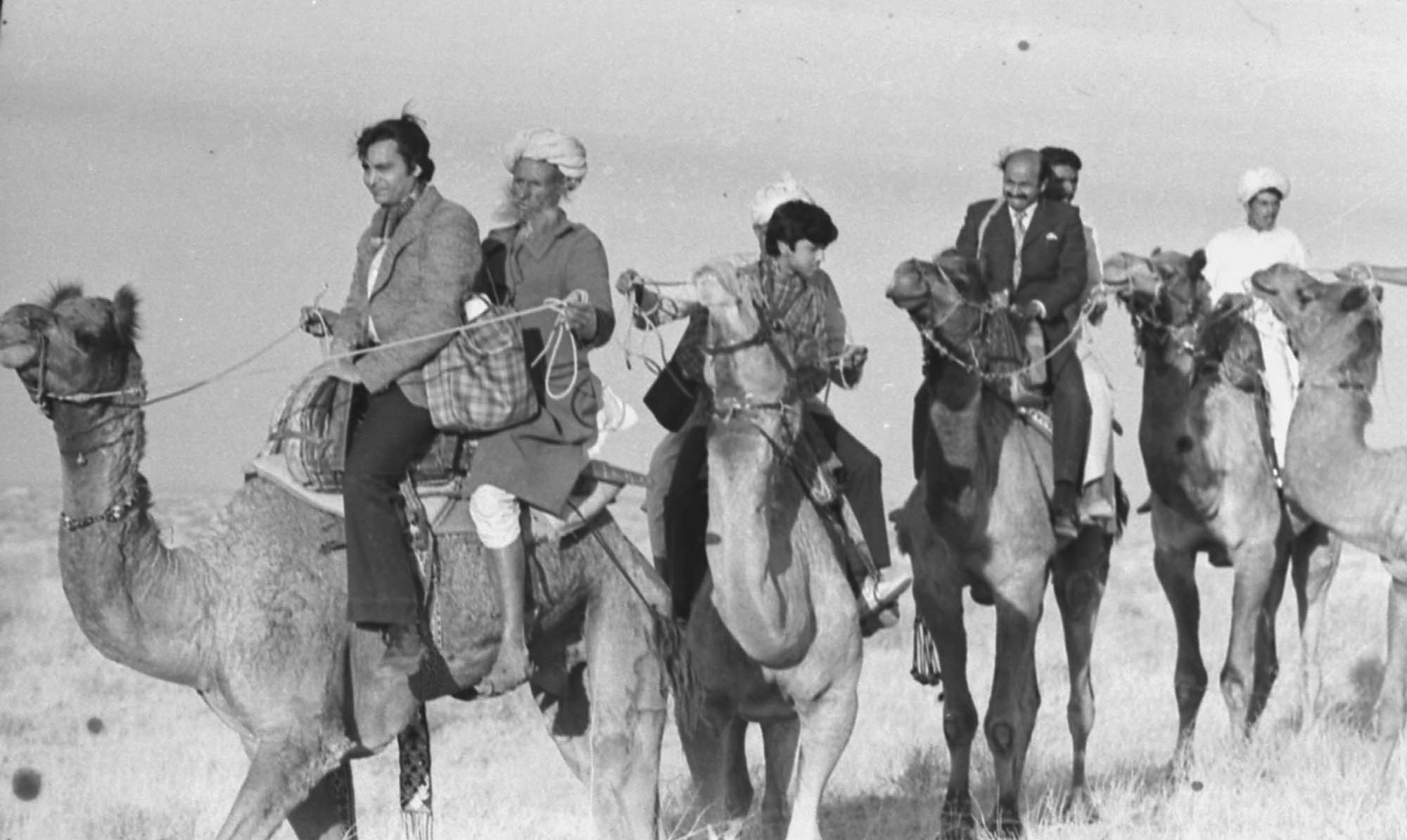

A still from Sonar Kella File image: The Telegraph

But then dreams, I learnt on the sands of Puri, are rather fragile entities. At a sign from the uutwala, the camel began to raise its posterior first, forcing me to perform, what in Bengali is known as, a ramhumri — a lurch forward at lightning speed (Jatayu, I remembered even as I was being hurtled forward, had suffered the same fate).

What he did not suffer was the reverse ramhumri — an equally forceful movement, but this time in the opposite direction. I happen to hold that dubious record. After raising its hind legs, the camel began to lift its front limbs and my body lurched backwards, as if I was travelling back in time.

So when I visited Rajasthan — Jodhpur and Jaisalmer — I kept a distance from my dream-turned-nightmare. One scorching afternoon, after I had finished scouting the old bazaar in Jodhpur, I stood waiting for an autorickshaw. None appeared. It was apparently siesta time after stuffing oneself with daal-baati-choorma. A cart-driver stopped and enquired whether I wanted a lift. The next moment, he saw me transform into The Flash. For I had spotted a camel tethered to the cart.

A few days later, I found myself inside Jaisalmer fort. Sonar Kella wasn’t quite glittering in the evening light. The edifice was crumbling; several kholis inside the fort had been rented out to foreigners, some of whom lay sprawled on hand-woven carpets inside the dingy, chillum-smoke-filled chambers; the drains were dry and covered with filth.

I had watched Mukul walking and, later, running to escape his abductor on reel. Now, I was following in Mukul’s footsteps, relishing the experience of the reel slowly giving way to the real.

An old guide stopped me on my stroll. “This is beautiful,” I told him, pointing to the golden stone walls that had been baked by a fierce sun that was now setting. “Beauty,” the guide said, “lies outside the walls of the fort.” He beckoned and I followed, reaching an open terrace.

“Look,” he pointed into the distance. Following his finger, I saw a nomad family walking with some camels. They were Banjaras, headed towards a new grazing ground possibly. The men, women, children and camels — all of them were family — were silhouetted by the orange orb on the horizon.

Watching the distant figures recede, I realised that some dreams, including the ones featuring uuts, are indestructible. In other words, ramhumri-proof.