Book: Explaining Life Through Evolution

Author: Prosanta Chakrabarty

Publisher: Allen Lane

Price: ₹599

Prosanta Chakrabarty’s book is also about the nuts and bolts of evolution. The primary subject, though, is the stark difference between the theory and its reception and political use. Chakrabarty has spent most of his working life in the US, the scientific superpower whose people have doggedly refused to get science at all, from the Scopes ‘monkey trial’ of 1925, which concerned the teaching of Darwinism, to the present legal threat to the right to abortion.

Chakrabarty’s account begins in Louisiana in 2008 with Bobby Jindal backing the teaching of biblical scripture in schools as an alternative to evolutionary theory. It ends with Narendra Modi’s talk of stem-cell technology and plastic surgery in the epic age. The local news is even scarier: the BJP MP and former military doctor, D.P. Vats, has told Parliament that ‘partial eugenics’ — screening embryos for genetic disorders — would be good for the nation. But who would define the disorders? Chakrabarty legitimately wonders how a party obsessed with spurious notions of purity would use the CRISPR gene editing suite.

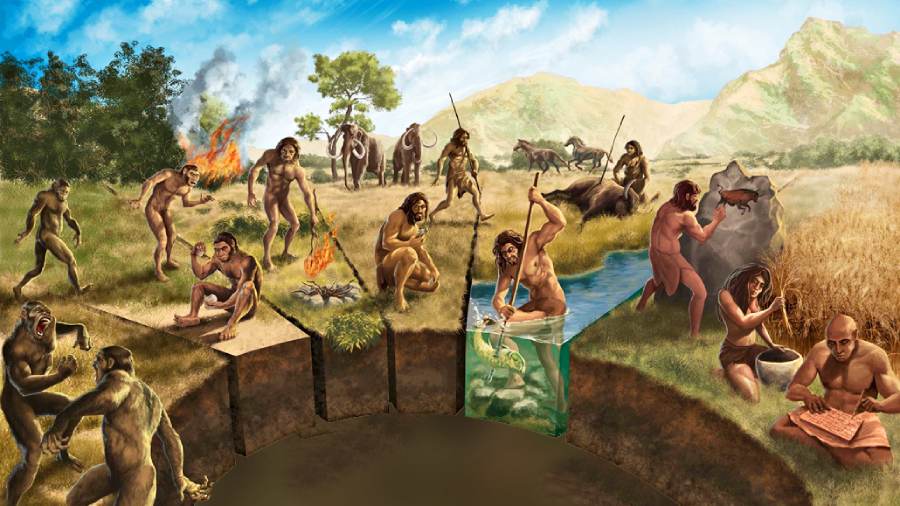

Evolutionary theory is misused because it is misunderstood. The most dangerous misunderstanding is attributed to Darwin himself. The layperson reads ‘fittest’ in Darwin’s ‘survival of the fittest’ theory to mean the most deserving or most eminent rather than the most successful procreator. That misreading helps maintain order in the ranks, keeping Brahmins on top and Dalits way below, for instance. In England, Darwinism pulled the rug from under the Great Chain of Being that the Elizabethans loved, stretching from Caliban up to the angels, while paradoxically, its misreading seemed to validate the hierarchy.

Anti-evolutionists scoff at the idea that humans are descended from monkeys (hence, ‘monkey trials’), which the evolutionists never claimed. The theory posits a remote common ancestor, but that’s too nuanced for identity politics. It must be misunderstood in order to be weaponised, and thereafter, debunking is useless. For instance, Chakrabarty mentions blue eyes in passing, part of the iconography of Aryan supremacist theory, which seeks pure origins. After his book went to press, the mutation which causes blue eyes was found to have occurred only 6,00010,000 years ago, a fraction of the hundreds of thousands of years of human cultural prehistory. The believers are unaffected.

Why does anti-science fly so readily, whether in Bobby Jindal’s bailiwick or in Narendra Modi’s, or among anti-vaxxers? Chakrabarty attributes it to the undermining of trust in science. The layperson cannot possibly understand gravity waves or neurotransmission and must believe experts. Experts, too, must trust each other, because the canon of science and math has grown exponentially and consists of specialists working in verticals of knowledge. But the web of trust is easily broken by right-wing political operators who have a simpler portmanteau explanation for everything: ‘Trust me, I know what you want.’

Chakrabarty takes the trust problem very seriously, but strangely he says nothing about the staggering betrayal of trust in the pandemic years in which he finished writing the book. When facing extreme health threats, the world looks to WHO and Western scientific institutions for protocols. This time, they cautiously relied on lessons from the flu pandemic of a century ago and prescribed personal sanitation barriers, which were later found to be irrelevant. If the importance of masks is taken lightly, it’s partly because of the hand sanitiser debacle — after creating a global industry and changing human behaviour everywhere, researchers found that fomites don’t matter. A loss of trust followed, and one would have expected it to figure prominently in Chakrabarty’s book.

With Covid becoming endemic and monkeypox in the offing, viruses should have got much more attention. They could have been the first life forms, strands of genetic material adrift in primeval seas, unprotected by a cell wall — a preconscious Solaris. Chakrabarty misses the opportunity, but he tells us that kangaroos have three vaginas. That’s a scoop that only a life scientist could have brought us. Siddhartha Mukherjee, a doctor, profiled the gene in a much more literary book, but for such extraordinary trivia, one must depend on the biologist.