Every regime seeks to create its own history and narrative. Sometimes, these are built not by acts of creation, but by those of erasure — of events past and future. We are living through times when the State has been manufacturing such acts at an accelerated pace — by renaming places/streets, demolishing iconic and heritage buildings, or manipulating school curriculum. History and public memory are thus being erased to make way for a mythical one.

Devika Sethi’s book delves into similar trappings of “preventive” and “punitive” erasure, charting the history of censorship since the turn of the 20th century. Unlike other texts, this book, rather than making analytical points on the nature and acts of censorship (which are more easily remembered), presents to us the words and ideas themselves (some long forgotten or vanished).

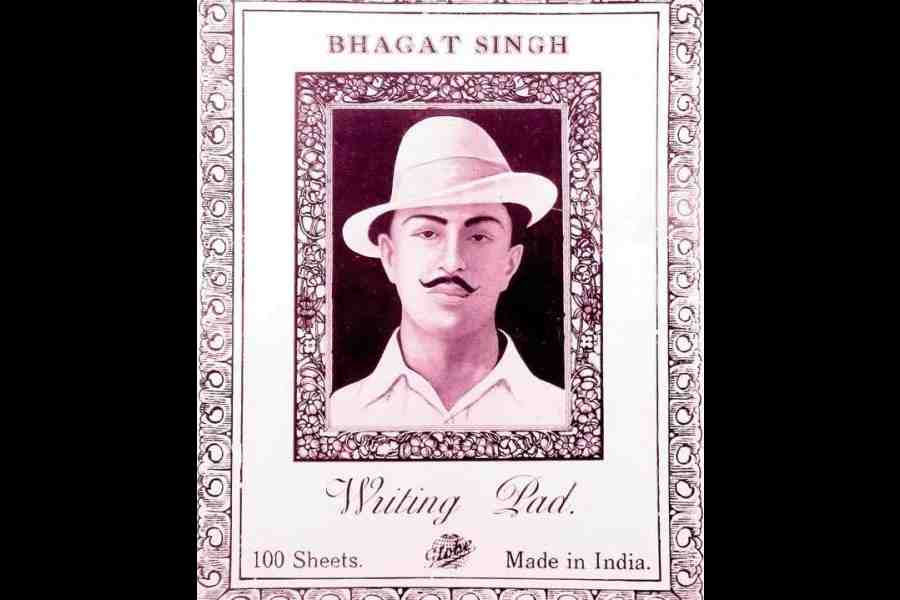

Sethi maps the period from 1900-1947 when literary, critical and political thoughts were intertwined, spanning decadal shifts. Key historical events and movements, such as the Bengal partition of 1905, swadeshi, boycott of foreign goods, political assassinations, executions, Jallianwala Bagh, Non-cooperation, Civil Disobedience, operate as landmarks, charting the rise and fall of figures familiar to us from history books, along with some lesser-known voices, covering the political spectrum from Left to Right. We are left to choose what we want to do with or think of them.

Living in the age of social media and instant news bytes, it can be quite difficult to comprehend where we would be shorn of the ease with which the internet and technology bring the world at our fingertips. One would expect significant setbacks a century ago when correspondences would only happen via print media, postage or telegrams. Sethi makes it clear, however, that this never deterred the urgency and the swiftness with which leaders and revolutionaries exchanged ideas and organised movements, often at great personal risks.

Communist thought came to India at around the same time it did globally, in the 1920s. Large networks of Indians supporting the anti-colonial movement abroad ensured global political thought and events were reflected in vernacular literature, sometimes even smuggling ‘seditious’ writings across borders. The tone shifts 1930s onwards, with “Indians’ ardent desire for communal amity, racial and class equality, and a steely determination to shape their own future.”

India’s censorship and terrorism laws are living relics from the colonial period, having been added to, not replaced. Over the last decade, the list of political prisoners and martyrs has only grown longer. Assessed diachronically, the timing is ripe for the contents of this book to find a larger resonance today. A significant number of these texts were penned within jail walls and one cannot help but think of the political prisoners who remain largely forgotten in contemporary times. Maybe a few decades from now, their correspondences from within will make it to another such book charting the history of these times.

The book also stands as a reminder that despotic governments behave the same way across time and space, operating on false dichotomies of Us and Them that are assumed to have homogeneous identities. The sheer heterogeneity of the pieces reproduced in this book is enough to dismantle that assumption.

While some of the poems/songs “embedded in… popular culture” still speak out to us in protest spaces, we are left to wonder why today’s socio-political events and injustices fail to galvanise people in a similar fashion, leading us to question the structures present today which inhibit a greater revolutionary response. The contents of this book could fan and feed the imagination of the current generation looking for inspiration for or blueprints of their own movements.