The daughter of two friends of mine lives alone, like me, in this city. But she’s only sixteen. She arrived three years ago with her father, her stepmother, and a stepbrother much younger than she is. The father is a painter and had a big fellowship at an academy up on the hill. I’d met them at one of his exhibits. The painter and his wife used to come to my place for Italian lessons. The daughter never joined them. She attended a high school nearby, and two years later she decided not to return to her country of origin, to separate early from her family and stay on here. She has a room in an apartment the high school oversees, a special residence to house students in her situation.

I call her when there’s an exhibit I want to see, or when the sales begin at the end of winter and the start of summer. I’d promised my friends I’d keep an eye on her, even though this girl doesn’t need very much from me.

I watch her as she cycles through the piazza. She could be my daughter given that I’m thirty years older. But she’s already a woman, with a beauty that’s disarming. A girl who smiles as she speaks, as if to declare to the world, See how happy I am. Nothing like I was at that age: still a child, no boyfriends, ill at ease. I’m envious. I still regret my squandered youth, the absence of rebellion.

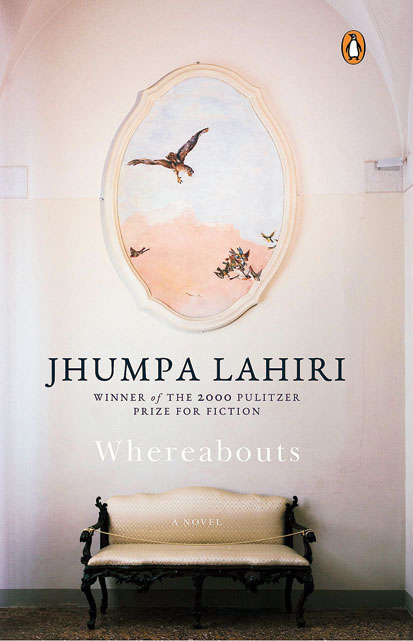

Whereabouts releases on May 27. Hamish Hamilton

She’s just come back after spending a week with her family. She’s relieved to have put some distance between them again. She tells me that spending seven days in a row together is rough: that her father and stepmother are always bickering and that they should separate.

“Don’t they love each other?”

“I doubt it. My dad just wants to paint and she’s at loose ends, she waits on him hand and foot and it drives him crazy.”

“And your mother? Did you see her?”

“She got married again, to a guy I don’t like.”

She drinks a glass of pomegranate juice. It looks like a glass of blood, though I don’t tell her that. She says she’s hungry and asks for a cornetto. She splits it in half, then divides one of the pieces. She takes a small bite, then arranges the rest of the pieces on her napkin.

People turn to look at her as we’re sitting in the piazza but she doesn’t pay them heed. She’s fluent in the language her parents struggled to speak. She doesn’t look like a tourist or foreigner, she’s the type that fits in anywhere.

The parents are worried, they’re hoping she’ll change her mind and decide to go to a university that’s closer to home. I don’t tell them, when we speak on the phone, that they’ve already lost her.

Full of dreams and plans, she believes it’s still possible to change the world. She’s already brave enough to stand up to authority and she’s determined to make a life for herself here. I’m fond of this girl, her grit inspires me. At the same time I think about myself back then and feel depressed. As she tells me about the boys that want to date her, amusing stories that make us both laugh, I can’t manage to erase a sense of ineptitude. I feel sad as I laugh; I didn’t know love at her age.

What did I do? I read books and studied. I listened to my parents and did what they asked me to. Even though, in the end, I never made them happy. I didn’t like myself, and something told me I’d end up alone.