Book: Until August

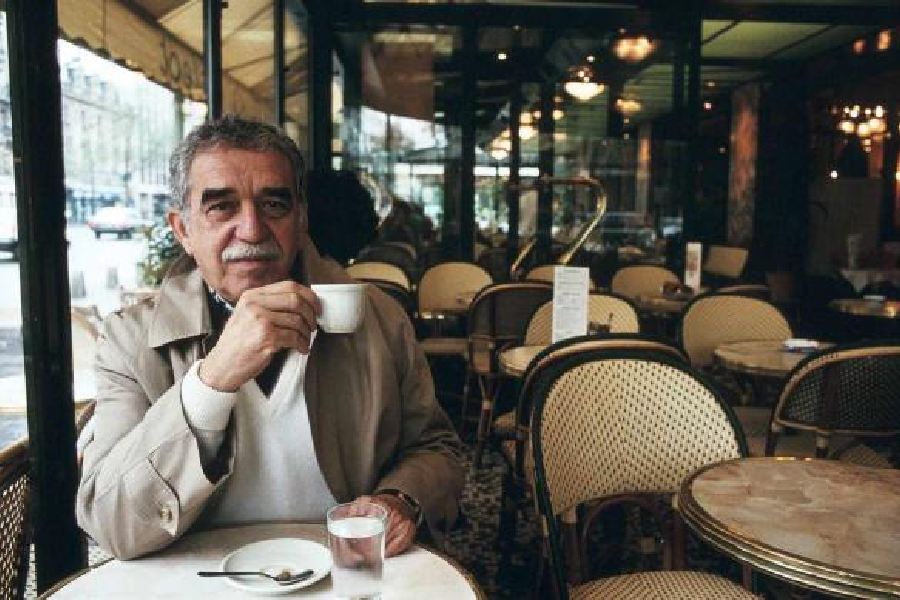

Author: Gabriel García Márquez

Published by: Viking

Price: Rs 799

Many years ago, on a rainy afternoon, when the ugly chaos of life threatened to engulf me, I was rescued by Úrsula Iguarán Buendía. The celebrated matriarch of One Hundred Years of Solitude is as formidable as she is powerless to stop those around her from making mistakes that affect her entire family. Yet, the fortitude with which she endures repeated losses — she watches five generations of the Buendías die — and tragedies was moving, illuminating and encouraging, all at once.

Many years later, on a hot summer afternoon, when I cracked open Until August — probably the last novel (although novella is a more apt description) by Gabriel García Márquez — I met Ana Magdalena Bach. It was a meeting laced with guilt — was it a betrayal of Márquez to read a work he wanted destroyed? — trepidation — would it live up to the magic that Gabo unfailingly spun throughout his career? — and, undeniably, excitement at the gift of a new work from the master of magic realism.

In Until August, Ana Magdalena Bach is a shadow of the female characters that Márquez has fleshed out. On August 12 each year, Bach makes a pilgrimage to a cemetery on an island off Colombia’s shore to clean her mother’s grave and fill her in on family gossip. This brief escapade also gives her some respite from her husband, a domineering musician, and their grown children, each of whose characters seems more unidimensional than the other. Bach, a teacher in her late forties, is forever conscious of her fading but still clearly visible beauty — the author’s undisguised male gaze in her portrayal is bound to both surprise and disappoint those familiar with Márquez’s oeuvre. On one such trip, Bach rediscovers her libido and goes to bed with a man who leaves $20 between the pages of her book the next morning. Part horrified and part fascinated by this experience, one-night stands with a series of men become integral to this annual ritual. Some of Bach’s self-assessments give readers glimpses of the Márquez of old — in the exploration of the transactional nature of desire, the exposition of how closely a woman’s sense of self-worth is linked to her sexuality, and the ignominy of ageing and what it does to a once-striking woman. Each encounter leaves Bach lonelier and more disillusioned.

Her own infidelity wakes Bach up to signs which reveal that her husband has been adulterous all along. But the interactions between the couple that follow leave readers yearning to reach for his earlier works. Márquez’s touching portrayals of familiarity, resentment and love, the latter almost a habit between couples who have been married for a long time, are unforgettable: think of the time when Fermina Daza and Doctor Juvenal Urbino do not speak for weeks after arguing about a bar of soap in Love in the Time of Cholera; it is a disagreement that is packed with therancour of a thousand marital obstinacies and slights. The passion which that couple could summon over soap, this couple cannot over serial adultery.

The setting of the novel, though, still has the flourish of a writer who has portrayed his beloved Columbia like few others have. The poverty of the “destitute village, with its mud-walled shacks, [and] palm-thatch roofs” is instantly recognisable. Progress arrives on the island in the form of hotels like “precipice[s] of gold-tinted glass” but fails to touch the lives of destitute islanders whose grimy existence becomes a sharp foil for the so-called development. However, what is most frustrating is the absence of the linguistic flamboyance and wizardry with words that Márquez himself took such pride in — he was a perfectionist and revised his novels meticulously, rewriting them over and over again. The Autumn of the Patriarch, for instance, took him 17 years to finish. If one assumes that Anne McLean has been faithful and adept with the translation — and there are bits of prose that suggest that she has — then the repetitive passages — “She did not hesitate for an instant. And she was not wrong: it was an unforgettable night. Much less forgettable than Ana Magdalena Bach could have imagined” — seem like a travesty coming from Márquez.

But books do not exist in a vacuum, they are products of the circumstances they are written in. Márquez’s sons, who published the book posthumously, claim that this work was a “race between [Márquez’s] artistic perfectionism and his vanishing mental faculties.” Indeed, Until August reads like an attempt by a once-brilliant mind to spin magic for one last time, with the spell weakening as the plot progresses. Should the manuscript then have been destroyed like its ailing and helpless author had requested it to be? No, that would have been too great a loss. But should it have been cobbled together as a novel from the various drafts of the work? Perhaps not. Could it be argued that a publication of the various drafts themselves along with images of the original manuscript — a few pages of which are reproduced at the end of this book — would have done greater service to Gabo by giving his readers a peek into his creative process?