Book: Flaming Forest, Wounded Valley: Stories From Bastar And Kashmir

Author: Freny Manecksha

Publisher: Speaking Tiger

Price: ₹599

Engaging analyses of two of India’s foremost restive regions — Jammu and Kashmir and Chhattisgarh — are not uncommon. Radha Kumar’s Paradise at War and Nandini Sundar’s The Burning Forest are two examples that come to mind. But what Freny Manecksha attempts here is both ambitious and important. In the course of her travels to these fractured lands, she chronicles, for the Mainland’s smug readership, the overlapping elements between these two theatres of conflict, an endeavour that is not quite common among the fraternity of researchers and journalists.

The reconstructions of the complex histories of the flaming forest and the wounded valley are adequate. What would be of particular interest to even seasoned commentators on Kashmir is Manecksha’s — albeit brief — examination of the contribution of the intellectual constituency to Kashmir’s dissent against the monarchy. “... [O]ne of the spaces for this political awakening came through the concept of a reading room, which then evolved into the Kashmir Reading Room Party that nurtured the nascent aspirations of leaders like Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah…”

The informed reader is also drawn to the dots that Manecksha joins in realms where a paranoid State seems to have turned against its own people. The stories of brutality, their unparalleledness notwithstanding, may be familiar. But the convergences demand attention because they point to continuities in the State’s militarisation policy. For instance, the ancestry of Chhattisgarh’s Salwa Judum and its depravity could well be traced back to Kashmir’s rogue Ikhwanis; the battle to save pastoral land in Kashmir would also be a reminder of the adivasi struggle for forested land in Chhattisgarh.

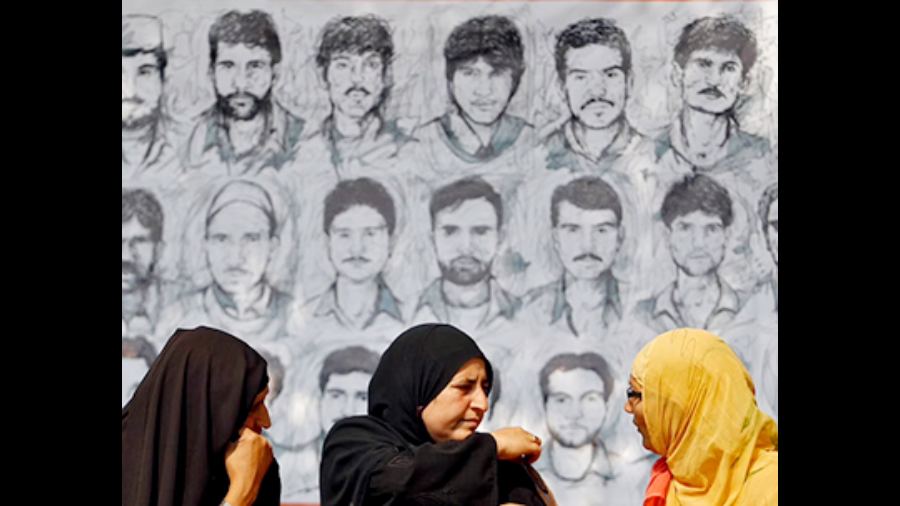

But more than the meta-narrative — of violence and violations, death and despair and also resistance and resilience — what enables Manecksha to force the gaze is her ability to tease out glimpses of the everydayness of life under siege. These intimate, atomised snippets function as the building blocks of the bigger, grim picture. Each nugget proffers a searing tale; and each tale is a tryst with injustice — adivasis conflating bodily violations with the rapacities inflicted upon jal, jangal and zameen; the only hotel in Dantewada turning guests out in the middle of the night if the police were on their trail; the ability of Kashmiris to weaponise grief; a young Kashmiri poet remembering the angry flames arising out of what was once his home; a woman waking up to the terror and humiliation of a torchlight being shone upon her countenance by the night patrol.

The Union home minister recently announced — triumphantly — the fading footprint of Maoists and of militancy. The agenda, of course, is to disseminate a sense of closure. But what this closure entails — the deep injuries inflicted by the State and its adversaries on life and land — needs to be investigated for the sake of accountability. Manecksha’s book is critical in this context.